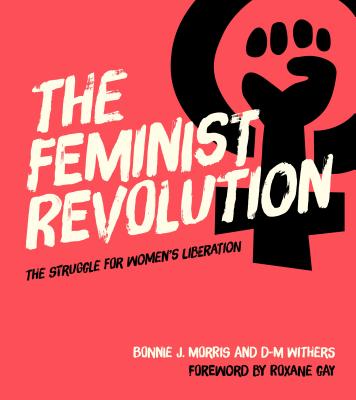

The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation

The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation

by Bonnie J. Morris and D-M Withers

Smithsonian Books

224 pages, $34.95

THIS BOOK packs a punch—or rather, multiple punches—reflecting the power and energy of women’s struggles for political and social equality in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. Like a quilt stitched by a sewing circle, The Feminist Revolution depicts a dizzying array of actions that show the scope and variety of women’s efforts in those years. The work is told from an Anglo-American, Western perspective and is illustrated with striking black-and-white archival photos amplified by grassroots activists’ words.

The authors’ narrative essays in ten thematic areas recount events set mainly in the U.S. and Britain. Bonnie J. Morris is professor of women’s studies at Georgetown and also teaches at George Washington University. She has written The Disappearing L: Erasure of Lesbian Spaces and Culture(reviewed in the March-April 2017 issue) as well as novels and plays, and has received three Lambda Literary awards. D-M Withers, a research fellow in media and film at the University of Sussex, England, is a respected theorist concerned with cultural memory and the politics of its transmission. She has curated numerous exhibitions on the women’s movement.

The Feminist Revolution is an oversized book with a standout red, white, and black cover. Morris and Withers describe it as not a history but rather a “representation” of one era of women’s struggle intended to celebrate the “political, strategic, and cultural diversity” of the whole movement. Refreshingly, photos from familiar events, such as Hillary Clinton’s speech before the U.N.’s 1995 Fourth World Congress on Women in Beijing, are outnumbered by pictures of more obscure yet equally riveting events, such as the Wages for Housework campaign that arose out of a women’s collective in Italy in 1972. Even buttons can convey a powerful message: “Ordain women or stop baptizing them”; “Viva la Vulva!”; and “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met?”

What is feminism? British philosopher Lorna Finlayson defines it as a movement that recognizes the fact of patriarchy and “wants to abolish that state of affairs.” Morris and Withers emphasize the diversity of feminist efforts and their connection to social justice goals. Common demands in the 1960s were access to birth control, abortion, childcare, and gynecological health care, and the inclusion of women in historical research and history courses. Feminists used protests, conferences, teach-ins, and political lobbying to get their message across. They set up consciousness-raising groups, crisis centers, shelters for women and children, publishing houses, recording studios, and bookstores where women could be heard.

The next decade saw two significant gains. In 1972, the U.S. Congress ratified Title IX, outlawing discrimination by any educational program receiving federal assistance. Title IX has had an outstanding impact on women’s participation in sports at the secondary and college levels. In addition, abortion—which had been allowed (with several restrictions) in Great Britain since 1967—was legalized by the U.S. Supreme Court in its landmark 1973 decision, Roe v Wade. During the same decade, women boldly argued their cause in a profusion of books and magazine articles, theater and street performances, art exhibitions, dance shows, and musical celebrations. For example, the Womyn’s Music Festival, held in Michigan from 1976 to 2015, was the largest such women-only gathering on the planet.

Not surprisingly, women’s gains often prompted a backlash. The Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, first introduced in 1923, finally passed both houses of Congress 49 years later, but intense opposition by antifeminist lawyer Phyllis Schlafly and the ultra-conservative John Birch Society helped to defeat state-level ratification.

The Feminist Revolution shows how feminist strivings for social justice persisted, especially in three remarkable chapters: one depicting the energy and commitment of lesbian feminists; another showing the powerful conviction of African-American and Latina feminists; and a third illustrating feminists’ spirited opposition to militarism, nuclear arms, and war.

Organizing for lesbian equality had begun with Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon’s founding of the Daughters of Bilitis in San Francisco in 1955. Lesbians became more visible and vocal in the larger women’s movement in the ’60s, but they often found themselves marginalized by heterosexual feminists. For example, in 1969, Betty Friedan, president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), famously warned members against “the lavender menace” that lesbians posed for attaining NOW’s goals. (Her phrase spawned the formation of a radical feminist group called the Lavender Menace.)

Undaunted, lesbians went on to become leading figures in the women’s movement, among them poet Adrienne Rich, tennis champion Billie Jean King, and astronaut Sally Ride. Morris and Withers focus on the labors of less famous lesbians, too, such as the Combahee River Collective, a Boston-based movement in the mid-1970s that voiced opposition to “racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression.” With lesbian prodding, a NOW resolution of 1971 termed the oppression of lesbians a “legitimate concern” of feminism.

The Feminist Revolution shows African-American feminists fighting not only sexism but also racism, including from many white feminists. Black feminists made their voices heard, but it took extraordinary effort. A U.K. organization renamed itself the Abasindi Cooperative after a Zulu word meaning “survivor.” In the U.S., Rep. Shirley Chisholm became the first black person and the first woman to seek a national party nomination for president, campaigning in 1972 under the strident motto “Unbought and Unbossed.”

Some feminists were committed pacifists. Morris and Withers recall Jeannette Rankin, the congresswoman from Montana who helped ensure ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote. Rankin joined other legislators in voting against World War I, and in a vote taken after Pearl Harbor in late 1941 was the sole member of Congress to vote against war. In the post-war period, pacifist feminists protested military buildups and nuclear weapons in the U.S. and the U.K. In an astonishing photo from 1983, women from the U.K. Greenham Common movement can be seen dancing atop silos at the RAF Base Berkshire, at dawn, on New Year’s Day.

In the end, did these years of feminist struggle make a difference? Gender, race, and sexuality remain grounds for routine discrimination. In the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere, women lack parity in political representation, access to jobs, and pay, while reactionary crusades to nullify women’s rights, such as the right to abortion, continue. Sexual harassment and abuse go unpunished. Racist violence persists. LGBT people lack basic protection from discrimination in many states.

That said, developments such as the growing “Me Too” movement and women’s large-scale marches here and abroad are heartening. In that respect, The Feminist Revolution is a welcome reminder of the important gains that have been made, as its stunning material testifies to the undiminished spirit that women continue to bring to the work.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer living in Cambridge, Mass.