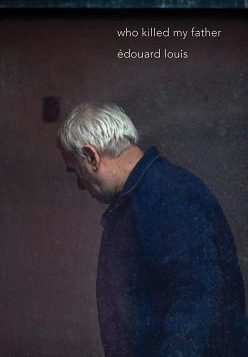

Who Killed My Father

Who Killed My Father

by Édouard Louis

Translated by Lorin Stein

New Directions. 96 pages, $15.95

“FROM MY CHILDHOOD I have no happy memories.” With that arresting sentence, Édouard Louis (born Eddy Belleguele) opened his stunning debut novel, The End of Eddy (2014), a work of autofiction that quickly propelled the 22-year old author onto the international stage of LGBT writers. In unflinching detail, Louis described growing up in a poor French village. It was, and remains, a world where “people never go anywhere,” a world where to be different in any way meant you were persecuted.

In his subsequent History of Violence (2016), Louis continued his gay odyssey, now focused on his post-village decampment to Paris, where, as a young, college-educated intellectual, he picked up a bit of rough trade who raped and nearly killed him. Even more than the first book, History of Violence incorporated the voices and points of view of the others in the “plot,” among them the bureaucratic police, his uncomprehending sister, and even the rapist, Reda, for whom he expresses a fleeting sympathy. The book explored how one’s own story can become muddied, even lost, in “official” accounts, unsympathetic misunderstandings, and incomplete recollections until “it disappears for good and can never be retrieved.”

This theme—the existence of competing versions of the truth—is taken up again in Louis’ third literary inquiry into the material of his young life. Who Killed My Father is a small book, but it packs a big punch. Early on, Louis declares that what he is writing “does not answer to the standards of literature, but to those of necessity and desperation, to standards of fire.”

Philip Gambone’s interview with Édouard Louis appeared in the March–April 2018 issue of this magazine.