NAKED OR NUDE (Kenneth Clark thought there was a difference), the human body has been a source of creative inspiration in all forms of visual art and performance, from painting and sculpture to theater, film, performance and body art, digital art, and live political activism. The public display of the nude body with its multiple and complex associations has a powerful impact on our awareness of the self and otherness. Recently, we have been experiencing an explosion of global protests in which activists have stripped themselves of clothing to draw attention to the vulnerability and power of the body in the social system we live in.

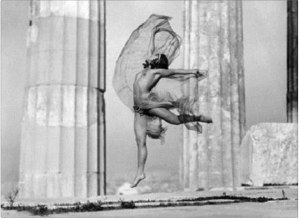

A protest precipitated by Greece’s financial crisis occurred in May 2013, in the center of Athens. “No God, No Master” was written across the chest of a blond woman from the “Femen” group, who posed in front of the Erechtheion Temple on the Acropolis as a Caryatid of modern times. This incident brings to mind Isadora Duncan photographed in the Parthenon by Edward Steichen in 1903, or Mona Paiva, dancer in the Opéra Comique, in Paris, who posed in the same place for the well-known Greek photographer Nelly in 1927, followed two years later by the Hungarian dancer Nikolska. The site of these incidents also reminds us that nudity has been an integral motif in the arts for thousands of years.

Beyond the boundaries of political activism, an explosion of nakedness has also been present in the performing arts and particularly in dance. In A Brief History of Nakedness, Philipp Carr-Gomm points out that “nakedness in ballet may still be rare, but when it comes to contemporary dance there have been many more naked performances in dance over the last fifty years than there have been in the theatre.” How can we interpret this increasing display of bare bodies in contemporary dance? By returning to the body, free from the symbolism of clothing and of moral codes, dancers and choreographers seem to be exploring a pre-cultural sense of being human.

And how do different audiences perceive the sense of intimacy that nudity attaches to performance? Although nudity can signify innocence or purity, it remains a controversial issue in the arts and in society at large. As Judith Lynne Hanna notes in her essay on sexuality in dance (2010): “Dance and sex both use the same instrument—namely, the human body—and both involve the language of the body’s orientation toward pleasure. Thus dance and sex may be conceived as inseparable even when sexual exploration is unintended.”

Nudity and Modern Dance

In an era still dominated by Victorian morals, Isadora Duncan dared to expose her breasts in some of her dances. Her idea of combining the body as flesh with a symbolic notion of the soul shifted the image of the female body away from eroticism. “What mattered in Isadora’s Hellenic dances,” explains Ann Daly (1995), “was not the Greek themes or the gauzy costumes but the uninhibited vitality, the sense of a glorious nakedness about to be affirmed, not only in the rituals of lovers but in every part of life.” Classical Greece had the power to “purify” taboos associated with the naked body as well as womanhood.

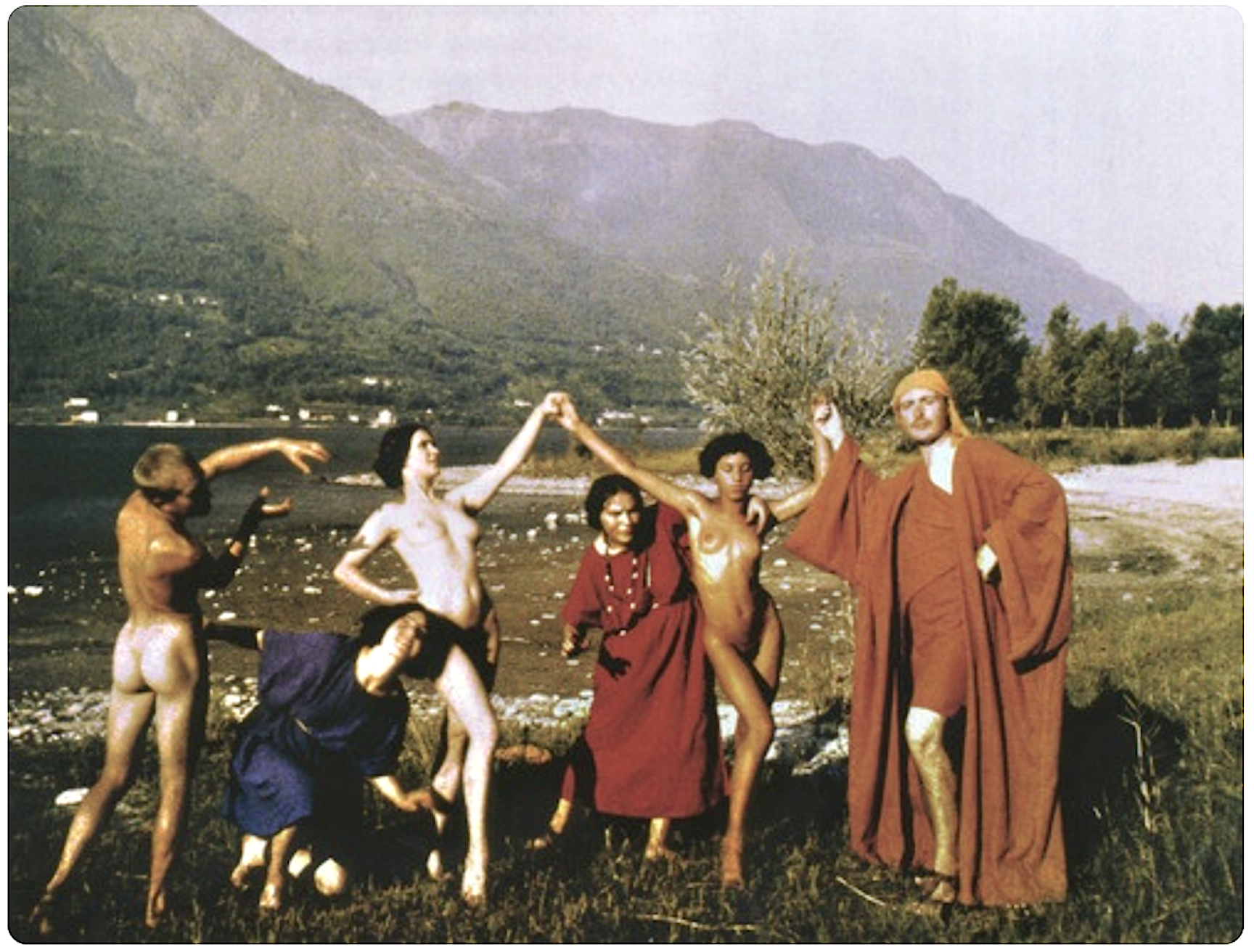

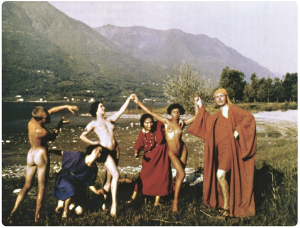

Expressionist dance pioneer Rudolf von Laban also explored the naked body as a site of liberation in the utopian society of Monte Verità in Ascona (1913-1918). Numerous paintings and photographs feature thousands of people naked in an ecstatic dance, anticipating the central position of the body to the creation of a modern, liberated identity. By the time the Dadaist and Surrealist movements exploded in Europe, Laban’s women dancers were performing quite frequently in the soirées of Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich.

The potential of the naked body to signify primal emotion played a major role in its fight against social and sexual conventions in German Expressionism and its dance offshoot, Ausdruckstanz. Although expressionist dance was denigrated by the Nazi regime as a degenerate art, the naked body was exploited as a tool of propaganda. Leni Riefenstahl in Olympia (1938), her documentary of the Berlin Olympics, includes footage of naked athletes, both male and female. They reveal her own appreciation of the human body, but they also illustrate the Nazi notion of the perfect Aryan body, associated with the classical Greek ideal of heroic beauty.

Photo: Johann Adam Massenbach

By the mid-20th century, Mary Wigman, Doris Humphrey, Martha Graham, and Merce Cunningham had developed virtuosity and formalism in their choreography, often using decorative sets and costumes. Despite the significance of their work in the development of modern dance, they were skeptical about the use of nudity. At a time when the entertainment industry had reduced the body to a fetish or a commodity, they sought to establish dance as a “noble” art form.

In the 1960s, the shift from modernism to postmodernism in the arts marked a return to the body—both in the physical and the performative sense. Amelia Jones (2000), art historian, critic, and curator, observed: “The body, which previously had to be veiled to conform to the Modernist regime of meaning and value, has more and more aggressively surfaced during this period as a locus of the self and the site where the public domain meets the private, where the social is negotiated, produced and made sense of.”

In 1965, Anna Halprin’s legendary piece Parades and Changes shook the dance world by challenging the traditional prohibition against nudity, as the dancers dressed and undressed onstage. When the piece was revived in 2009 at the Athens-Epidaurus Festival in Greece, no one complained about the nudity. But in 1967, at a performance in New York City, Halprin’s use of nudity on-stage caused her to be arrested by the police. In a recent interview, Halprin stated: “It was so radical when I first did it. [But] now nudity in dance is so ordinary. Sometimes I wish the dancers would put their clothes back on if they don’t have a good reason to be naked!” Despite Halprin’s arrest, naked dance was here to stay, and New York became one of the centers for this mode of expression, which spread out to the mainstream stage (think Hair, on Broadway, in 1968).

In 1970, Yvonne Rainer participated in “The People’s Flag Show,” an anti-war protest exhibition, with a version of her legendary Trio A (1966). The piece was performed by six nude dancers with American flags tied around their necks. Their bodies took advantage of the long association between nakedness with freedom. Other examples are Steve Paxton’s Satisfying Lover (1967), in which the simple act of walking became a kind of dance, stripped to its essentials, as well as Site (1964), which was created and performed by Robert Morris. While Morris manipulated several large wooden boards, Carolee Schneemann sat motionless onstage throughout the performance, recreating the image and the nude figure at the center of Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863).

Schneeman, a pioneer of performance art associated with both the Fluxus movement and Judson Dance Theater, is known for her shocking erotic performances and films. In The Interior Scroll (1975), she slowly extracted a paper scroll from her vagina and started reading it. The text, which was part poem, part manifesto, explained that she used her body (mythical or human) to examine female sensuality to achieve political and personal liberation from oppressive social and æsthetic conventions.

In the 1980s, the art world was deeply affected by the HIV epidemic and the repressive politics of the Reagan–Thatcher era. However, American choreographers continued to make political statements with reference to their identity—as female, as gay, as black—through nudity and dance. In Europe, Pina Bausch incorporated semi-nudity and cross-dressing for men in her renowned work for the Tanztheater Wuppertal, which was interpreted as a manifesto for a feminist æsthetic.

In the early 1990s, in the context of contemporary dance, particularly in Europe, there occurred a revival of interest in the body that could be traced back to the postmodern experiments of the 1960s. Writer and curator André Lepecki noted in his essay, “Skin, Body, and Presence in Contemporary European Choreography” (1999) that “The contemporary European dance scene can be qualified by one term: ‘reduction’—of expansiveness, of the spectacular, of the unessential. Accompanying this reduction in dance is a stripping of the dancing body itself. Naked bodies are ever more present on European stages.” By the end of the ’90s, audiences in Europe were witnessing the emergence of a new generation of choreographers whose work downplayed theatrics and brought them closer to performance art. New developments in European choreography could be found in some distinguished pieces by French choreographers Jérôme Bel and Boris Charmatz, German choreographer Felix Ruckert, and Portuguese choreographer Vera Mantero.

In 1994, Jérôme Bel presented his first piece, Nom donné par l’ auteur, in which two performers manipulated household objects, mostly in expressionless silence. His next piece, self-titled Jérôme Bel (1995), is a complete example of deconstructing “theatrics” through performative acts (including its famous urination on stage), self-referential speech acts, citations, and collage. Lepecki wrote this in his textual analysis of Jérôme Bel (1999): “No lighting design, no sound system, no costumes, no set. … This staging of bareness (preceding and echoing the bareness of the dancers) already sets up the scene for a critique of desire within our commodity-oriented culture.” What’s more, the bodies of the four dancers, one man and three women, “are not the ones that may be expected in a dance show. … They are ‘normal’ bodies, not slim, not lean, not muscled, not all within the prime of their youth.”

Challenging audiences’ views of normative images of the body cannot be separated from the accompanying shift in philosophical approaches to dance. The reading of texts by eminent thinkers of the mid-20th century became a source for the initiators of conceptual dance, who aligned this genre with philosophy in their choreographic texts, legitimizing the status of the choreographer as “author.”

The Bare Body in the 21st Century

Nearly two decades after the emergence of conceptual dance, it seems there’s a new wave of nudity in avant-garde dance performances. Gia Kourlas, in a 2006 review for The New York Times (February 12, 2006), claimed that in many recent performances the skin has practically taken the place of costume. In her view, this resurgence of nudity is not rooted in the sexual liberation of the 1960s or the political defiance of the 1980s. “Instead, choreographers are baring it all as a way to reveal something essential about human experience.”

In a provocative article titled “The Flesh Is Still Weak. So is the Mind,” Angela Conquet considers what a naked body can reveal that a clothed one cannot: “So what is it about nudity that provokes such moral panic, especially given the prevalence of (porno)graphic imagery within music and popular culture?” Comparing the use of nudity in the 1960s to its use today, she replies: “We have moved on from [the naked body’s]political militant use to a sort of ‘ground zero’ with respect to nudity [and are now]more concerned with a highly conceptualised un-gendered un-sexualised bareness, rather than political statement.”

Having seen many performances in which nudity is a dominant feature, we believe that it is not nakedness per se that causes moral concerns but instead what the naked bodies are doing, how they are framed, and how they challenge the spectators’ voyeuristic gaze. Whether they are engaged in sexually suggestive motions, whether this interaction involves opposite-sex or same-sex pairings, or indeed multiplicities—these are the kinds of questions that must be included in any discussion about the naked body and its difference from the clothed body.

In his production Tragédie (2012), Olivier Dubois set out to explore the human condition as inspired by Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. At the beginning of the performance, nine male and nine female dancers, all nude, emerge from darkness and walk up and down the stage for a half-hour. The audience has plenty of time to observe their individuality with their rich variety of body types, birthmarks, and tattoos. While the dancers remain naked throughout the performance, they unexpectedly appear clothed for the curtain call.

In 2014, for a presentation of Tragédie at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre, all major newspapers attended, and there was quite a lot of ink about the performance. The Daily Telegraph’s Mark Monahan noticed (May 9, 2014) that “the nakedness—which in contemporary dance is usually a sign of choreographic desperation—feels slightly less gratuitous than it might: the point, after all, is the shedding of socio-political shackles and rediscovering a common humanity.” The Independent’s Zoë Anderson (on May 9, 2014) ignored the nudity but disliked the boring choreography: “Tragédie deliberately follows classical models. It aims for catharsis by building from ordered pacing to wild flailing. The dancers walk for perhaps half an hour before allowing variation to creep in—a quirked elbow, a faster turn. They step into anguished poses, as if modeling for a bad painting.”

Unlike in Tragédie, the dancers in Alain Platel’s Out of Context—for Pina (2010) are never completely nude. The piece has strong intimations of the work of Pina Bausch, to whom it was dedicated. In this piece, Platel, who founded Les Ballets Contemporains de la Belgique in 1984, uses nine extremely virtuosic dancers.

At the beginning of the performance at the International Dance Festival of Kalamata, in Greece, the dancers were sitting among the audience. Then, one-by-one, they climbed onto the stage, stripped to their underwear, folded their clothes, put them on the ground, covered their bodies with large orange blankets, and just stood there waiting for their individual action-moments. The dancers created unique movements—spasms, convulsions, tics—that alternated with controlled and synchronized dance vocabulary. They alluded to scenes from Pina’s works or mirrored the current unsettled social and cultural context. At the close of the performance, the dancers put their clothes back on and returned to their seats among the audience.

Moving between past and present, or between the theatrical space and the audience, are not the only dualisms in Out of Context. In his review for The Guardian (June 20, 2010), Luke Jennings pointed out that the motif of dualism is present throughout the work: “Platel’s interest here seems to be in dichotomy. In chaos and order, animalism and classical harmony, outer dysfunction and inner transcendence. In any sincere appraisal of the human condition, he seems to be saying that both must be embraced.”

On March 2011, when visitors reached the sixth-floor studio at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, they saw a landscape of earth, leaves, sticks, and black feathers. Looking more attentively they also saw a man and a woman, both naked, lying side-by-side in darkness under the sound of dripping water somewhere behind them. They were the Japanese-American artists Eiko and Koma in their performance of Naked: A Living Installation. The white powder covering the surface of their bodies created a distancing effect between their flesh and the audience. In some way, it functioned like clothing that separated them from the rest of the world.

In their dances, Eiko and Koma usually present awesome cycles and processes from nature in which all beings are caught up. Although they don’t define their work as Butoh, their use of minimalism, metamorphosis, haunting visual imagery, and exquisitely controlled movements reveals the connection with its form and universal concepts. Butoh (“The Dance of Utter Darkness”) was born in the deserted lands of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and is rooted in both the mythic past and postwar Japan. Despite being inspired by Butoh and postmodern dance, Eiko and Koma have developed a primordial performative style in their iconoclastic work that is often referred to as “the elegy of art.”

Even though many Butoh performances display an obsession with the dark sides of the human body, especially its raw sexuality, the metaphysical images in Naked are completely desexualized. Instead, nakedness here encourages viewers to meditate on the mortality and ephemerality of the human body.

In late 2015, Xavier Le Roy presented both his work Temporary Title and his legendary solo Self Unfinished (1998) in Australia. He selected eighteen performers from Melbourne and Sydney to collaborate closely in the development of this new project. Le Roy has described this project as a moving landscape in which the human body is the primary medium of expression. In his approach, rather than instructing the performers to move using a specific technique, he proposed ideas that were discussed and actualized in movement. Also, in a series of open rehearsals, he invited the audience to participate in the process.

The performers blurred the boundaries between visual art, performance, and dance. They imitated a pride of lions, moving on their hands and knees, while patrons sat or stood around them. The project lasted six hours, and the audience could stay for as long as they wished. This experimental type of live performance allowed for the development of a collective and reflexive awareness between audience and performers. Le Roy explained in his lecture at Carriageworks that the performers were encouraged to move close to the viewers and talk with them (mostly about aging, time, change, and geography). John McDonald, art critic for the Sydney Morning Herald (November 19, 2015), commented upon this interaction: “The silence in which Temporary Title unfolds is an important aspect of the experience, as speech is one of the defining points of humanity. When the performers come over to talk with the audience it is as if they have reassumed human identity, freed from the spell that had transformed them into lions.”

Le Roy is renowned for his unique methods of exploring the limitations of the body, and the transformative role of the audience in shaping a performance. In the early 2000s, he began to create works designed to be experienced in an exhibition space and has been credited as one of the pioneering artists who brought dance into museums and galleries.

Another choreographer who applies nudity with the aspiration to change perceptions and taboos about the human body is John Jasperse. In 2012, his piece Fort Blossom Revisited, which is famous for a nude male duet that confronts the gaze of the audience in surprising ways, premiered at the Kitchen in New York. It features four performers, two women elegantly dressed, and two naked men. The dualism that develops between the different worlds of the men and the women is extraordinary.

Another piece that pushes sexual boundaries is Lloyd Newson’s potentially provocative production with DV8 Physical Theater, John, which we saw at the Onassis Cultural Center in Athens in 2014. The audience is faced with a circular stage on which, within the first four minutes, we witness a sadistic beating, rape, incest and death from a drug overdose. In the second part, John, who has just been released from prison, works in a gay sauna in London.

Final Thoughts

Throughout this article we have discussed the purpose of nudity in avant-garde dance performances from a phenomenological point of view that approaches the human body as a social and historical agent of political activity. The term “political” here is not used with the narrow meaning of communicating specific ideologies, but with regard to the broader role of dance in society, a role that should be understood in the sense that æsthetics may generate personal and collective change.

Not feeling bound by Kenneth Clark’s old distinction between “naked” and “nude,” we have been using the terms interchangeably while discussing how artists are using movement as a way to communicate ideas. In this sense, the body under the (voyeuristic) gaze of “the other” encourages reflection on whether nudity and vulnerability are merely a matter of shame and hiding or a universal condition that we cannot escape by resorting to the use of costume.

As part of the audience, we have seen many performances in which issues such as nudity, eroticism, and homosexuality were no longer forbidden. Given the complex relationship between art and consumerism, we wondered at times if nudity were necessary in many dance pieces or whether it merely followed a trend. The power of nudity to attract audiences is a reality that cannot go unmentioned.

Writing about the exposure of the dancing body in our neo-liberal society, in which humans have been turned into objects and all values have been stripped away, has seemed, at times, an issue out of context. Nevertheless, we hope that dancing bodies (and non-dancing bodies) will continue to express ideas about humanity and to signify their active resistance to the repressive forces of our society.

References

Carr-Gomm, Philip. A Brief History of Nakedness. Reaktion Books, 2012.

Conquet, Angela. “The Flesh Is Still Weak. So Is the Mind.” Dancehouse Diary 6.3, 2014.

Daly, Ann. Done into Dance: Isadora Duncan in America. Indiana University Press, 1995.

Jones, Amelia. “Survey” in The Artist’s Body, Tracey Warr, editor. Phaidon Press, 2000.

Hanna, Judith Lynne. “Dance and Sexuality: Many Moves.” The Journal of Sex Research 47.2, 2010.

Lepecki, André. “Skin, Body, and Presence in Contemporary European Choreography.” The Drama Review 43.4, 1999.

Maria Tsouvala is assistant professor at the Department of Early Childhood Education, of the University of Thessaly.

Katia Savrami, assistant professor at the Department of Theatre Studies of the University of Patras, is the author of a series of dance books and articles.

This piece has been excerpted and adapted from “The Human Body in Contemporary Dance: From costumes to nakedness,”published on-line in Critical Stages/Scènes Critiques, June 2016.