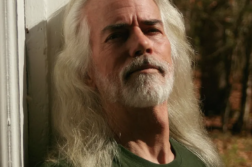

QUEER artist-provocateur extraordinaire Tim Miller delights with the publication of A Body in the O (Wisconsin), featuring new stories and performance texts. Four decades into his singular career, Miller continues to mine autobiographical material to create politically charged, multidisciplinary theatrical works. A progenitor of queer æsthetics, he remains as relevant and resourceful as ever. The memoir’s compelling essays amplify and provide insightful backstories for his social-justice-infused performance scripts.

John Killacky: In the opening essay of your new book, you write that “Solo performers are first responders.” What do you mean by this?

Tim Miller: I have seen again and again how performers are often the first to begin naming and tackling systems of injustice. As an artist of 21 confronting the AIDS crisis, I saw that not only were we not getting any help from the government, we were getting actual malevolence from the Reagan and Bush administrations as they did nothing to tame the pandemic. The earliest performers responding to AIDS in 1980 and ’81 were playing the role of first responders. With other issues we face, theater and performance are often one of the first tiers of response, especially solo performers, slam poets, spoken word. There are all kinds of ways that this manifests now.

I teach so much, working with literally thousands of young artists every year all over the country. Long before there were hashtags, I had witnessed hundreds and hundreds of what I now think of as #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo pieces years before they coalesced into movements. Through these moments of storytelling and witness, we become first responders.

JK: In 1978 you moved to New York, and two years later you co-founded what became the most important alternative venue supporting avant-garde artists, P.S. 122. Talk about the performance scene at that time.

TM: It was quite interesting at the end of the ’70s. I was still a teenager and things were in flux. The city had fallen apart and was in deep fiscal crisis; there was such chaos. Culturally I felt I was arriving into a vacuum. I felt something new was to come to life. In less than two years, I was signing paperwork with the two other co-directors of P.S. 122 to establish a nonprofit. Our first fall, I organized what I’m told was the first ever festival of queer men’s performance art.

JK: After nine years in New York, you returned home to California and, in 1989, cofounded another organization, Highways Performance Space in Santa Monica. Why did you decide to return, and how different were West Coast æsthetics?

TM: When I arrived in NYC in 1978 flush with the fiercer queer politics of California, I was frustrated by how much less political the New York art world and gay communities were compared with my home state. I had a good adventure in New York, touring all over the world at 23 and being the youngest person commissioned by the BAM Next Wave Festival, but I realized that the most interesting political work and the performers I felt most aligned with were all in L.A., including Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Los Angeles Poverty Department, Rachel Rosenthal, and Ron Athey. By 1987 it was time to go home.

JK: In 1990, the National Endowment for the Arts denied fellowships to you, Karen Finley, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes because of the queer content in your work. The “NEA Four,” as you became known, sued the federal government and spent the next eight years taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court. Talk about living through this experience.

TM: It is such a big part of my biography, but it was part and parcel of a general assault I experienced from our government. Even during this Culture War period, I always felt more attacked by my government around hiv/aids than I did by the NEA stuff. Going to funerals every few days was more distressing to me. That said, spending eight years of your life in endless lawyer meetings, conference calls, and depositions was a big challenge. It also happened to be one of my most creative times, not just in my life, but in our country. The flowering of queer culture in the ’90s was incredibly energizing and rich. I never had audiences come so intensely to the work. Pre-Internet, the urgency with which people came to the theater was very particular.

JK: As a performer, writer, curator, and

activist, you remain as prolific as ever, creating shows and touring the world, publishing, and teaching. Has the itinerant nature of your life for forty years taken a toll?

TM: It certainly has. My best year was 2017 in terms of number of performances, earnings, and awards. It also kicked my butt and made me realize I was pushing things health-wise. I was needing to take care of some heart issues, which is something I was making work about at that time and is part of A Body in the O. Since I turned sixty in September, I’m trying not to feel like I have to do every single gig. Traveling during winter is just too hard for this L.A. boy. I also don’t want to be away from my husband Alistair so often. We’ve done it for 25 years, but it’s more fun spending time together. I am a freelance performer, I love writing shows and essays, but the only way I make money is through residencies and performances. It is also at the heart of my creative mission. I just need to find a better balance. Thirty-five weeks on the road was about sixteen too many!

JK: Throughout your remarkable career, your artistic praxis advocated for LGBT civil rights by exploring gay identity, AIDS, and marriage and immigration equality. The last chapter of your new book includes an excerpt from your 2016 performance, Rooted, and provides a full-circle perspective of your explorations. Talk about this piece.

TM: Rooted closes out the story of our immigration and marriage equality struggles that my Australian husband Alistair and I went through to keep him in the U.S. These political issues were at the heart of my work for the last twenty years. I had saved a copy of my great-great-grandparents’ marriage license from 1865. Once Alistair and I were married on the very day DOMA was overturned, I wanted to find connectivity to my great-great-grandfather (a Civil War veteran from the N.Y. 44th regiment), to dig deep, follow the ancestors, and keep doing the social justice work in these terrible Trump times. It is a piece acknowledging my ancestors and my own mortality.

John R. Killacky is a legislator in the Vermont House of Representatives.