Keith Haring: The Political Line

The de Young Museum at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Nov. 8, 2014 to Feb. 16, 2015

Keith Haring: The Political Line

Keith Haring: The Political Line

by Dieter Buchhart, et al.

Prestel. 272 pages, $65.

IN 1980, graffiti-inspired chalk drawings proliferated throughout New York’s subway system. Keith Haring’s whimsical, cartoonish iconography was everywhere. Zapping spaceships, pulsing TVs, barking dogs, crawling babies, flying angels, leaping porpoises, and smiling faces abounded.

Haring’s “tagging” was soon legitimized by the art world; his first gallery show was in 1982. One year later he was featured in biennial shows at the Whitney Museum and at the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavillion in São Paulo. Before long he was collaborating with Andy Warhol, Madonna, Grace Jones, Jenny Holzer, and Bill T. Jones in galleries, museums, theaters, outdoor spaces, and dance clubs. Next, his artistic œuvre expanded to include ink drawings, woodcut prints, paintings on tarpaulins and wood, aluminum sculptures, sets and costumes, and large-scale outdoor murals in New York, Tokyo, San Francisco, Paris, and Melbourne, and on the Berlin Wall. By 1986, his very own Pop Shop in Soho sold branded merchandise, including pins, T-shirts, calendars, watches, magnets, and prints.

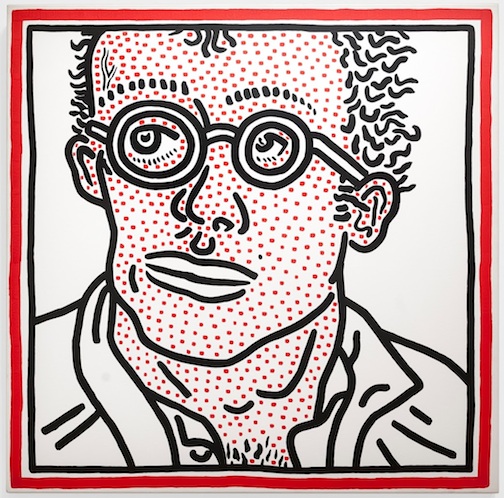

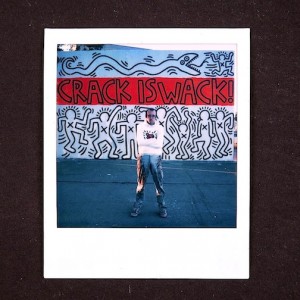

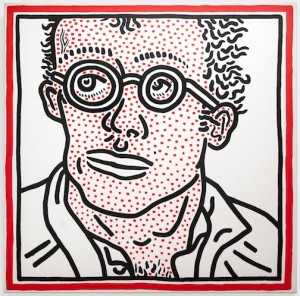

In 1988, Haring was diagnosed with HIV, which only seemed to escalate his artistic output. He was ubiquitous, even designing a label for Absolut Vodka and a carousel for an amusement park in Hamburg. Two years later, at the age of 31, he would be dead of AIDS. What he achieved in just ten years of public art making is astounding. Since his death, there have been many major museum retrospectives worldwide. The most recent was at the de Young Museum in San Francisco late last year and early this year. What was distinctive about this exhibition, Keith Haring: The Political Line, was how his effervescent, candy-colored pop æsthetic is viewed through the artist’s political activism. Even before his furtive subway chalk drawings, Haring was posting absurdist agitprop collages, guerilla-style, on walls and lampposts, composed of headlines from The New York Post to create messages like “Reagan’s Death Cops Hunt Pope.” A few of these early ironic collages are featured, along with some of the subway pieces. As his fame grew, Haring remained dedicated to grass-roots activism, and this commitment was aptly on view at the de Young. For an anti-nuke rally in 1982, he produced 20,000 copies of a poster showing a radiant child atop a nuclear mushroom surrounded by angels, which he handed out for free. Also fierce in his opposition to racism, he created a 1985 poster called Free South Africa that highlights a black-silhouetted man with a white noose around his neck trampling a smaller white figure. His outdoor mural Crack is Wack (1986) remains powerfully on display in Manhattan and is now a designated city landmark. Child welfare was another major concern; some of the large-scale murals he created with children were featured, including the one he made with 1,000 New York City kids celebrating the Statue of Liberty (1986). Many are still installed in the hospitals, churches, and day care centers that originally commissioned them. Haring was always out as a gay man and donated numerous designs for LGBT causes, notably ACT UP, National Coming Out Day, and A Day Without Art (World AIDS Day). These images were set in elegiac relief, mementoes of a life lost too soon. Most iconic perhaps is his 1988 Silence=Death acrylic on canvas showing a pink triangle filled with his schematically outlined figures covering their eyes, ears, and mouths. Notebooks of the numerous drawings of penises that he did in front of Tiffany’s and the Museum of Modern Art are fun to see as well. His 1985 painting titled Untitled (Self-Portrait), in which his own face is covered with red spots, was grimly prophetic. A raw sexual energy permeates his later works, as depictions of disease and death come to dominate. In many of these drawings, amorphous, multi-limbed, grotesque monsters are being penetrated through various orifices in a frenzied kinetic energy. This work hints at new directions for the artist that were never fully realized due to his premature death. The coffee-table catalogue from this exhibition is gorgeous, beautifully reproducing more than 200 works. Insightful curatorial essays and interviews contextualize this prodigious artist’s life with a focus on his social activism. While he saw himself as a provocateur, his work was never didactic. He himself best captures this approach: “I don’t think art is propaganda; it should be something that liberates the soul, provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further.” If Haring were still alive, he would only be 56 years old. Just imagine what his art would be telling us now.

John R. Killacky is the executive director of the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts in Burlington VT.