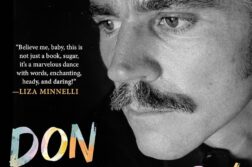

NOW in his eighties, Charles Rowan Beye holds the title Distinguished Professor of Classics Emeritus at Lehman College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Beye is better known to the world as a translator of the ancient Greek classics and as a scholar whose books include Odysseus: A Life (2005) and Ancient Epic Poetry: Homer, Apollonius, Virgil (1993). He has now written a memoir about his life and work titled My Husband and My Wives: A Gay Man’s Odyssey.

The new book is a personal testament to the unpredictability of human nature and sexuality. In 2008, Beye married his longtime partner Richard at a chapel on the edge of the Harvard University campus, where he had received a doctorate in classical philology nearly fifty years earlier. Beye’s stated goal in writing his memoir was the hope that, upon conclusion, it would leave the reader “with a better understanding of the obstacles and shoals the gay male must navigate just to grow up and assume the responsibilities of adulthood.”

As an expert in the Homeric and Virgilian epics, Beye knows instinctively how to spin a good yarn. In his quest for self-discovery, and his own personal Eros, he looks to the ancient model to make sense of his own experience. Although a sexual maverick over time, Beye suffered during puberty and into adulthood from a sense of guilt

instilled in him by his Christian (Episcopalian) upbringing. A childhood fall off a balcony, which damaged his lower back and forced him to wear a corset and brace until he was eighteen, left him on the school sidelines at Andover: “My schoolmates were a congenial lot, but I was not part of their athletic program, which is the true glue of teenage male relationships.” However, this turned into a sexual jackpot for the fourteen-year-old outsider, as he was placed in a dorm for the older beginning students, where each had his own room: “a lucky stroke, as it gave me the privacy to experiment sexually, without fear or shame.” This included orally pleasuring many of his horny (straight?) fellow students. Beye jokes that his first title for the book was “Blowjob: An Iowa Boyhood.”

It is difficult to decide whether Beye’s precipitous jump into heterosexual marriage, not once, but twice, was prompted by pure lust or an unconscious bid for conformity and social acceptance (or both). Perhaps it was “Fate,” a recurring leitmotif in this memoir, one that also relates to Beye’s lifelong refutation of Christianity and all its dogma, and to his embrace of all things Greek. Following his bliss into the avid study of Greek classics helped Beye “to forge an aesthetic, ethical, and moral system to take the place of the Christianity I discarded.”

The attempt to juggle marriage, raising children, forging an academic career in an institutionally straight old boy network, and falling in and out of gay relationships proved too much for Beye, and he experienced a breakdown during his last term at Yale. (The triggering event seems to have involved a drunken Beye groping a classics student after a graduation party.) He voluntarily admitted himself for a stay in the Grace-New Haven psychiatric ward.

Beye’s long life has indeed been an odyssey, as promised in his subtitle. To be sure, there are times when Beye comes off as the stereotypical absent-minded professor, times when he seems too needy or narcissistic. But in the end his honesty and open-mindedness trump everything else, and the upshot of his story is a life-affirming one.

In an interview conducted through e-mail, Beye shared his insights about same-sex relationships in classical Greece.

Michael Ehrhardt: In your memoir you’re heroically frank about your sexual exploits. How do your family and husband feel about that? Charles Beye: My husband has never expressed an opinion on the matter; but I know that he thoroughly supports the material that I’ve included in the book, since he read it many times during its gestation. One of my daughters read the manuscript with great care, and has recommended it to all her friends in a very Christian community. (She’s studying for the ministry.) My other daughter, I’ve been told, is offended enough not to want to read the text, but she claims she intends to send a copy to her eighty-year-old-mother-in-law, and hopes “she can get past the blow jobs.” One of my sons sent me a very warm commendation for the style and content. However, my other son and his family, who are all Midwestern Christians, made no comment. My very conservative son-in-law, in his own quiet way, said it was great—which quite surprised me. My siblings, all in their eighties, are very supportive, although, one nephew declared that his mother was horrified. ME: You say that as a teenager you didn’t identify as being gay, that you thought sex with other males was perfectly normal. How was it that you weren’t ostracized at school? CB: That’s an amazing thing. At Andover I had sex with two students, independently—one didn’t know about the other—and they never said boo. I had no sense that it was socially disapproved. Yet, when I had sex with boys in high school, who were lower-class boys from parochial school—when they all started talking, then my reputation went down. They were more hostile. It was a nightmare. The subtitle “a gay man’s odyssey” gave me pause when I suggested it, and in some ways it seems to me to be inhibiting. When I say “I am gay” I mean only that I am sexually attracted to other males. I bring all this up because the word “gay” in some people’s mouths or minds means something cultural. I consider myself gay because that is the term in common parlance to describe a male who is sexually attracted to other males. I do not consider myself to be bisexual, whatever that may mean, because, although I have had entirely satisfying and long-term sexual relationships with two women—fathering four children with one of them and helping to raise them into their late teens—I know myself to have been far more immediately sexually attracted to males. ME: The ancient Greeks had a whole different take on same sex liaisons. The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is a key element of the myths associated with the Trojan War. Its exact nature has been a subject of dispute in both the classical period and modern times.What was exactly happening between Achilles and Patroclus in the tent? CB: I do not for one minute believe that Patroclus and Achilles were having sex. It’s not to say that, in later times, we have a fragment of a play by Æschylus in which Achilles talks about yearning or lusting after the thighs of Patroclus—or maybe it’s the other way around. Which suggests they were quite close friends. But it’s not Homeric. Also, I doubt that an active erotic component would have occurred to the Greeks of an earlier age. In the Iliad, the poet describes the two men going to bed in the same tent on opposite sides, each with a concubine, or comfort woman. at his side. Patroclus’ girl is described as being a gift from Achilles, which we moderns find to have a homoerotic coloring to it. ME: Since you’ve studied the Greek New Testament, have you ever come across a specific condemnation of homosexuality? CB: As I recall, that asshole Paul, in the first letter to the Romans, condemns same-sex relations, but as the experts all insist—or some of them anyway—he was talking about paying for sex with a boy, not about doing it with a socially equal chum. Oh, who knows?! It’s all such gibberish, anyway! ME: Gore Vidal always rejected the terms “homosexual” and “heterosexual” as inherently false; that “we are all bisexual or pansexual to begin with.” It’s the truth of our condition. Apropos the classics, doesn’t that square handily with the satyric theory of Aristophanes in the “Symposium”? CB: Yes, but if anybody was an old queen, it was Gore Vidal, despite making that claim ad nauseam. In truth, Aristophanes never actually said that, of course: the Platonic dialogues, in one sense, are what we might call a novel of ideas, and the Symposium is one chapter in that novel, which is all created by Plato, and comes out of his head, despite whether or not any of the participants might have happened to say what is put into their mouths. And here Plato is advancing a complicated idea of the Ideal. Along the way he has Aristophanes make the speech about the two halves. And, yes, the culture of the time made it easy for Plato’s readers to imagine two men lying naked in bed, humping each other, trying to become One again, because the culture permitted males to think that way and act on their desire. Plato’s Aristophanes, and the two halves, speaks to the inherent narcissism in males who, culturally speaking, are made to feel that they own the world. Therefore, fucking another male is sublimity, since it is indeed the union of two bits of perfection. ME: Doesn’t Plato’s Symposium seem somewhat murky on Athenian law regarding pederasty? CB: Sometimes, people note that Plato—in the Laws—speaks out against homosexuality. This is in contradistinction to the positive spin put on the practice by most ancient Greek city-state cultures. First off, one should remember that Plato was an individual who wrote a series of treatises that had a limited circulation and appeal in his own time. It was not until much later, in the Hellenistic period, but even more in the second century CE, that Plato’s ideas were widely disseminated. (Of course, they were used by early Christians as a cloak for their beliefs in order to make them more palatable to Gentiles.) The objection one does encounter derives from the idea of the responsibility of both genders to procreate in order to sustain the society, subject as it always was to loss through disease, accident, and war. Marriage was more or less obligatory in several societies. Male–female relationships were valorized because they alone produced issue. Homosexual relations which produced nothing were deemed to be simply for pleasure, and Plato objected to that because there was no “duty” involved, and it produced licentiousness. Among the Romans, while the sexual attraction that younger males exerted on their elders was considered perfectly normal, the Romans forbade the kind of intergenerational male erotic relationships that the Greeks enjoyed, insisting that only males of the prostitute class could be enjoyed for sexual purposes. A pederastic emotional relationship between two freeborn Roman males was unthinkable. Among the Greeks, evening drinking parties where there was considerable pederastic action were a feature of the aristocratic class. As time went by, it grew more politicized and ostentatious as the aristocracy sought to distance and distinguish itself from the emergent bourgeoisie. One can almost see it as the distinction of upper-class English schoolboys and their erotic behaviors and the disapproval of the clean-cut middle class. The older man caressing the beardless youth at a symposium reflects the classical Greeks’ approval of the amatory relationship between men and boys in their late teens, which they considered to be a cornerstone of a cohesive society and a strong military posture. ME: Is Ganymede—the beautiful youth abducted by Zeus to be his cupbearer—an archetype of the Greek pederastic tradition, proving that even the gods can’t resist a toothsome shepherd? CB: Zeus is a male as well as a god. As a male, he is subject to the same needs that move humans. The Greeks conceived of gods as having all the same physical and psychic needs as humans, with the one supreme difference: they were immortal. So, Zeus as a normal male would have a strong erotic interest in good-looking teenage boys. Because of his power, he could come along and take them off, whether by seducing them with bribes of treats, money, or whatever, or just by sweeping them up and off. There’s no doubt but that in the early period when social controls like police were nonexistent, powerful men could steal away to their abodes any boy they found. I’m sure that in the economically depressed areas of the world today, one can buy young boys and girls and keep them for sexual pleasure. Ganymede is a story that has been prettied up, but the underlying truth is grim. ME: What exactly was the motive behind Socrates’ condemnation to death for “corrupting” youth? CB: That has to do with the trumped-up charge of his being an atheist, or at least not believing in the same gods as the citizens of the city state. The notion that he was corrupting the youth in some sexual way is not anything but tradition and is nonsense. ME: Do you believe that the policy of “Don’t ask, don’t tell”—now happily dismantled—could have been disproved earlier from the knowledge of the ancient Greek concept that there were distinct military advantages to the employment of male-male lovers, such as the Sacred Band of Thebes? CB: No. We are basically a Christian society, and the story of the Sacred Band is anathema to most Americans. The legacy of classical antiquity has to be heavily sanitized to be taught and understood in this country. ME: In Euripides’ Bacchae, Dionysus is portrayed at times as an effeminate Eastern influence. Did the Greeks recognize androgny as effeminacy? And was it anathema to them? Is Pentheus’ dressing in drag considered a shameful demasulinization or just tragic irony? CB: The Athenians, and the Spartans more so, were keen on an appropriately vigorous male military posture, if for no other reason than the Spartans needed to control a land filled with slaves, and the Athenians to police the empire they had created in the Ægean. So tough, aggressive stances, while not to be overdone, were nonetheless more the ideal for the adult male. The relaxed, more openly sensuous, more yielding physical behavior of males in the land mass of present-day Turkey they saw as more girlie. It is a kind of behavior that controlling, need-to-dominate type males find challenging, often frightening or at least dangerous. And Euripides is playing into that in his Bacchae. The transvestitism suggests, more than anything else, the way the Pentheus has become de-natured, possessed by a foreign element. It would be like seeing our nation’s leader coming out for a press conference completely stoned, in cut-off jeans, pony tail, and tattoos. I think Athenians looked upon Persian or Eastern dress and manners much the way men in the American Midwest might react to the dandified, elegant, flirtatious, stylized mode of behavior of Italian males. ME: I was surprised to learn that even in avant garde France, gay marriage is hitting opposition. The same tired old debate lingers on. CB: The Roman Catholic Church is the great enemy, and always has been. It is grotesque to see it wielding that power after the secularization of the French state, after their sordid part in the Dreyfus affair, in the deportations of the 1940s. Theirs is a squalid history. But, as Necker said to Marie Antoinette, and truer words were never spoken: “Le peuple, madame, c’est une bête. Michael Ehrhardt, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in New York City and New Jersey.