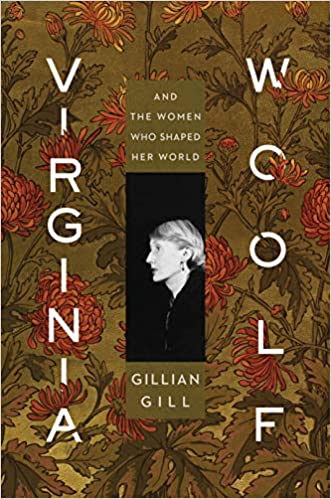

VIRGINIA WOOLF

VIRGINIA WOOLF

And the Women Who Shaped Her World

by Gillian Gill

Houghton Mifflin. 351 pages, $30.

IN HIS 1974 BIOGRAPHY of his aunt, Quentin Bell retells an anecdote that his mother Vanessa (née Stephen) Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, liked to tell to strangers: “The 20th century began at our Hyde Park home sitting room on a Spring day in 1904 when Lytton Strachey walked in and spotted a stain on my skirt. Semen? he asked.” Allegedly everyone present was sent into gales of laughter.

As this wisecrack reminds us, men were central to the Bloomsbury group, as Vanessa and Virginia and Lytton’s circle came to be known, a fact that Gillian Gill mentions often enough, even though the group is now better known for Virginia and Vanessa’s membership. The truth is, the men came together only because of the sisters’ older brother, Thoby Stephen, who wowed Cambridge with his beauty, strength, size (6’5”), athletic ability, and poise. These included the controversial bestselling author Lytton Strachey, economist of the century John Maynard Keyes, acclaimed novelist E. M. Forster, and the very model of a British modernist painter, Duncan Grant—all of them gay.

These are just a few takeaways from Gill’s marvelous, rich “family biography” of the Stephen girls and those around them. One surprise is a footnote about how William Thackeray’s lovers at Cambridge, two of whom lived fairly open gay lives in mid-Victorian England, agreed to burn his love letters from their university days once he became famous for Vanity Fair. Another is that Thackeray’s two daughters, one of whom became Leslie Stephen’s first wife, sold their father’s works to a publisher for £10,000 after his death—equivalent to $1.5 million today—and that all of the parties involved were satisfied they got a good deal. One daughter lived into her eighties and still left substantial sums to her nieces and nephews, including to Virginia, who used her inheritance to fund Hogarth Press, which she and her husband Leonard founded. These side facts may give a hint to how thorough and fact-filled Gill’s book is.

But if men play such a prominent role in this book, why has Gillian Gill given it the title that she has? Partly it’s because she’s the author of tomes on Agatha Christie, Mary Baker Eddy, Florence Nightingale, and Queen Victoria, so she and her publisher are presumably trading on her feminist credentials. Also, Gill really does spend much of the book dealing with some of the women who played a role in Virginia Woolf’s life. Not included are women like Vita Sackville-West and Ottoline Morrell, who might be thought of as Woolf’s connection to the lesbian world. Instead, Gill delves into Virginia’s ancestry, going all the way back to mad Mrs. Thackery on one side of the family tree and the Pattle sisters—belles of the Indian Raj—on another.

This strategy has the effect of displaying Victorian women in these families at their most memorable—and most mentally unstable—and also displays their social climbing acumen and their artistic genius (one relative was a pathbreaking photographer). It also serves to show how interrelated British society was, even beyond the nobility, in the class that Gill identifies as the Haute Bourgeoisie. This interconnectedness is apparent in the wonderfully vivid black-and-white photos of the “beautiful Pattle sisters” and the portrait of Thoby Stephen from sixty years later. The contrasts of extreme beauty and extreme instability were very much a part of Virginia Woolf’s birthright. That she managed to live her own life and produce such an abundance of great writing is much to her credit, and much to our good fortune.

This strategy has the effect of displaying Victorian women in these families at their most memorable—and most mentally unstable—and also displays their social climbing acumen and their artistic genius (one relative was a pathbreaking photographer). It also serves to show how interrelated British society was, even beyond the nobility, in the class that Gill identifies as the Haute Bourgeoisie. This interconnectedness is apparent in the wonderfully vivid black-and-white photos of the “beautiful Pattle sisters” and the portrait of Thoby Stephen from sixty years later. The contrasts of extreme beauty and extreme instability were very much a part of Virginia Woolf’s birthright. That she managed to live her own life and produce such an abundance of great writing is much to her credit, and much to our good fortune.

Quentin Bell’s Virginia Woolf: A Biography, which Gill rightly credits with the Virginia Woolf revival of the past half-century, contained other revelations that she seizes upon. The most infamous is the fact that Vanessa and Virginia were both molested as pre-teens by their half brothers, George and Gerald Duckworth, who were a decade older. Bell and Gill believe that this had less of an effect on Vanessa, who quipped that her first orgasm occurred at the age of two, than it did on Virginia, who experienced lasting effects. The author presents much evidence to support her claim that Virginia and Leonard ended copulation soon after the first year of their long marriage—and that Leonard never had sex with his second wife at all!

Vanessa, whose more-or-less heterosexual but widely gallivanting husband Clive Bell gave her two sons, led a far more sensual life. This included roping in Duncan Grant, with whom she was in love, for at least one sexual encounter, which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Angelica Bell. This happened while Duncan had a male lover living in the same house along with Vanessa. John Lehmann, freshly “down from Cambridge.” was another beauty, nicknamed “Bunny,” who seduced and then married Angelica some twenty-odd years later.

If you think you need a score sheet to keep it all straight, you’re right. So take note that another Pattle heiress, the once beautiful Julia, Leslie Stephens’ second wife and the girls’ mother, was the woman who arguably had the greatest influence on the Stephens women. Vanessa reacted by rebelling against most social constrictions for an entire life of 84 years: a painter in Bohemia with a private life that no one could possibly imitate. Virginia married a Jewish man, became a blue-stocking, and then became a famous writer. She admitted to Vanessa that she could only love other women romantically—all of which would have shocked and disgusted their (literally) straitlaced mother had she been alive to witness it.

Both girls had watched not only their mother but also their half-sister Stella Duckworth wear themselves out and die young by doing everything they possibly could for others while neglecting themselves. Clearly neither younger sister would fall for that. Virginia’s early independence came by way of her writing for the Times Literary Supplement, which she did all her life. Her early reviews were of books that male critics disdained but that had wide appeal to women readers. She went on to write brilliant book reviews and essays issued in small books, such as The London Scene, The Common Reader, and especially A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas. The latter two are feminist classics laying out the simple but essential, even revolutionary, idea that women need spaces and deserve resources of their own. If you’ve tried Woolf the novelist with no luck, try her essays, now collected in four fat volumes. They are among the best nonfiction of the last century.

While many think of Woolf’s fiction as wildly experimental à la James Joyce, citing The Waves and To the Light House, or as requiring a mastery of unusual points of view, as in Flush (a dog’s point of view) and Orlando, much of her work is quite accessible. For starters, I would recommend Jacob’s Room, her brilliant and loving short novel about a young British man very much like her brother Thoby. Gill doesn’t discuss those works. Nor does she discuss Woolf’s same-sex relationships and whether they were platonic or sexual. Others have already written those books. What she presents is a thorough, fascinating, and largely uninvestigated ambience for understanding some of Virginia Woolf’s life and psyche.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).