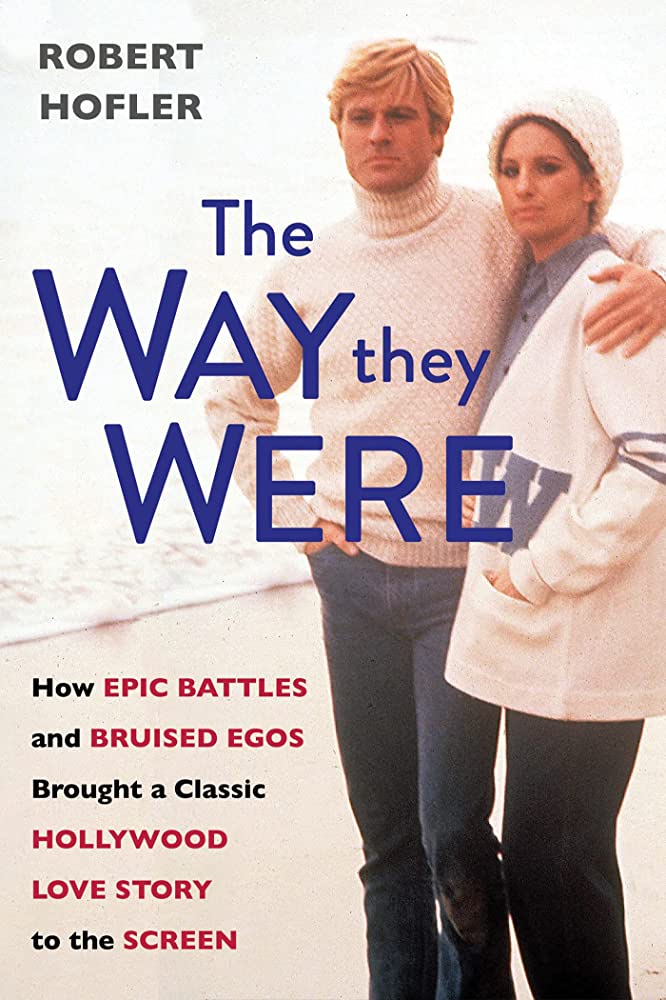

THE WAY THEY WERE

THE WAY THEY WERE

How Epic Battles and Bruised Egos Brought a

Classic Hollywood Love Story to the Screen

by Robert Hofler

Citadel Press. 278 pages, $28.

YIDDISH has entered the American language so extensively by now that most people have probably heard the word “shiksa”—especially if they’ve read Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. It’s the Yiddish word for a gentile woman. Robert Hofler’s new book on the making of the Barbra Streisand-Robert Redford movie The Way We Were (1973) is about its masculine equivalent, the much less euphonic “shegetz.”

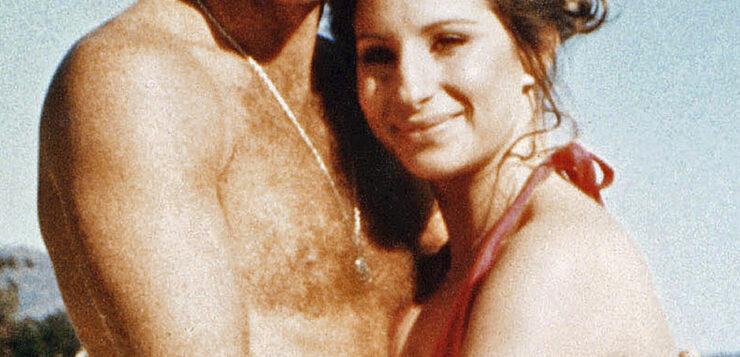

There are movies so memorable for themselves, or the way they were made, or what they reveal about the culture when they were made, that people are moved to write books about them. Whatever the emphasis, such books always end up being a cultural commentary on the time when the films were made, and Robert Hofler’s The Way They Were is no exception. Most of the book is about how the movie was made—the fights, egos, rewrites, scenes left on the cutting room floor—but what it also portrays is the way that Jews, and later gay people, came out to the American public. In Hofler’s view, The Way We Were was not only about a Jewish activist (Barbra Streisand) falling in love with a blond gentile jock (Robert Redford), but also the fictionalized story of the relationship between the movie’s screenwriter Arthur Laurents (both gay and Jewish) and a man named Tom Hatcher, the real-life shegetz in Laurents’ life and the inspiration for the couple in the film.

Laurents had already directed Streisand in a stage musical called I Can Get It for You Wholesale when producer Ray Stark asked him to write something for her after the success of Funny Girl. Laurents, whose résumé included Gypsy, West Side Story, Summertime, The Time of the Cuckoo, Home of the Brave, and numerous screenplays for directors like Alfred Hitchcock, not to mention affairs with two of his stars, Farley Granger and Anthony Perkins, went back to his own college days at Cornell as a liberal Jewish activist to create the role of Katie Morosky, the Jewish girl who falls for an apolitical jock. Streisand fit the role—she’d always defined herself as “a Jewish girl from Brooklyn.”

The 1960s may have been an era less sensitive to language than our own, but it’s still a shock to read that a critic at the New York Journal-American compared Streisand’s appearance to that of “an amiable ant-eater” or that Variety suggested “perhaps a little corrective schnoz job might be an element to be considered,” or that Richard Nixon (on the White House tapes) opined: “That Barbra Streisand is so obnoxious. Who can stand her? Her singing is so nasal, so whiny. And that nose—a real Jimmy Durante schnoz. But I guess she appeals to the New York crowd.” The New York crowd consisted of the gay men who flocked to a nightclub in the Village called the Bon Soir to hear her sing when she was still in I Can Get It for You Wholesale.

Like the nose in the story by Gogol, Streisand’s proboscis seems to have had a life of its own. It was both an example of fearless honesty—and a problem for the cameraman. “Whenever there was an outdoor scene,” The Way We Were’s cinematographer Henry Stradling Jr. said, “we had to build a canopy to shade her, because with direct sunlight on her nose, it looks terrible.” Laurents, ever the contrarian, said: “All this talk about her nose is nonsense. She actually has a lovely nose. It’s the eyes that are the problem.” Streisand was never averse to being seen as Jewish. In fact, she’d claimed it early on in her career. When Ray Stark was auditioning actors for Funny Girl, his film about Fanny Brice (the original Jewish girl from Brooklyn), his wife Fran, Fanny Brice’s daughter, was appalled by Streisand when she showed up at the audition in the sort of eccentric clothes found in thrift shops in the Village. Fran Stark wanted Mary Martin—a shiksa if there ever was one—to play the part. Stephen Sondheim told her the lead had to be Jewish. “And if she’s not Jewish, at least she has to have a nose.” Streisand had the nose. Indeed, it was her unconventional looks, Hofler theorizes, that assured the gay men who went to see her at the Bon Soir that you didn’t have to be attractive in the usual way to be desired. We speak these days of “authenticity,” but that’s what Streisand had from the beginning. And, given the times, this was quite refreshing. “Back in the 1950s,” Hofler writes, “Jewish performers, like Jack Benny, Dinah Shore, and George Burns, were still celebrating Christmas on their TV series. At the movies, a romance like Marjorie Morningstar featured Natalie Wood and Gene Kelly in Jewish roles. Even the film version of The Diary of Anne Frank cast the Irish American actress Millie Perkins as the lead, with her love interest being the perennial male ingénue Richard Beymer.” But by 1973, things had begun to change. In 1969, Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus came to the screen (a Jewish boy obsessed with a Jewish girl—played by Ali McGraw), the same year that Roth published Portnoy’s Complaint, the epic story of a Jewish boy’s obsession with shiksas, to be followed by numerous Woody Allen movies on the same subject, culminating in the Oscar-winning Annie Hall. And now, in 1973, we had the story of a Jewish girl falling for a shegetz. Both Ray Stark and Laurents would have been happy with Ryan O’Neal (who played opposite Streisand in What’s Up, Doc?). But Streisand and director Sydney Pollack (Tootsie) insisted that it be Robert Redford. Not only was Streisand “infatuated” with Redford, in Laurent’s estimation, but, he told Pollack: “You’re going to build up Redford’s part because you’re in love with him. I don’t mean homosexually, but he’s the blond goy you wish you were.” But this was the pot calling the kettle black, Hofler maintains. Laurents was so deep into intersectional self-loathing here that he “worshipped good looks, because, as he put it, ‘I never liked what I looked like.’” Redford, the designated shegetz, could not have been less interested in all this; married with four kids, he was suspicious not only of Streisand’s reputation for having affairs with her leading men, but also of the movie itself. “She’s not going to sing, is she?” he asked. “I (don’t) want her to sing in the middle of the movie.” The role of Hubbell seemed to him little more than that of a blond bimbo. But Streisand was smart enough to see that there would be sexual chemistry between them the moment they appeared on screen. And she was right—even if Redford, in an abundance of caution, was wearing two jockstraps during their scene in the sack. The real bone of contention, however, among Stark, Streisand, Redford, Pollack, and Laurents was the nature of the movie they were making. Ray Stark never quite got what Katie, the Streisand character, was supposed to be, and Redford wanted his role to be more active. Worse, there were two strains in the story—the political and the personal—and even when the movie came out, after many, many rewrites and last-minute cuts and additions, critics like Pauline Kael and Judith Crist felt the two never meshed. The romance was based on Laurents’ lifelong attraction to the shegetz. (“Arthur had a lot of Jewish friends,” said Laurents’ assistant, Ashley Feinstein. “He didn’t have Jewish boyfriends.”) The political part was based on his experience with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s search for Communists in the movie industry. The romance seems to be all it’s remembered for. When members of the first preview audience walked out before the film was over, Pollack knew he had to cut some of the political scenes. At the next preview, the audience remained in their seats sobbing. And sobbing is what the director, producer, and composer of the theme song (Marvin Hamlisch) wanted to hear. If The Way We Were was about the desire of a Jewish woman for the forbidden Other, another subject of The Way They Were is the way homosexual writers had to change the gender of their characters in order to succeed—which becomes clear toward the end of the book when we finally meet Tom Hatcher. It was Gore Vidal who one day told Laurents to go to Riley’s, a men’s clothing store in Los Angeles, and get a look at the new salesman. The salesman was Tom Hatcher: blond, good-looking, and very, very well built. (“How does Arthur get them?” asked William Inge.) Producer Howard Rosenman’s first impression when they met was: “I thought, typical shegetz.” He goes on to tell Hofler: “A ‘shegetz’ is taken from the Hebrew word ‘shikootz,’ which means ‘bug,’ which gives you an idea of what some Jews think of a ‘shegetz.’ … The Jew is the dynamic one, and when you fall in love with a vapid ‘shegetz,’ it’s because he’s the one you want to be, the beautiful one. That’s what attracts some Jews to Gentiles, the vapidity. There’s no drama.” Laurents is the Darth Vader of this book: “his memory was a vast storehouse of unsettled grievances, complaints and resentments.” Even Larry Kramer wouldn’t speak to him. (Kramer had his own experience with Streisand, who owned the movie rights to The Normal Heart.) The best chapter in The Way They Were is the epilogue (“The Reporter and His Subjects”), when Hofler describes his visit to Laurents, this man of all theatrical trades. At this point the minutiae of moviemaking give way to reflections that one can only get when the film is in the can. (The movie did quite well; the title song was number one for six months; Streisand to this day would like to make a sequel; Redford considered it a one-off.) Laurents confessed in an interview that at some point in his life the Jewish chip on his shoulder gave way to the gay chip. When Laurents was in London directing a revival of Gypsy, Hatcher, back in New York, got involved in gay liberation by going to meetings at the Firehouse. (At one point he writes Arthur to ask if activists always sleep with each other.) But Hatcher, despite being a blond beauty, was subject to a form of discrimination that Laurents never experienced—as the boyfriend of a much more successful man whose friends tended to dismiss him. “For years,” Laurents said, “people were cruel to Tom as the less notable half of a couple. At least they lusted after him, so there was that.” But that was all they saw in Hatcher. “Arthur did not want to face anything but that Tom was God’s gift to the world,” said his assistant Ashley Feinstein. “I wouldn’t say anything bad about Tom because Arthur had put him on a pedestal, although Arthur started realizing that all of Arthur’s fancy friends treated Tom shabbily”—so shabbily that Laurents christened the Broadway community that he had once loved “Chernobyl.” It’s hard to ascertain just what this relationship—so much a creature of its times—was like. In Hofler’s view, “The two men were deeply in love and committed to each other.” According to Laurents: “He was my reason for living. My reason for writing.” (“It was the bile that kept Arthur going,” said a London friend of Laurents.) Feinstein believed that “Arthur was afraid Tom was going to leave him, because he did leave him a couple of times. Arthur was always doing more to keep the relationship going.” To Howard Rosenman, it was simpler: “They were both terrible drunks,” though Hatcher went to AA and got sober before he died of lung cancer in 2006. In the summer they lived in separate houses in the Hamptons. Their neighbor in New York was sure the two men had poisoned his cat because it kept wandering into their garden. Of such details are marriages made, and Hofler, as his previous books about Dominick Dunne and The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson demonstrate, has a great eye for detail. As for the history of which Arthur Laurents and Tom Hatcher were a part—concurrent with all the dish in Hofler’s book, and there’s tons of it, is the cultural change their lives reflected, which is the real takeaway of this book. Laurents’ first play, Home of the Brave, was about anti-Semitism in the U.S. military. The Way We Were was a gay love story disguised by gender-changing. The two plays he wrote late in his life about Hatcher and himself as gay men, The Enclave and Two Lives, got little attention and are not much remembered. But the time between Home of the Brave and The Enclave was a time of great change. The film version of The Boys in the Band opened in 1970, three years before The Way We Were, but it took twelve more years before another major movie about homosexuality, Making Love, with Harry Hamlin and Michael Ontkean, came out in 1982, and it was a critical and financial bomb. In 1985, William Hurt won an Oscar for Kiss of the Spider Woman, Tom Hanks for Philadelphia in 1993, and Philip Seymour Hoffman for Capote in 2005. So, did The Way We Were have anything to do with the history of movies about gay people? You could make a list of television shows and movies that did, but it would not include The Way We Were. What Hofler’s book describes so entertainingly is a time when Jews changed their names, got nose jobs, and celebrated Christmas on TV, homosexual writers created heterosexual characters to survive, and a Jewish girl from Brooklyn became a surrogate for the longings of gay men: a picture of a shift in culture that came about in ways that now seem inevitable but weren’t back then. As Hofler notes, Black people are now thriving in the theater the way Jews of Arthur Laurents’ generation once did, to the point that Jews, the former outsiders, are now the Establishment. Such is the endlessly rocking washing machine of American assimilation.

Andrew Holleran’s latest novel is The Kingdom of Sand (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).