David Bowie Is

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

March 23-August 11, 2013

David Bowie Is (Catalog)

Edited by Victoria Broackles and Geoffrey Marsh

V & A Publishing. 288 pages, $55.

WHETHER you’re a Bowie fan or not, chances are you’ve heard about the sudden return of the Thin White Duke in the form of an album, The Next Day, released in March, which Bowie had been recording in New York over the previous two years, along with three (to date) promotional videos. The first of these accompanied the single announcing the comeback Where Are We Now? Released without fanfare on Bowie’s 66th birthday on January 8th, it received extraordinary global press coverage, overwhelmingly positive, about everything from the melancholic cadences in the singer’s vocal performance to the thematic return to the Berlin of Bowie’s acclaimed trilogy Low (1977), Heroes (1977), and Lodger (1979). These are the albums in which Bowie began experimenting lyrically with the “cut up” technique devised for prose fiction by Brion Gysin and William Burroughs. They were also produced, like The Next Day, by Tony Visconti, who—in the absence of any public comment from the performer—has unofficially acted lately as his “voice on earth.” The album sleeve, with its overt referencing of that of Heroes, might likewise suggest an instruction to overlook three decades of Bowie’s subsequent career.

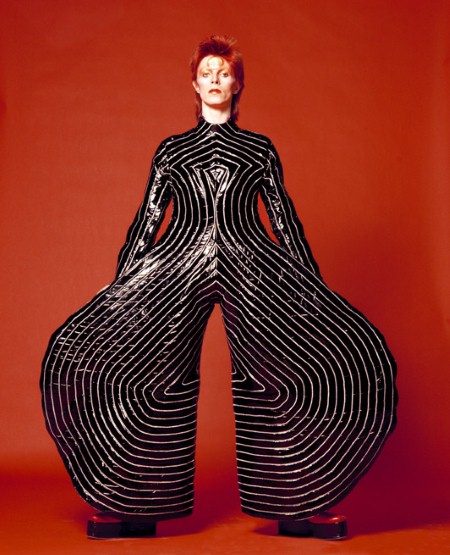

Scottish actress Tilda Swinton—who appeared in the video for the second single, The Stars (are out Tonight)—opened the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum’s David Bowie Is exhibition, giving a slightly surreal dinner speech, addressing the absent singer: “When I asked you if you wanted me to say anything here tonight, you said: ‘Only three words, one of them testicular.’” Bowie, it had seemed and been reported, was indifferent to the Victoria and Albert’s plan to raid his wardrobes, cupboards, bookshelves and photograph albums. Whether this was true or not, he had allowed the curators full access—and, apparently, free choice as to what to display. A more cautious figure might not have welcomed the inclusion of one ’70s fixture, for instance: an elegant cocaine spoon.

Richard Canning’s most recent publication is an edition of Ronald Firbank’s Vainglory for Penguin Classics (2012).