Books, books, books: in my home office they are double-shelved in bookcases and stacked in sub-groups on most other surfaces. Researching over several years of what became Inside the Spiral: The Passions of Robert Smithson (University of Minnesota Press), I became confined by piles of books. But those volumes expanded the book I wrote from a biographically-informed monograph to a psychological study of both artist and art, which became the first biography of Robert Smithson. The experience of being engulfed in books is common to those in the humanities who are immersed in their research. But here is my difference: I have a library within a library, and it replicates my subject’s. Reading books that were in Smithson’s collection revealed characteristics he had kept under cover.

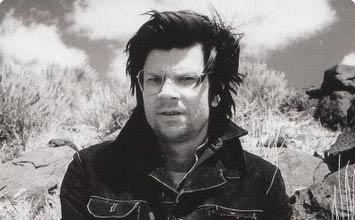

Robert Smithson (1938-1973) has been acclaimed for his sculptural innovations and verbal agility. His most famous creation became the icon of Earthworks, the Spiral Jetty (1970), a fifteen-foot-wide, fifteen-hundred-foot-long curving path of earth projecting from an edge of the Great Salt Lake. But his legacy stems more from his writings and interviews advocating for an expansive view of the art object than his sculptures. A sculpture could be a rock-filled low bin that he termed a “non-site,” its shape linking its geological matter to its distant source, the “site,” also represented by snapshots and a map. In other words, the meaning of art derived from all sorts of relations, rather than being an autonomous thing in itself.

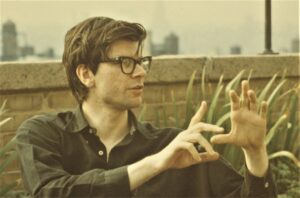

Smithson did not attend college, unusual then among ambitious young sculptors; Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Richard Serra even had master’s degrees. Instead, his library was his university. Among the pals he debated at Max’s Kansas City Restaurant & Bar, or with whom he crossed the Hudson River on jaunts to New Jersey quarries, he was known as an “autodidact.” Fellow artist, onetime co-author, and regular drinking buddy Mel Bochner described him as “A polymath, in command of a prodigious range of sources. Wickedly, brutally, bitterly, laugh—out—loud funny, he could turn any situation, any discussion, upside down with a withering aside, punctuating it one of his darkly perverse chuckles.”

It is not surprising that Smithson owned many books, but it is unusual among visual artists that the contents of his copious collection is known, having been inventoried soon after his death at 35 in a plane crash. Smithson owned roughly 1,120 books (several additional titles that he referred to in print or interviews were not found in his possession). If one arbitrarily considers his years of book acquisitions as from when he was fifteen to his death twenty years later, his acquisition (and retention) rate averaged 56 books per year.

When researching a biographically contextualized monograph on Smithson, I mined this resource. I attempted to read not just the same words, but the same format and publisher, and to see the vintage book covers. The most intriguing were those incongruent with his reputation as being intellectually sophisticated – ‘cooly cerebral’ – and mockingly sardonic. Inside the Spiral includes a bibliography of books Smithson owned in subject areas that he did not draw attention to by epigraphs and references, such as writings by early saints, including those on alchemy, astrology, mysticism, and The Black Arts (1967) in addition to books by authors whose writing manifests their Catholicism, a number of whom had converted to it. Eight books have ‘self’ in the title; two are The Self in Psychotic Process: Its Symbolization in Schizophrenia (1953), and The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness (1959).

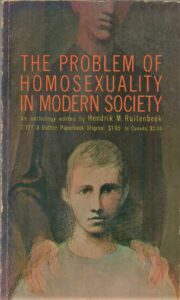

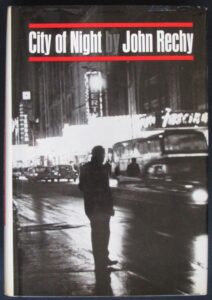

Those titles’ implications of an identification with a divided self gives insight to his numerous books on what was – especially then – outré sexual practices. He and his wife, Nancy Holt, who in the course of their marriage transitioned from being a biologist lab technician to a vanguard sculptor, made it appear that they were closely bonded. She typed and edited his texts, hosted dinner parties, accompanied him on exploratory trips, collaborated with him on films, and worked closely with him on his professional ascendance. So, the most discrepant – and conspicuous – indication of a hidden or divided self is the strong presence of books on homosexuality. The year Smithson and Holt married with a Nuptial Mass in a grand uptown Roman Catholic church, 1963, is also the publication year of John Rechy’s novel about gay male hustlers, City of Night (Smithson also owned Rechy’s follow-up Numbers); of the surrealist poet Michel Leiris’ autobiographical Manhood: A Journey from Childhood into the Fierce Order of Virility, written about a self-abnegating young man; and of the anthology The Problem of Homosexuality in Modern Society.

Smithson owned a first English language edition of the seventeenth-century Catholic tract Peccatum Mutum: The Mute [or secret] Sin (1958) – which was considered an unspeakable account of sodomy. The author is Ludovico Maria Sinistrari, a Roman Catholic priest and an expert on demonology and sins relating to what was then considered adverse sexuality, specifically the sinful act of anal penetration. “This crime is exceedingly heinous . . . because the engendering of man is prevented, so long as the seed is poured out in a barren place, where it can have no chance to grow.” Sinistrari advocated punishment for sodomy as torture by fire – that is, at the stake in this world, not the eventual conflagration below. Other titles Smithson owned also suggest a troubled relation to sexuality: Auto-erotism: A Psychiatric Study of Onanism and Neurosis (1950), and psychoanalyst Theodor Reik’s Psychology of Sex Relations, (1961). So, he knew what he was up against, or up for on Judgement Day, should he commit spiritual (and at that time illegal) transgressions.

In many private drawings (never exhibited in his lifetime and rarely thereafter) made before becoming a sculptor, Smithson depicted hunky men in skimpy black leather, flirtatious buxom babes, and intersex individuals. They cavort around a single central patterned rectangle that he likened to an architectural “cartouche” (a decorative panel with flourishes around it) and are interspersed by oozing blobs and lighting bolts, playful signs of sexual energy. These light-hearted scenes of sexual enticement align with Gore Vidal’s later satirical Myra Breckinridge (1968) about machismo, transsexuality, and gender forms then considered deviant, including two anthologies Smithson owned from the magazine of literary erotica, Olympia. But there is no extant evidence in his art of the fantastical accounts he collected in literature of the erotic pleasure that some experience from the infliction or endurance of corporeal pain. It is described in a licentious novel from his collection, The Image (1966), authored by Jean de Berg – the pen name of the French actress, photographer, and writer Catherine Robbe-Grillet (and yes, wife of Alain R-G, himself associated with S&M in art and life) – who narrates sexual sadomasochism among a menage a trois. “I made her come closer so I could run my fingers over the curves and hollows which we were about to wound, with abandon, as long as it seemed entertaining.”

Other instances of “entertaining” a tortured sexuality – physical or emotional– appear in Smithson’s library, including Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writings (1966), and His Life and Works (1948), both by Marquis de Sade who advocated traditionally taboo sexual practices; and the novels of female sadomasochism. The Story of (1967), and Return to the Chateau, Preceded by A Girl in Love (1971) by Pauline Reage and Lady Susan’s Cruel Lover by Joan Ayres (1967).

Characteristically skeptical, in his essay, “A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art” Smithson wrote, “Language ‘covers’ rather than ‘discovers’ its sites and situations.” He was adept at using words to both draw attention to subjects with which he wanted to be associated and to keep them under cover. But he also gave the attentive reader cues, and retained a collection of books important to him, with which to uncover – or perhaps to provide a more intimate and enriching understanding for others of his legacy of visual and verbal expansions.

Suzaan Boettger, an art historian, critic and lecturer, is the author of Inside the Spiral: The Passions of Robert Smithson, described by the Brooklyn Rail as “Definitive. . . an indispensable book for the study, ‘from the inside, ‘of a major American artistic personality.” More details about the book can be found here, and you can learn more about the author on her website.