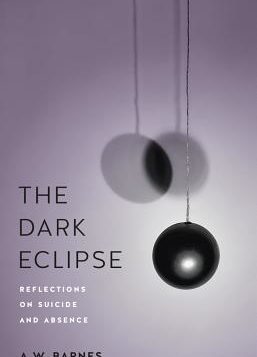

The Dark Eclipse: Reflections on Suicide and Absence

The Dark Eclipse: Reflections on Suicide and Absence

by A.W. Barnes

Bucknell University Press

126 pages, $24.95

IN OCTOBER 1993, the body of Mike Barnes, a lawyer for Morgan Stanley, was found in a hotel room in Manhattan. Mike had ended his own life. His brother Andrew or “A.W.,” who has written this powerful memoir, was 29 years old at the time. In the years since then, A.W. has wrestled not only with his brother’s suicide but also with his relationship, or lack of one, with his family (other than his mother), and especially with his father. “I blamed my father for Mike’s death. I still do,” he writes. What’s more, he has not been able to forgive his father.

In the years that have passed since Mike’s death, A.W. has also been hard-pressed to remove the ghost of his brother from his life. Nor does he really want to. Through various documents related to Mike’s death—police records, autopsy reports, and the like—the author

David Gillespie, officially retired, teaches religion and philosophy at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina.