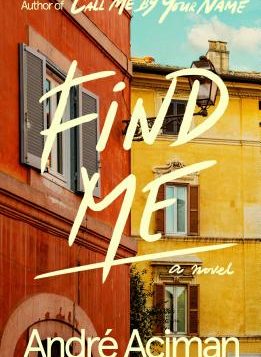

Find Me

Find Me

by André Aciman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

272 pages, $27.

IN ANCIENT GREEK, the verb opsizo means to arrive too late at the feast. “Or to feast today with the weight of all the wasted yesteryears,” as one character explains in André Aciman’s beautiful new romance, Find Me, a sequel to his enormously popular novel Call Me By Your Name (2007).

Many “wasted yesteryears” have passed since the events of the earlier novel. The teenage Elio is now a successful concert pianist, alone and unable to talk about the “someone” who was once in his life. Oliver, the graduate student he fell in love with one enchanted summer, has established himself as a professor in New York. Marriage, which he thought would “turn over a new leaf,” has done no such thing. He has “never recovered” from the pain of scuttling Elio. Elio’s father, now divorced, keeps “true life at bay” by “going about one’s daily life with all its paltry joys and sorrows.”

In three novella-length sections, Aciman presents these achingly poignant stories, each a variation on the trope of belated arrival. The first story belongs to the father. On a train to Rome to deliver a paper on the “unimaginable loss” of thousands of texts from the ancient world, he shares his compartment with a glum-looking woman half his age, with whom he strikes up a conversation. Her name is Miranda. (We’re meant, I think, to recall that most famous of literary Mirandas, the heroine in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a girl torn between dutiful love of her father and starry-eyed infatuation with a prince who washes up onto her island home.)

Miranda is beautiful, direct, inquisitive, and world-weary. She can read people well, and this encourages the father—Miranda nicknames him Sami—to open up, despite the fact that he detects in her an “embittered, impassive, injured” heart. He tells her about a brief affair he once had with a woman he’d met almost three decades earlier, someone he has never been able to forget. “I am always trying to retrace my steps back to a spot where I should have jumped on the ferryboat headed to the other bank called life but ended up dawdling on the wrong side of the wharf,” he tells her. When Miranda guesses that his marriage was “the wrong ferryboat,” he opens up even more, telling her about the end of his marriage, about his son, about the “too many memories” that Rome holds for him. When they arrive in Rome, Miranda invites him to join her for lunch at her father’s place.

Over white wine and fish, their conversation becomes ever more playful. “I needed to caress her, to put my arms around her,” Sami says. Soon Miranda is revealing more about herself as well: her relationship to her father, who is dying, and her relationships with the previous men in her life. “I have very little that anyone might want at this point,” she tells Sami, “and, as for what I want, I wouldn’t even know how to spell it out.” Looking at him, she adds, “But all this you know already.”

Aciman is a master, as was Henry James, of the way that brainy people flirt. He beautifully traces how these two fragile people—one the bookish professor who wants to “reconnect with the person I used to be and lost track of,” the other a woman who has “never found someone who mattered enough”—dance a cautious but seductive do-si-do around each other. As the attraction deepens, Miranda peremptorily invites Sami to “do crazy … do in this lifetime everything you couldn’t do in your humdrum, day-to-day, sterile, other life.”

It is to Aciman’s credit that he takes a potentially hackneyed plot—the young person who makes an older person “want things I’d thought were forever gone from my life”—and refashions it into a tender, passionate, and believable love story. In this version, both the prince and the princess are brought back to life. Falling in love again offers the possibility of a “beautiful commutation” from the stale sentence of “living as if life were an extended waiting room.”

In the second part, the narrator is Elio. One evening, at a chamber music concert in Paris, he meets a man twice his age, who, in his gaze, promises “something totally kind and guileless.” After the concert, they go off to a bistro together. As their conversation moves forward—two brainy people, again—Elio can sense where the man, Michel, is headed. “Just kiss me, will you,” he thinks, “if only to help me get over being so visibly flustered [italics in the original].” Two days later, they meet again, and the candor increases. Elio tells him that since his teenage love affair, all of his relationships have been short-lived: “I never really let myself go or lose myself with others.” Like father, like son.

When Michel invites Elio to his childhood country home—“late-eighteenth-century Palladian”—Elio jokes that he feels “like Cinderella.” Indeed, there are many fairy tale elements to this novel, which, depending on the reader’s taste, will either irritate or enchant.

For all the Cinderella-like elements, dark notes invade the story, too. Michel understands how vulnerable he is as the older pursuer: “you could hurt me, devastate me actually,” he tells Elio. And then he shows him a mysterious musical score, once owned by his own father, who had also been a concert pianist, with a dedication inscription that suggests both a romantic and tragic backstory. (There’s a sly reference to The Tempest here, too.) “I never got to know who was the man behind the man I thought my father was,” he says. As this part of the novel winds up, Elio tells Michel: “I don’t want this to end.”

In the third part, the narrator is Oliver, 44 years old and married to a woman named Micol. It’s a relationship Oliver describes as “a perfect team.” Privately, however, his life, too, is at a dead end. Elio remains the “one person who was never absent for me.” Oliver imagines that Elio would “love nothing more than to hear from me.” “Find me,” he imagines Elio whispering.

What happens to all these people, and all this longing, is revealed in the novel’s coda, which, again, some readers may find to be more fairy-tale-esque than a modern novel can accommodate. And yet, who doesn’t want to believe that our wasted years, “unbeknownst to us, end up making us better people”? Who doesn’t want to believe that partings are never really final?

Gorgeously lyrical, unabashedly fanciful, Find Me is one of those delicious literary confections that turns out to be more than just a mess of empty calories. Witty, wise, breathtakingly elegant, Aciman’s novel ultimately tweaks the nose of Henry James and his arch, ironic tragedies, opting instead to embrace and celebrate the brave new world of Shakespearean romance. Believe Me is what this novel invites us to do: to believe that the feast, no matter how late we arrive at it, no matter by what long, aching path we manage to get there, may still be available if we can just bring ourselves to “do crazy.”

Philip Gambone is the author of a short story collection and of the novel Beijing.