Writing a memoir is fundamentally a ritualizing experience, a literary rite-of passage that tends to occur when a writer is facing—and challenging thereby—the implacability of mortality. Gore Vidal wrote that Tennessee Williams “could not possess his own life until he had written about it.” Of his own life, Vidal snarled when asked if he would be remembered, “I don’t give a god-damn.” In a more contemplative mood, he once mused, “As for life? Well, that is a hard matter. But it was always a hard matter for those of us born with a sense of the transiency of these borrowed atoms that make up our corporeal being.”

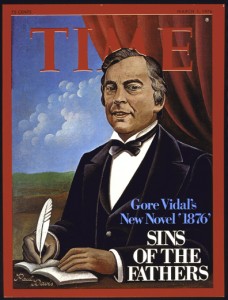

At 84, Vidal writes with an off-the-page vengeance as if from the brink of oblivion, while also giving frequent press, radio, and television interviews. He seems to be exorcising mortality with each memoir. Having once replied when asked about the memoir as a genre, “I am not my own subject,” he then acknowledged that “I have begun writing what I have said that I’d never write, a memoir.” This would become Palimpsest (1995), the first of three memoirs (to date). Vidal wrote in the dedication to the second, Point to Point Navigation (2006), that it was the “final memoir,” but with Snapshots in History’s Glare (2009) we have a third installment. Howard Auster, Vidal’s life partner for more than 54 years, who died in 2003, took copious snapshots of their life together. Snapshots is a visual memoir, a “memorial” tribute to Auster.

Mortality and its discontents are always stalking Vidal, who acknowledges that he moved back to the Hollywood Hills from Italy to be close to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. (“Things fall apart.”) The powerful undertow of mortality is present in Palimpsest—“I have just bought two plots for Howard and me in Rock Creek Cemetery”—while Snapshots concludes with three images of the cemetery and gravesite. The book visually traces the lifespan of an extraordinary relationship between two men. In public, Vidal always maintained an outward invulnerability, an unapologetic detachment, and would only acknowledge Auster as “my friend.”At Auster’s death, Vidal said he didn’t weep: “The Wasp glacier had closed over my head.” When he expressed profound loss, it seemed dispassionate: “You go into a room and it’s empty. One notices that. That’s about it.” When questioned about the secret to a long relationship, he always answered: “No sex.” During one interview, he scrunched up his nose and barked, “You can’t tell Americans that because they think everything is sex. … There’s nothing that can destroy a friendship as much as sex. What would you rather have? A friend.You can always get sex out there in the dark.”