“So, your mother is a Black feminist? No wonder your writing is so queer!”

I gave a quiet chuckle over the rim of my drink and nodded. I was with a new friend at one of Washington DC’s many chic Black bar restaurants. Stylish couples lined the walls, hair done, shoes on point, radiant in their summer best. All the couples, as far as I could tell, seemed straight. My friend and I, both Black, queer women, guessed that the host, the server, and the smiling manager who came to greet us were all family. Either way, the night was queer to me: “The Glow of Love” by Change featuring Luther Vandross blared across the dining room, and my friend and I bobbed our heads in shared reverence, reading queerness between the lines, delighting in Luther’s voice, this unspoken icon of black, queer life and love, singing:

It’s a pleasure when you treasure all that’s new and true and gay…

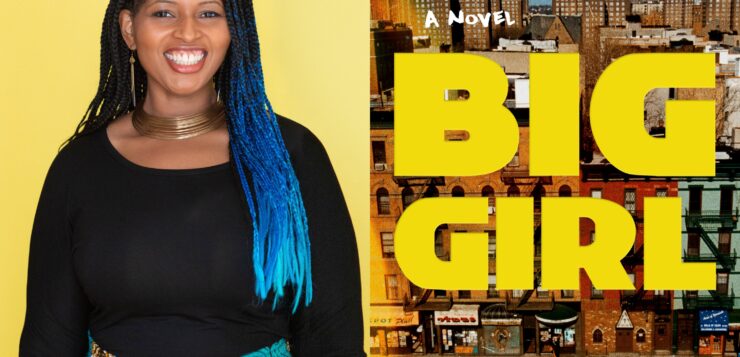

We were celebrating my novel, Big Girl, which had just been shortlisted for an award for LGBTQ fiction. I was excited. All writers like recognition, but this was especially meaningful for me. The novel is about a big, tender-hearted black girl who comes of age in 1990s Harlem, fighting against inherited legacies of body shaming and gender stigmas passed down over three generations of women in her family. The novel means a lot to me, partly because the story is similar to my own, and partly because of how much I learned from the character herself. Malaya, the novel’s protagonist, is inquisitive, quiet, and funny; she has the kind of complex, sometimes contradictory, inner life that I long to see in Black characters. She loves color and food and ‘90s hip-hop. She works hard to love herself. And she’s queer.

As a writer, my characters’ queerness is always as central to their stories as their Blackness, their gender, or their size. For me, this is what it means to create full characters: they have multiple facets, live in multiple worlds, and it’s the precise alchemy of such multiplicity that defines them. As curious as Malaya is about food, she’s equally curious about women’s bodies. Both represent forbidden desires she can’t resist, and stigmas she doesn’t understand.

This matters to me. I was, and am, grateful for every single reader. And yet, when Big Girl came out, I was surprised to find that, in some reviews, queerness appeared as a footnote to a larger story of Black womanhood. These reviews said the novel was about a fat, black girl fighting to make space for herself in the world. It was about gender, race, class mobility, gentrification, hip-hop, and fatness (a topic that is still rarely talked about in literature). But queerness, in some reviews, was often framed as mere experimentation, and sometimes not mentioned at all.

Of course, I shouldn’t have been surprised. As a student and scholar of Black queer feminist thought, I know the traps of intersectionality well. Audre Lorde, Cheryl Clarke, Pat Parker, June Jordan and many others remind us how seductive—and how dangerous—it is to use one aspect of identity (like race or gender) to write queerness out of our life stories. As Lorde puts it, “there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives.” When we fail to acknowledge this, the cost is not just personal, but political. When a story about a fat black queer teenage girl becomes a more general story about body positivity, for example, not only does the character flatten, but the social stakes of the story thin away.

I thought about this as Luther’s chorus rolled full and thick through the low-lit restaurant, my new friend singing along. She had not yet read the novel, and when I told her about it, she asked how the story came to me. I said what I often do: that like my protagonist, I grew up as a fat, Black girl in Harlem, that I was constantly aware of what my body meant to people around me, and how everyone wanted my body to change in ways I could not fully grasp. It was Black feminist literature that helped me through the landscape of my body’s meanings, I told her. I shared how reading Jamaica Kincaid, Toni Morrison, and Ntozake Shange as a fifth-grader helped me understand how Black girls’ bodies are treated as property, as objects, and how such treatment is often the projection of oppressive fantasies of power. I told my friend how these books showed me where black girls’ bodies fit into a historical nexus of race, sex, class, and gender—configurations in which Black women must fight to define and claim our humanity and create our freedom. I told her how, even at that young age, reading these stories helped me feel more powerful and less alone. Finally, I told her I discovered these books not at school, but in my mother’s small Black feminist library in the basement of our home in Harlem.

“So, your mother is a Black feminist?” She sipped her mezcal, the ice clinking against the glass as she raised her eyebrows in a smirk. “No wonder your writing is so queer!”

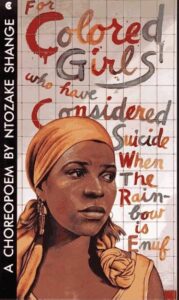

I lifted my own drink, a paloma, and smiled back. I hadn’t thought about it that way, but it was true. While I was poring through my mother’s library, pressing my chubby fingers over the slick first-edition cover of Kincaid’s Annie John, sniffing the powdery paperback pages of Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, and holding up the cover of Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf in the mirror so that the thoughtful, yearning Black girl face on Shange’s cover sat parallel to my own—I was discovering myself in Black feminist literature, and also recognizing myself in the queer parts.

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1975).

In each of these books, race and womanhood are inseparable from delicious intimacies shared between Black girls, and I couldn’t get enough. I read these books ravenously in the quiet of the basement, often whispering the juicy scenes to myself so no one would hear. I studied the moments in Annie John when Kincaid’s young narrator discovers her freedom in illicit games of Black-girl pleasure held during recess at her repressive postcolonial Caribbean school. I admired the ardent, nearly-chivalrous devotion that drives Morrison’s narrator, Claudia, to care for the outcast Pecola Breedlove when their community rejects her for being too dark-skinned in The Bluest Eye. I delighted in the sensual ways Shange’s eponymous “colored girls” moved and healed and touched each other as they told their stories of sex, trauma, and love through for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf. In each of these stories, I discovered that same-sex intimacy, desire, and love are what make freedom possible.

And yet, though many scholars have explored the queer resonances of these and other Black feminist works, none of these stories are widely understood as queer. There are many reasons for this. As writers publishing in the 1970s and 1980s, Morrison, Shange, and Kincaid had little incentive to claim any non-heterosexual identity for their characters, at least from a publishing standpoint. Some black women writers, like Morrison, have explicitly rejected readings of their characters as gay, while others, like Shange, have embraced queer themes and welcomed queer readings of their work. We need these writers’ works regardless. We need their racial histories, their class and gender critiques, and their queerness, explicit or not.

But for me, it’s important to say it clearly: My books are queer. I would no sooner quiet my characters’ queerness than I would their blackness, or their womanhood. I know many contemporary queer writers feel this way. Writers like Marci Blackman, Nicole Dennis-Benn, Ana-Maurine Lara, Janet Mock, M. Shelly Connor, Darnell L. Moore, and many others draw on the legacies of Black feminist literature, naming our characters as LGBTQ+ and make explicit the “new and true and gay” that has lived at the center of our literary traditions forever.

We name our characters’ queerness for ourselves, for our readers, and for the sake of the queer futures we hope our work makes possible— futures in which the many truths of Black, queer life can be spoken, written, and read out loud. I told my friend this, too. Then we laughed and kept singing.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, Ph.D., is the author of the novel Big Girl, a New York Times Editors’ Choice and winner of the 2023 Next Generation Indie Book Award for First Novel, Blue Talk and Love, winner of the Judith Markowitz Award from Lambda Literary, and The Poetics of Difference: Queer Feminist Forms in the African Diaspora, winner of the William Sanders Scarborough Prize from the MLA. She has earned honors from Bread Loaf, the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, the Mellon Foundation, the Center for Fiction, the NEA and others. Originally from Harlem, NY, she is Associate Professor of English at Georgetown University and lives in Washington DC.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, Ph.D., is the author of the novel Big Girl, a New York Times Editors’ Choice and winner of the 2023 Next Generation Indie Book Award for First Novel, Blue Talk and Love, winner of the Judith Markowitz Award from Lambda Literary, and The Poetics of Difference: Queer Feminist Forms in the African Diaspora, winner of the William Sanders Scarborough Prize from the MLA. She has earned honors from Bread Loaf, the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, the Mellon Foundation, the Center for Fiction, the NEA and others. Originally from Harlem, NY, she is Associate Professor of English at Georgetown University and lives in Washington DC.

Discussion1 Comment

Rich, poetic, informative essay. Thank you for writing it.