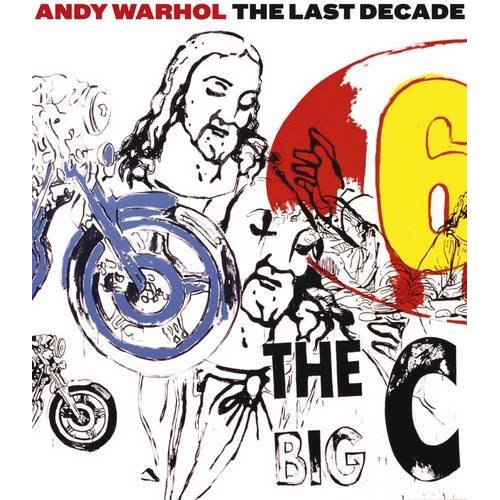

Andy Warhol: The Last Decade

Andy Warhol: The Last Decade

thom th Joseph D. Ketner II

Prestel Publishing. 223 pages, $60.

ANDY WARHOL is best known for the Pop phase of his work, for fusing high art with low, starting in the 1950’s. “By the end of the 1970’s he felt trapped by the public’s expectations of him to present images of popular culture and to embody fame and social celebrity through mass media,” writes Joseph D. Ketner II, in Andy Warhol: The Last Decade, a collaborative venture between the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. “He had grown weary of the continuous parade of society portrait commissions and physically exhausted by the nightly clubbing on the New York social circuit.”

In fact, Warhol’s future might have been different had he not met Jean-Michel Basquiat in the fall of 1982. Basquiat breathed new life into Warhol’s love of painting, and exerted enough influence that Warhol largely stopped making movies after Bad in 1976. Keith Haring, one of the seven contributing essayists in the book, recalls that “Andy trusted Jean even to the point that he would actually let him cut and sculpt his hair.” Basquiat and Warhol, Haring writes, “exercised together, ate together, and laughed together,” even if the rest of staff cast a not-so-delighted eye on the duo. “Basquiat disrupted their schedules and filled the Factory with sweet-smelling pot smoke,” Haring writes, “but Andy seemed happy to defend Jean and to challenge their conservatism.”

Keith Hartley’s essay, “Andy Warhol: Abstraction,” takes us into the artist’s relationship with New York’s Abstract Expressionists. Warhol, who admired Jackson Pollock, saw the Abstract Expressionists as “aggressively macho.” Pollock’s crowd was, according to War-hol, “hard-driving, two-fisted types who’d grab each other and say things like ‘I’ll knock your fucking teeth out’ and ‘I’ll steal your girl.’ The toughness was part of a tradition, it went with their agonized, anguished art. They were always exploding and having fistfights about their work and their love lives.” (According to artist Larry Rivers, Pollock’s homophobic behavior included asking every homosexual he met, “Sucked any cocks lately?”)

Warhol, never one to retreat from a confrontation, couldn’t resist annoying the Abstractionist thugs. Perhaps that’s why his friends called him Drella, a name that was a combination of Cinderella and Dracula. “I certainly wasn’t a butch kind of guy by nature, but I must admit, I went out of my way to play up the other extreme,” Warhol wrote of his time with these guys. Rejected by the Abstract Expressionists for being gay and for his love of commercial art, Warhol cultivated what Hartley calls a “contrary stance.”

In the 1950’s and 60’s, Warhol repeatedly stated that art had to reflect the daily culture. As Keith Hartley remarks in his essay “Abstraction,” the “snobbish distinctions between fine and commercial (so-called high and low) art were no longer valid.” Hartley goes on to quote from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: “A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.” Later, under the influence of Jackson Pollock and painters like Ellsworth Kelly, Warhol came to paint works like 1963’s Red Disaster, which demonstrated his fondness for the so-called clean machine æsthetic.

His “piss paintings,” influenced by Neo-Dadaist artists and Pablo Picasso, caused him to paint with a sponge mop. In his diary, Warhol relates how he asked his handsome assistant, Ronnie Cutrone, to “try to hold it until he gets to the office, because he takes a lot of vitamin B so the canvas turns a really pretty color when it’s his piss.” “For all their scatological daring (and humor),” writes contributor Gregory Volk, “these paintings are also surprisingly nuanced and evocative. Some suggest the delicacy and solemnity of exquisite thousand-year-old Chinese ink landscapes….” (Strangely enough, the far more scandalous “cum paintings,” while acknowledged, are not reproduced in the book.)

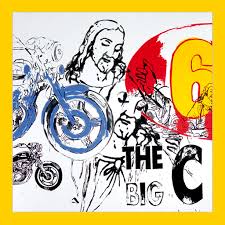

Just a year before his death, Warhol painted a series of self-portraits. Here we have, in Volk’s words, “a reddish-orange Warhol with fierce, piercing eyes, a slightly open mouth, and gaunt cheeks,” an unnerving work that Volk compares to a zombie, as if Warhol “already seems to have one foot in the grave.” Warhol also began a series of religious paintings, such as The Last Supper, and a slew of acrylic and silkscreen works like Heaven and Hell are Just One Breath Away, The Mark of the Beast, and Repent and Sin No More. Volk observes that throughout all of Warhol’s various styles, but especially in the portraiture, there exists the influence of his childhood experiences of going to the Byzantine church with its egg tempera and gold leaf icons.

The book’s contributing writers often repeat biographical information. There are a couple of editing glitches, such as when one contributor calls Warhol, who was a Byzantine Catholic, an Eastern Orthodox Christian. But these are relatively minor sunspots in an otherwise noteworthy addition to the Warhol canon.

Thom Nickels’ books include Philadelphia Architecture, Tropic of Libra and Out in History. His novel Spore

will be published in June.