I FIRST DISCOVERED James Kirkwood’s 1972 novel P. S. Your Cat Is Dead in 1974 at the now defunct Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop on Christopher Street. While waiting for my train back to Poughkeepsie, I became so engrossed by the novel’s fast-paced antics that I let one train depart, and then another, and yet another, until I finally had to take the last train of the day or resign myself to sleeping overnight on one of the carved oak benches that filled the waiting room in Grand Central Station.

The novel was simply too engaging to put down. Jimmy Zoole, having arrived at the theater earlier that day to learn that he’d been replaced by another actor, returns to his five-story walk-up in a soon-to-be-demolished building in Hell’s Kitchen on New Year’s Eve only to discover his girlfriend Kate hurriedly packing. She had hoped to finish moving out before Jimmy returned home from rehearsal. The bitter exchange that precipitates her eventual departure inadvertently leads to his discovery of a cat burglar under his bed—the very one who had already robbed the apartment twice in recent months, and who had now returned for a third try on New Year’s Eve. Jimmy accidentally knocks out the intruder and, uncertain what to do with him, ties him up over a heavy butcher block next to the kitchen sink, pours himself a drink, and sits down to weigh his options.

First published fifty years ago, the novel proved an offbeat hymn to gay liberation. Jimmy’s attempts at heteronormativity have led him to a dead end. (When a fellow actor is asked if he thinks Jimmy’s front teeth have been capped, he replies: “Zoole’s whole life is capped!”) Uptight Jimmy is unsettled not simply by Vito’s repeated attempts to coax him into bed, but by the sexually irrepressible cat burglar’s casual acceptance of homo- and bisexuality. “Queer is a word like tall. Everybody’s a little tall, even midgets, it’s how tall,” Vito explains. The novel tells readers who play by society’s rules to stop worrying about what other people think and take a chance on a different kind of love. The new year dawns with Jimmy mulling over Vito’s invitation to move with him to Mexico, where they can live cheaply together for an entire year on the proceeds of Vito’s latest heist while Jimmy works on the novel he wants to write.

In early 1970s popular culture, gay people did not “meet cute,” so P. S. Your Cat Is Dead offered a radical departure from the norm. The novel held out the fantasy of a “humpy” 25-year-old cat burglar dropping through a broken skylight directly into one’s bed. While there’s nothing sexually explicit in the novel, readers experienced a frisson at the thought of having a bare-assed stranger tied up in one’s kitchen, daring one to take advantage of his proffered butt. (‘Take a bite of my ass, it’s a real peach.”) But surely the greatest delight for readers was provided by the badinage between Vito and Jimmy, which proved as witty and fast-paced as the exchanges delivered in 1930s screwball comedies. Gay readers now had our own screwball comedy in which a high level of sexual energy results from the verbal thrusting and parrying of two seemingly mismatched partners.

In a season when James Leo Herlihy’s Midnight Cowboy (novel, 1965; film, 1969) offered the poignancy of two mismatched friend-lovers whose escape from seedy, wintry Manhattan to sunny Florida proves heart-breakingly futile, readers welcomed the hope that straightlaced Jimmy and anything-goes Vito might succeed in Mexico in ways that Joe Buck and Rico Rizzo could not. (Kirkwood and Herlihy were onetime lovers who remained close friends and confidants until Kirkwood’s death.) At a time when gay men were struggling to redefine love, P. S. Your Cat Is Dead offered the hope that non-normative relationships might not only succeed but could be enjoyed with gusto.

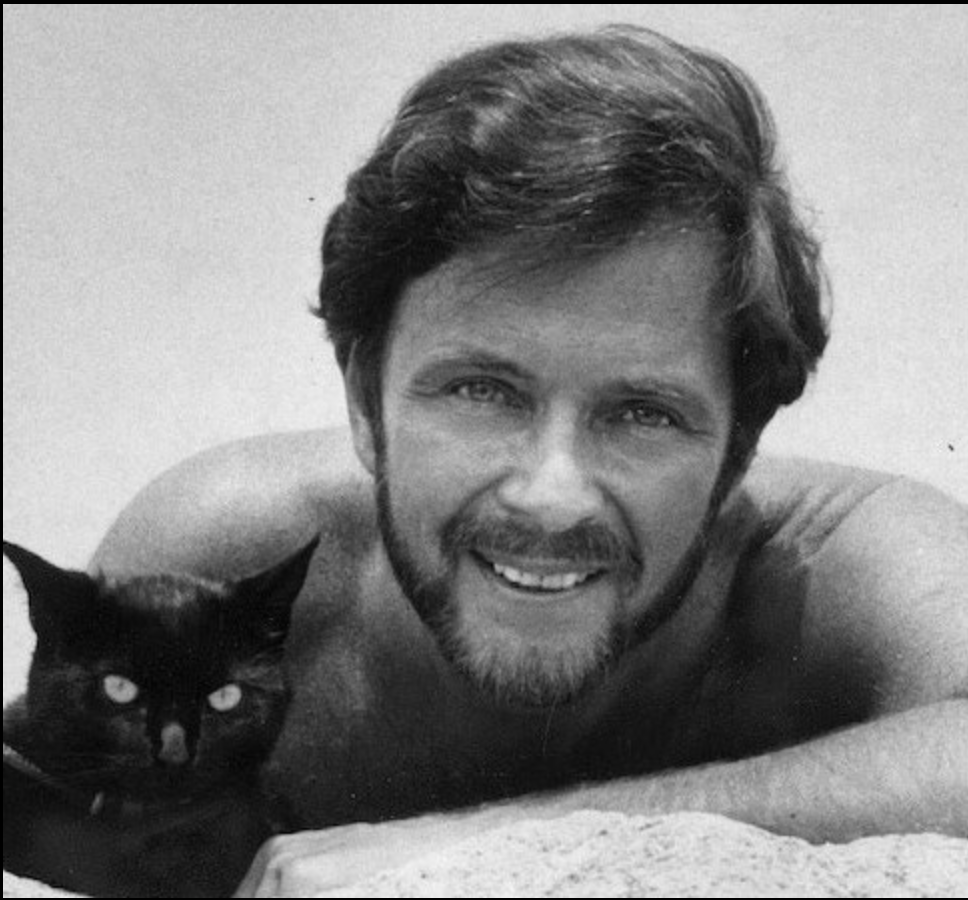

The success of Kirkwood’s novel was repeated in 1975 by his play of the same title, which quickly became a staple of regional theaters. Indeed, mounting a production of P. S Your Cat Is Dead! (the play’s title gained an exclamation point) offered a litmus test for a theater’s willingness to be provocative. While the novel only asked readers to imagine Vito’s nudity, the play required that the actor be naked on stage from the waist down. A theater had two possibilities regarding how it staged the play: either position the kitchen counter perpendicular to the stage apron, so that the audience looks at Vito’s naked butt and legs in profile for the better part of the performance; or position the counter to hide the naughty bits from the audience and allow the shocked looks on the faces of Jimmy’s visitors to make the point as they enter the apartment. Undertaking the role of Vito required an extraordinary brio on the part of an actor. A young Tony Musante was cast in the original production, while film veteran Sal Mineo was rehearsing to play Vito in the San Francisco premiere when he died in a random act of street violence shortly before opening night.

Alas, like the reputation of its author, P. S. Your Cat Is Dead has not aged well. The breezy attitude toward casual sex in both the novel and the play version wore thin with the emergence of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. An attempt was made to recapture the magic in a 2002 film, but it only demonstrated just how much a product of the ’70s Kirkwood’s work was. The producers tried to update the action by moving it from crime-infested ’70s New York to narcissistic Los Angeles at the start of the new millennium. Kirkwood, for his part—after being celebrated for writing the book for A Chorus Line (1975) with both a Tony Award and a Pulitzer Prize—saw his career steadily lose momentum until he died (presumably of AIDS-related causes) in 1989. But this does not erase the importance of Kirkwood’s novel and play as a blow against social claustrophobia in favor of sexual liberation.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the Univ. of Central Arkansas.