IF YOU’RE PLANNING to be in New York City at any point this winter, there’s even more reason than usual to get to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met has two huge exhibits this winter with substantial gay themes. The first, Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer (Nov. 13, 2017–Feb. 12, 2018), is the largest Michelangelo exhibit in the museum’s history. The other is a retrospective of David Hockney’s work titled simply David Hockney (Nov. 27, 2017–Feb. 25, 2018).

There is a lot of art in the Met on LGBT themes, but the museum usually hides it as well as it can. As an example, one of the high points of the Met’s 19th- and early 20th-century European painting collection is the masterpiece of the great animal painter Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair (1853). Bonheur was a lesbian and a cross-dresser; perhaps today we might say she was genderqueer, though it is hard to interpret the meaning of cross-dressing for women in earlier centuries, when women’s attire (and lives) was so tightly controlled. In any case, Bonheur places herself, dressed as a man, right in the middle of the canvas, looking out at the audience with what might best be called a smirk. This was pointed out in the 1980s by a pioneer of gay art history, James Saslow, who notes that this figure’s face closely resembles many other portrayals of Bonheur. Still, thirty years later, the Met still chooses not to acknowledge it on its label, as if this fact—surely the most intriguing thing about the painting, otherwise not to the taste of most modern viewers—were not interesting at all.

But with this winter’s shows, art at the Met is suddenly coming out of the closet! Both are very open about the artists’ sexualities and the homoerotic themes in their work.

You might wonder if we can call Michelangelo “gay” in the modern sense, but clearly he was a man with strong attractions to other men, and the homoerotic is important in his work, including his poetry. The Met show encompasses works with explicit connections to his gay side, and the labels about them discuss the issue clearly. For instance, the show contains the best remaining copy (by Giorgio Giulio Clovio, 1530s?) of a famous work that has disappeared, a drawing of Jupiter in the form of an eagle carrying off his boy-toy Ganymede, which Michelangelo gave as a gift to his great crush (I’m not sure one can say more), the Roman aristocrat Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, for whom he also wrote some of his most passionate love poems. The show includes a number of works created for de’ Cavalieri, as well as a drawing (1531-4) of another of Michelangelo’s crushes, Andrea Quaratesi. Again, the show’s materials mention the nature of their relationship frankly.

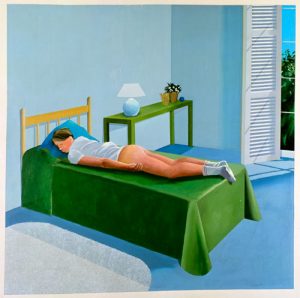

David Hockney is an artist of our own time. Being openly gay and making openly homoerotic work was important to him from early in his career—even when gay relations were still illegal in the UK—and this retrospective is replete with gay themes. It contains early works into which Hockney slipped what he called “gay propaganda,” nudes inspired by beefcake magazines, portraits of gay celebrities (such as Christopher Isherwood, W. H. Auden, and Andy Warhol) with whom the artist socialized. I happen to love Hockney’s nudes for their combination of eroticism, folksy simplicity, and campy irony, and I was thrilled by the opportunity to see works like The Room, Tarzana (1967).

It seems otiose to say it when talking about Michelangelo and Hockney, but I highly recommend these shows, and a winter visit to the Met in general! [Note: The Hockney show is slated to be covered in depth in the March-April 2018 issue of The G&LR.]

Andrew Lear is the founder of Oscar Wilde Tours.