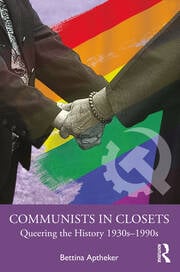

COMMUNISTS IN CLOSETS

COMMUNISTS IN CLOSETS

Queering the History 1930s-1990s

by Bettina Aptheker

Routledge. 255 pages, $44.95

HOMOSEXUALITY has long been a political football. Conservatives have accused queer people of all manner of immorality, criminality, and treachery. Those on the Left have been equally keen to associate same-sex behavior with upper-class decadence, antirevolutionary inclinations, and fascism. Marie Antoinette was defamed as a lascivious “tribade” in anti-monarchical porno-propaganda. Male “sodomy” was regularly criticized as the decadent privilege of aristocrats. Marx and Engels—like most men of their time—found “pederasts” distasteful, and unworthy of the same liberationist energies as the proletariat, Black people, and even women. However, the Russian Revolution of 1917, in overturning feudalism and the monarchy, also abolished the Tsarist criminal code’s antisodomy statute (under the broad principle that “the proletarian state does not intrude into the intimate lives of individual persons”). Some contemporary German socialists, including homosexual sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, lobbied for the repeal of the German anti-sodomy law (Paragraph 175).

In the 1930s, homophobia became a weapon in the culture wars for both Right and Left. In 1931, German socialists used homosexual outing as a smear tactic against the Nazis. Anti-sodomy legislation was reintroduced in the Soviet Union in 1933 along with other repressive Stalinist policies (such as the recriminalization of abortion). Male sodomy was made punishable by up to five years of imprisonment (Article 154a), and became grounds for sending dissidents and artists to the gulags. Author Maxim Gorky lauded the change, writing in Pravda (23 May 1934) to link homosexuality, the Western petit bourgeoisie, and German fascism:

In the land where the proletariat governs courageously and successfully [i.e., the USSR], homosexuality with its corrupting effect on the young is recognized as a social crime punishable under the law. By contrast, in a ‘cultivated land’ of great philosophers, scientists, musicians [i.e., Nazi Germany] it manifests freely and with impunity. There is already a sarcastic saying: “Destroy homosexuals—Fascism will disappear.”

Quite to the contrary, German fascists were about to exterminate homosexuals. The next month, in the “Night of the Long Knives,” Hitler began to consolidate power by executing opponents under the guise of purging homosexuals—not just from the military, but from society in general.

That was a highly abbreviated background on the European origins of the antipathy of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), toward homosexuals—something that is missing from Bettina Aptheker’s Communists in Closets: Queering the History 1930s–1990s. The CPUSA was founded in 1919 out of a left-wing split in the Socialist Party. These progressive parties had grown out of earlier labor movements and union organizing linked to international socialist movements of the 19th century. CPUSA helped found the Sharecroppers’ Union in the 1930s and continued defending Black civil rights throughout the 20th century. Membership surged in the 1930s with the Great Depression and alarm over fascism in Europe. Communists and socialists found common cause in the Popular Front, part of a global anti-fascist progressive alliance.

The Communist Party attracted a wide array of progressives: labor and union organizers, garment workers, farm workers, miners, steel workers, artists, and entertainers. Official membership peaked in the late 1940s, then declined after 1947 during the Cold War. The postwar “Red Scare,” a Communist witch hunt, was concurrent with a “Lavender Scare”—an attempt to purge “sex perverts” from the government. Earlier, at the outset of World War II, psychiatrists had convinced the Selective Service that homosexuals were mentally and morally unfit to serve in the military. This concern only increased with the Cold War. Due to anti-sodomy laws throughout the U.S., gays were also viewed as national security risks: their shameful secret made them vulnerable to Soviet blackmail and recruitment as Red spies.

Aptheker points out the tragic irony that CPUSA also purged homosexuals from the Party using the same “enemy within” rationale: they were a security risk—but for FBI recruitment and spying on the Left. Aptheker is, for many reasons, an ideal historian of closeted Communists. She was a “Red Diaper Baby”: both of her parents were lifelong Party members and part of a large contingent of Jewish leftists. Her father, Herbert Aptheker, was a leading Marxist historian and theoretician with seminal publications in African-American history. He became the literary executor of socialist intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois—one of the founders of the naacp. Bettina Aptheker became an official Party member in 1962 and “came out” as a communist at UC–Berkeley when she was a leader in the Free Speech Movement. She remained a Party member until 1981. Most importantly, she was a closeted lesbian until she met her future wife in 1979.

She has a celebrated record of activism and Marxist-feminist scholarship, which she detailed in her 2006 memoir Intimate Politics: How I Grew Up Red, Fought for Free Speech and Became a Feminist Rebel. That work generated much controversy in Marxist and African-American Studies circles for its revelation that her widely admired father had sexually molested her for almost a decade until she became a teenager. She sets that aside in the present book to credit him for inspiring her progressive values and introducing her to the leaders of leftist and Black politics. Nevertheless, she notes his streaks of sexism and homophobia. While he could never quite bring himself to deal with his daughter’s lesbianism, he discretely provided her with hints at the many closeted Communists he knew. It seems like the CPUSA (perhaps like all USA until the 1980s) operated under a policy of closeted discretion: as long as you didn’t explicitly come out, useful members could remain in the Party even while everyone knew you were “that way.”

Aptheker credits multiple other historians for having covered some of this territory in articles and monographs on leftist politics, union organizing, and queer African-Americans, as well as some detailed biographies of women activists. Four central chapters are dedicated to individuals. These are bookended by chapters providing brief but detailed and moving biographies of dozens of queer Communist Party members: one chapter on closeted (or highly discreet) comrades before the CPUSA lifted its gay ban in 1991 and a closing chapter on members still active after the ban was lifted, including Angela Davis. Aptheker and Davis have been friends since childhood. Davis is a philosophy professor and activist icon. Aptheker was active in the “Free Angela” campaign during Davis’ murder trial in the early 1970s. Aptheker later published The Morning Breaks (1975), an account of this global campaign and Davis’ eventual acquittal. Like Aptheker, Davis was once married to a man and came out as a lesbian later in life; however, she has not made sexuality central to her extensive political activism on race and incarceration. (Her continued political importance is evidenced by the controversy in Florida over inclusion of her work in the AP African-American Studies curriculum.)

Of the four main subjects, activist Harry Hay and playwright Lorraine Hansberry have been extensively researched by others. Hay (1912–2002) was a lifelong progressive activist on many fronts, but openly organizing for gay rights led to his expulsion from the CPUSA. Nevertheless, his activism and writings were inspired by his Communist roots. Hansberry (1930–1965) was “closeted” her whole life, tragically dying at age 34 of pancreatic cancer. She corresponded with the lesbian group Daughters of Bilitis and contributed (anonymously or under a pseudonym) to mid-century homosexual magazines. She was married to a man, then divorced, and had several women lovers later in life. As with most of the individuals in Aptheker’s work, it is unclear why precisely Hansberry remained discrete about her sexuality: the homophobia of the Communist Party, the Black community, her profession, or American society in general?

The other two main characters are perhaps less well known, yet they were leaders in both Communist activism and women’s rights: Eleanor Flexner and Elizabeth Millard. Both were white women who came from well-to-do families. Flexner (1908–1995) was a creative powerhouse. She initially followed in her mother’s footsteps as a playwright, then a drama critic. She joined the CPUSA in the late 1930s and went on to leadership in feminist and anti-racist organizations. She was in a “Boston marriage” with fellow progressive Helen Terry for most of her life. She became disenchanted with the Communist cause and left the CPUSA in 1956. Flexner then dedicated herself to researching and publishing an early work in women’s history: Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States (1959). She followed this with a 1972 biography of pioneering 18th-century English feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. She was stricken by the death of her partner in 1981 and then largely withdrew from the world.

Betsy Millard (1911–2010) joined the anti-fascist Popular Front in the 1930s as a Barnard undergraduate and became a member of the CPUSA in 1940. She continued a lifelong career in Communist-associated publications and internationalist women’s rights groups. Her 1948 pamphlet Women Against Myth is a powerful and prescient Marxist-feminist critique of society. At a time when many Communist leaders still saw women’s rights as a distraction from the battle for workers’ rights, Millard presented women’s rights as a labor issue. She also advocated for a broad platform of progressive causes, including the “rights of the triply-oppressed Negro women” (class, race, and gender). She closed her essay with an idealized view of Soviet society:

After a hundred years of the modern struggle for women’s equality, Soviet women are urged in their magazines to educate themselves and grow, to fulfill their production quotas and thus add to the happiness and well-being of the nation; while judging from the number of square feet given over to the subject in every issue of the Ladies Home Journal, the highest ideal of American womanhood is smooth, velvety, kissable hands.

However, a decade later, she quit the CPUSA, fed up with its hostility to feminism and gay rights (according to her niece). Aptheker also suggests that Millard and Flexner, like tens of thousands of other Party members, resigned in outrage after the publication of the “Khrushchev Report.” Nikita Krushchev’s secret address to the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, “On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences,” revealed Stalin’s campaign of repression, imprisonment, and “annihilation.” (He left out his own involvement in the purges.) Leaked to the press in 1956, the Report led to distress all around the socialist world. However, leaders of CPUSA continued to support the USSR as the bastion of proletarianism and defended Soviet military suppression of rebellions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968).

The leadership of the CPUSA (including Aptheker’s father) continued to support the USSR through the 1980s. Even after Stonewall, CPUSA also followed the lead of Soviets on viewing homosexuality as individualistic, petit-bourgeois degeneracy incompatible with a collectivist proletarian revolution. If anything, Apkteker argues, it became more homophobic. Even as the USSR was collapsing, Aptheker notes, the Party’s general secretary denounced Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring) at the 1991 National Convention in Cleveland. At the same meeting, it also debated and lifted its six-decade ban on homosexual membership. However, it was not until 2005 that CPUSA fully embraced the fight against LGBT oppression under the rationale that the “ultra-right” uses hatred against LGBT people as a wedge issue to divide the working class. Aptheker notes that this change in policy happened without the Party’s acknowledgment of its long history of homophobia and its use of it as a class wedge issue. Portraying homosexuality as intrinsically bourgeois meant ignoring socio-economically oppressed queer people.

Aptheker’s research is extensively drawn from diverse archives, including those of the CPUSA donated to NYU. She had to obtain special dispensation to access restricted files of members who were “disciplined” and purged from the Party. The book is theoretically savvy, yet with the accessibility and warmth of an oral history. Indeed, Aptheker frequently returns to her personal activist zeal and psychological angst as a closeted lesbian. Given her multigenerational experience in the Party, she enlivens her narrative with fond recollections of many of the activists she has known since childhood.

A central dilemma of the book is this: Why did Aptheker and others remain closeted members of a homophobic Communist Party? One reason she assumes as a given: until the late 20th century, the vast majority of same-sex-loving people were secretive about their sexuality, since they risked blackmail, dismissal, prosecution, and social opprobrium. (Sadly, many people remain closeted today for all these reasons.) However, maintaining Communist Party membership—despite the sexism and homophobia of its leaders—had special value. Aptheker’s deep affection for her closeted comrades demonstrates the abiding political and social companionship the cpusa provided. As journalist Vivian Gornick argued in The Romance of American Communism (1977), the Party gave many progressive Americans a shared intellectual community, a powerful rhetoric, and a global confederacy for serving the downtrodden and for improving society. It reminds me of the many gays and lesbians who became physicians, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts despite the professions’ homophobia and active pathologization of homosexuality until the 1970s. They all left their sexuality in the home closet in order to serve a higher mission.

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA. He is a child psychiatrist with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.