In the same decade that the trial of Oscar Wilde and the network of male brothels on Cleveland Street swept the headlines and flamed a push for a tougher stand on anti sodomy laws, an English artist thrived by openly celebrating the beauty of the male body. Victorian morals had more ambiguity and space for contradiction than the traditional vision of a Puritan, more conservative age.

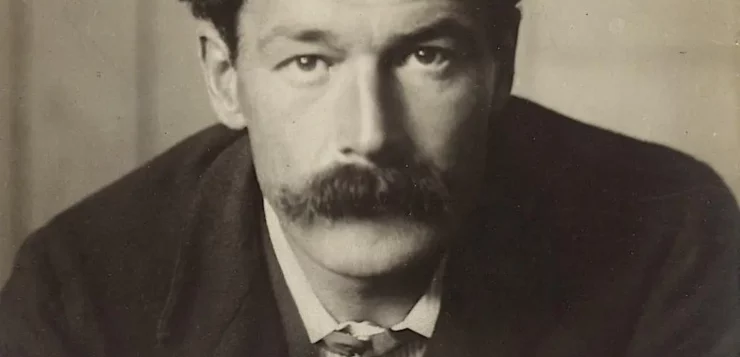

H.S. Tuke (1858-1929), the Impressionist painter son of a prominent Quaker family, benefited greatly from these vague boundaries between what was considered depravity and what was art. Although no record exists of him being gay, he actively participated and was friends with an intellectual circle of homosexual literary men, such as John Addington Symonds. They, in turn, were influenced by Tuke’s paintings, such as those of youthful male nudes not set in biblical or historical narratives, but simply basking in the sun, bathing indolently on rocky coves of the Cornish landscape, or sailing playfully in boats.

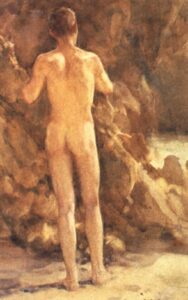

The most striking aspect of his style was a vivid palette of Mediterranean blues and the way in which he captured the effect of sunlight on the pale skin of his boyish subjects. Always pale, of ivory flesh, russet tan, and an athletic, slender build like the one from marble statues of Greek youths. Tuke seemed to place his bathers in a dreamland that, with radiant sun and sparkling emerald seas, evoked the ideal Arcadian past where several homosexual artists imagined the “love that dare not speak its name” flourished, unimpeded by austere morality.

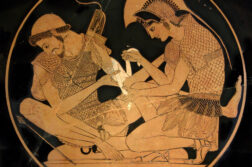

Tuke was a favorite of the group of poets known loosely as Uranian, so-called in namesake of Plato’s description of two loves in The Symposium. The traditional one guided towards reproduction and the one of Uranian Aphrodite, a love between men, which was considered in Greek times to be of a higher spiritual value because it came to be not just out of lustful instinct, but also an interest in the intellect and wisdom of the partner.

This informal Uranian movement, a Victorian intellectual network of homosexuals related to figures such as Symonds, Wilde, Baron Corvo, and Charles Kains Jackson, saw in Tuke a manifestation of their Hellenic idealism. Antiquity represented a utopia where relationships between men were accepted not in the name of individual sexual rights, but as a desirable aspiration of society, an ethical practice that promoted comradeship and stronger bonds of affection between the soldiers and aristocrats of the polity.

British homosexuals turned to Greek history and mythology to talk about their forbidden desire in a non-reprehensible manner. References to the Classics were valuable currency to the Victorians. Hellas was considered the cradle of Western civilization; the ancients were the solid base of philosophy, political theory, and even aesthetics, having achieved the highest refinement in sculpture, theatre, and poetry. Male beauty could be openly celebrated if the object of one’s desire were the young shepherds, ephebes, or heroes of Greek tradition like Ganymede, swopped to the heavens by Hylas, the lover of Hercules who was tragically drowned by lustful nymphs.

The warrior ideal also embodied certain elements of Greek homosexuality which highlighted the defense of such love. The bond between the brave Achilles and the faithful Patroclus was fairly known, as was the assertion of Phaedrus, again in the Symposium, that an army composed of lovers was desirable since each man would be more obliged to die for his companion in the battlefield. The focus on this vigorous and militant aspect of gayness was perhaps a way to counter the notion that men who loved other men had fallen in some sort of degeneracy that led them to become weak and effeminate.

Tuke´s work rarely contained overt allusions to this extended Hellenism (although there are paintings of a Hermes and a Cupid), but his sunny atmospheres, azure, crystalline seas, and lean, youthful, pale models placed in timeless landscapes gave, as Symonds put it “an aura of antiquity.” There is an understated desire in his canvases that makes them ambiguous, unlike in, for example, the photographs of a Von Gloeden there are no exposed genitals or poses that suggest plainly sexual intention in Tuke’s work. There are instead distracted gazes, his models lost in thought, suggesting an introspection that invites the viewer to be interested in beauty and its contemplation. His paradisial visions of never-ending sunshine over smooth limbs are removed from the more sombre reality of an England where homosexuality was proscribed by law.

Tuke does away with the distracting togas and awkward laurels placed in other nineteen century montages of youth that attempted to capture the spirit of Greece. Armed with intense impressionist tones and an unmatched chromatic talent where the golds and blues perform a vibrant symphony, he captured unfading beauty and enticed homoerotic interest in his work.

After his death, and despite a fruitful career that included entry into the Royal Academy in 1914, both Tuke and his work slowly faded into obscurity. Because his figurative paintings were not compatible with the abstraction of the modernist vanguards, Tuke was relegated to the category of a second-class beach painter. Not until the end of the twentieth century were his bathing youths seen under the new light of the so-called “queer gaze,” and his talent appreciated as more than the one of a copycat French impressionist. Tuke´s originality in portraying male beauty in a Victorian context was that, although drinking from the fountain of Hellenism as his contemporaries, he did not constrain himself in displaying homoerotic beauty as a relic of the long-lost past. His work has notes of melancholy for the past, yet still aspires for immortality in all ages.

Samuel Muñoz is a history student from Bogota, Colombia with an interest in gay art and literature.