Published in: September-October 2014 issue.

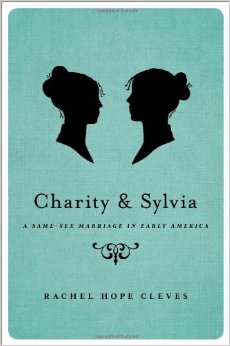

Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America

Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America

by Rachel Hope Cleves

Oxford. 296 pages, $29.95

IT IS EARLY 19th-century America. Two New England women come to live and work together for more than forty years. They are respected in their community for their excellent tailoring skills, for their industrious support of local church and town charities, and for their generosity to nieces, nephews, and assistants. Along the way, their business survives two serious recessions, while the couple survive eighteen-hour workdays and punishing popular remedies such as opiates, emetics, and bleeding. They are intimate, and inseparable.