OF ALL THE THINGS that Paris is famous for—the historic neighborhoods, the amazing museums, the spectacular food—what’s often overlooked is Paris’ importance in LGBT history and culture. France was the first modern country to decriminalize homosexuality—in 1798, almost two centuries before the U.S. From that time on, Paris has remained a relatively free city for gay life, and gay themes appeared more and more openly in French culture over time. This is why there are so many great gay writers in French literature, including names like Proust, Cocteau, and Colette. It is also why so many gay writers from English-speaking countries spent large parts of their lives there, including Oscar Wilde, Gertrude Stein, and James Baldwin.

In fact, gay history is a great theme to follow around Paris—a good way to organize a short visit. There are numerous places where you can follow gay history’s trail. Across from the Louvre, the Palais-Royal has a lot of gay history. Among other things, it was the Paris residence of Louis XIV’s gay (or perhaps bi) and gender-bending younger brother Philippe I, Duc d’Orléans (generally known simply as “Monsieur”). It is also here that Colette lived for the last two decades of her life and produced her most interesting writing about lesbians (1932’s The Pure and the Impure) as well as her best book on her other favorite theme, courtesans, Gigi (1944). But there are two places in Paris that, in my view, make for the richest gay history experience: the Louvre and Père Lachaise Cemetery.

To start with Père Lachaise, which really shouldn’t be missed. First of all, it is a very charming old cemetery and has wonderful views of Paris (because a large part of it is on a hill). And it contains the graves of an amazing variety of famous people. Whatever you’re interested in, you can find people that matter to you at Père Lachaise. For opera queens, for instance, there are the graves of Rossini, Bellini, and Maria Callas—and also Edith Piaf. Gay history is also very prominent, as Oscar Wilde is probably the cemetery’s most famous denizen (aside from Jim Morrison?). It is also quite well-known that Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas’ joint tomb is there. But there is plenty more, including Proust and Colette, and also 19th-century artist Rosa Bonheur. A name that few readers may know is that of Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, but he was an important person: arguably the forefather of gay liberation. Cambacérès was a gay aristocrat who survived the Revolution and became second consul under Napoleon. He was one of the key authors of the Code Napoléon—the law code that forms the basis for French law today as well as law in many other European countries—and it is generally believed that he is responsible for the fact that the Code followed the Revolutionary law code in leaving out homosexuality, even though many people wanted laws against sodomy to be reintroduced.

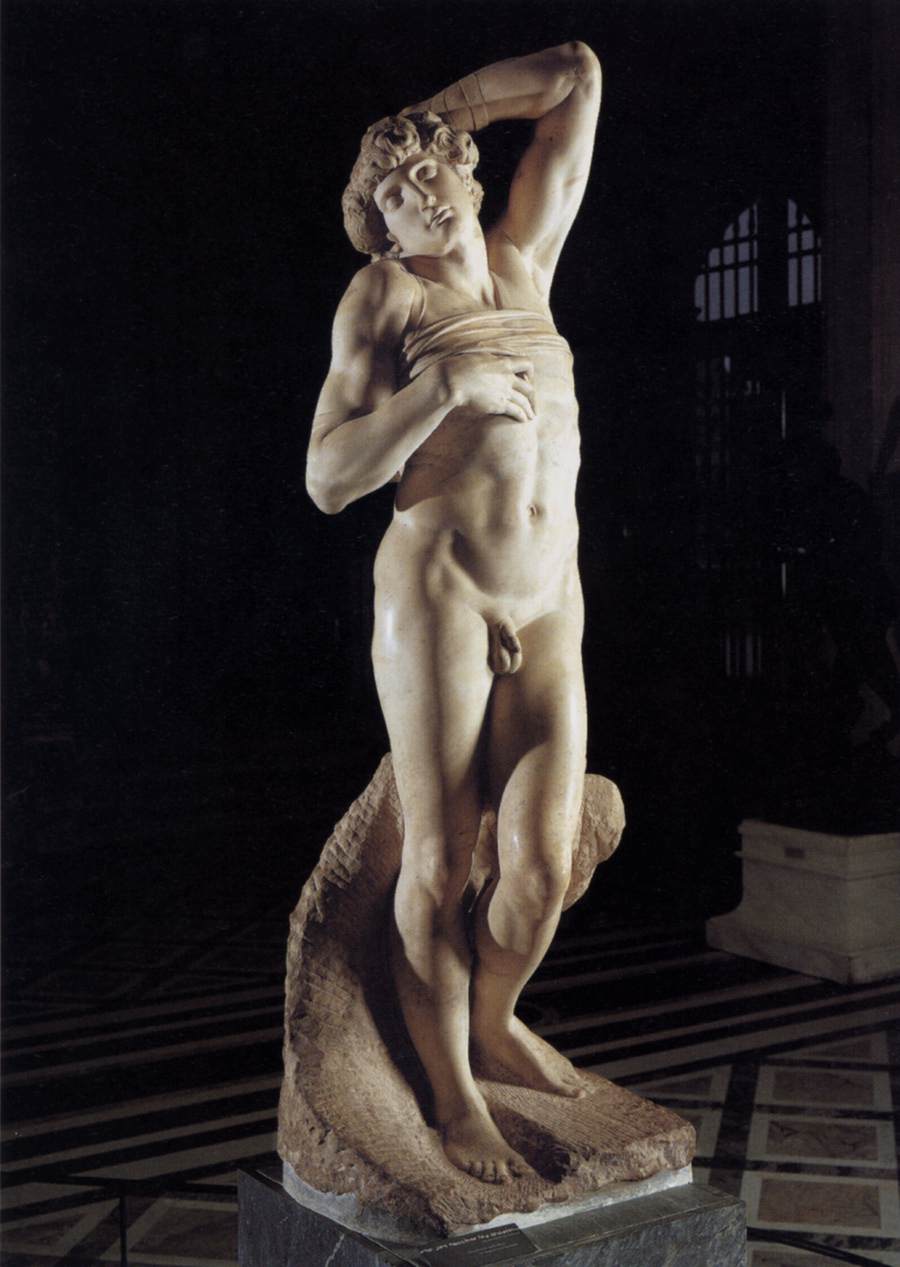

The Louvre, of course, is an astonishing museum—and an astonishingly gay one. One reason is that it has such important collections from ancient Greece—where some forms of same-sex love were considered praiseworthy—and ancient Rome, plus the Italian Renaissance. The Louvre’s massive Greek vase collection is particularly rich in homoerotic themes, as are its Roman and Italian collections. For instance, it has not one (like the Met) but four busts of Emperor Hadrian’s boy-toy Antinous, who was declared a god after his death. And it has homoerotic works by the two biggest gay geniuses of the Renaissance: Michelangelo’s orgasmic-looking Dying Slave and Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist, portrayed as a sexy youth and modeled on Leonardo’s favorite (though difficult) assistant, a boy he nicknamed “Salaì” (little devil). Indeed, one should probably also include the Mona Lisa in this category, as some scholars think it was at least in part modeled on Salaì as well.

And the homoerotic side of the collection continues into later ages, including a number of strikingly homoerotic works from Revolutionary and Napoleonic France—works in which the artist used the prestige of the Classical civilization to express homosexual themes. For instance, in the French sculpture collection, there is an 18th-century statue of the gay couple from Virgil’s Aeneid. This is a fascinating work, because there was no ancient model: the 18th-century sculptor was obviously so taken by their tale of heroism (in which one dies protecting the other—just the kind of story the Greeks and Romans loved) that he invented an ancient artistic model. And in Jacques-Louis David’s vast canvas of the Spartans at Thermopylae (a battle people today know from the movie 300), David puts in the kind of heroic couple so widely praised in ancient Greek literature, in which the younger man admires and encourages the military valor of his older lover.

The Louvre is effectively endless, so it’s fun to have a secret trail to follow through such a vast collection. When I lead such a tour of the Louvre, we don’t neglect the standard highlights, but the gay organizing principle helps us to see all the works in a new context. The Louvre is one part of the Paris trip that I lead with Oscar Wilde Tours. This summer I’ll be leading a trip with Out Professionals – open to all – from July 27th to July 31st. To find out more about this trip, click here.

Andrew Lear, a classicist and an art historian, is the founder and head of Oscar Wilde Tours.