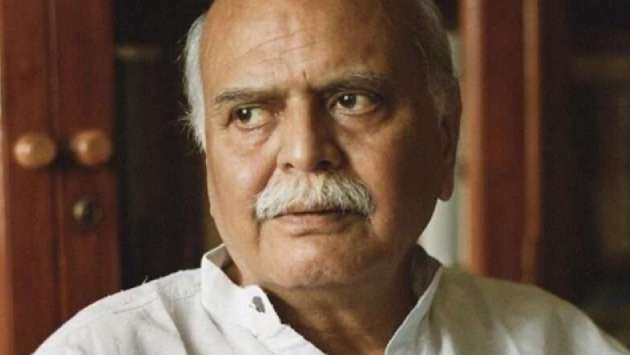

Saleem Kidwai (1951-2021) died in his hometown of Lucknow on August 30, 2021 from a cardiac condition. Death is such a mundane affair and occurs all the time, yet Saleem’s passing came as a shock, feeling both wrong and untimely to me because he had not finished his book on the great Ghazal and Thumri singer Begum Akhtar.

The last time I saw Saleem was at his friend’s house in Delhi in 2009. I moved to Europe soon after and lost touch with him. I always thought I could go back anytime and he would welcome me. There was no particular reason for me to believe so, but he simply evoked these feelings in me. Though weI lost touch, I frequently listened to his occasional talks on YouTube. Saleem’s passionate involvement in the LGBTQ movement in India always compelled me. For many parents of queer children, and for men and women struggling with their sexuality, homosexuality became more acceptable in India because Saleem embodied it.

My interest in the legendary Indian singer Begum Akhtar led me to Saleem. I first met him in a place called Pegs ‘n Pints—an erstwhile gay bar in Delhi, which made for an unusual place for meeting Saleem, a history professor, for a discussion. He was dressed elegantly in a white pajama and kurta, sipping something. I immediately noticed his quiet dignity and presence, a kind of sophistication belonging only to those who spoke perfect English and Urdu, unlike the deracinated young crowd who, no matter how educated, always appeared incompetent in comparison. Saleem spoke as if every stranger had the potential to become a friend. He asked me about Begum Akhtar. Of course, while I knew her music, I could not identify the various genres she sang. He went on to tell me riveting stories about her. Not once did I question whether or not what I was hearing was true. His manner, voice, and choice of words came from a place of deep cultural knowledge, both inherited and cultivated, and the exchange became a kind of cultural transference. Surrounded by loud music and a wealthy Delhi crowd, we managed to make our tiny enclave and talk about Begum Akhtar and her music.

Apart from being a history professor, Saleem was a queer activist, overtly subdued, but emphatically resilient. He eagerly offered his solidarity to a variety of causes, but he did not beat his chest or shout slogans. He was generous with his knowledge and time, always gave helpful advice, and mentored others. He was never concerned that someone would appropriate his ideas; he was satisfied that people were talking and writing about things he held dear. Every significant LGBT organization or support group in India, from the Naz Foundation and Humsafar Trust to Bombay Dost, acknowledged Saleem’s contributions to the LGBT right movement in India. His research, which demonstrated that homosexuality was not a Western import, but a native Indian practice, was submitted as evidence to the Delhi High Court in 2009 to strike down Article 377 which criminalized queer people in India.

Saleem’s greatest contribution lay not in his tangible or spectacular deeds, but in his ability to touch so many lives. In the last twenty years of his life, Saleem emerged as the go-to source for anyone who wrote about Lucknow, Bombay films, tawaifs (courtesans), or Begum Akhtar.

Saleem’s lifelong research interests in Indian history, tawaifs and their lifestyles, and Bombay films are shaped by his sexuality. For instance, he gravitated toward Begum Akhtar because she was a queer figure, in a caste sense. Tawaifs, like hijras and Dalits, were perceived as abject in the dominant Brahminic culture. It was indeed her music that first drew Saleem to Begum Akhtar, but what sustained their relationship over a lifetime was their mutual acceptance and recognition of their queerness. It was this perspective that gave his work on Begum Akhtar a profound quality missing in the works of others.

Almost all of Begum Akhtar’s disciples, elite upper-caste Hindus and anglicized Indians, wrote about her. Like them, Saleem was also anglicized; he studied at St. Stephen’s College in Delhi and later at McGill University in Canada. However, he was also deeply familiar with his own elite Muslim cultural ethos in which tawaif arts and feudal culture converge, giving his writing a unique perspective on sociopolitical issues. Rita Ganguly, a student of Begum Akhtar, wrote in her book that children of “gharana” families, or those who collectively learned a distinct style of music, instinctively know etiquettes of music that eluded learners from non-gharana families, even after years of training.

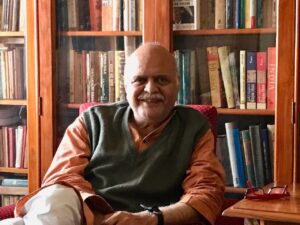

As a scholar, Saleem never distanced himself from his cultural heritage, unlike many of his contemporaries who fully embraced the English language and Western culture. Of course, Saleem made detours before taking his destiny into his own hands. Like many other gay men of his generation, Saleem moved to the West for greater freedom. But he returned to India soon after realizing that as a scion of an elite Muslim family, he could do much more for gay liberation in his own country than he could in Canada, where during a police raid in a Montreal gay bar, he was turned into a criminal overnight.

Since 2014, India has increasingly developed into a chauvinist, Muslim-hating Hindu state. It is apparent from Saleem’s work that, while he did not ignore anti-Muslim politics, he remained refreshingly removed from petty biases and prejudices. Many of his close friends were, and remained, Hindus. As a queer person, he learned early on how important openness toward others was for queer survival. In popular discourse, Saleem’s close friend, the poet Agha Shahid Ali, and his favorite singer, Begum Akhtar, are frequently described in Sufi, or mystic, terms. The works of author Amitav Ghosh and singer Rita Ganguly offer good examples of this. After Saleem died, the way people remembered him emphasized his generosity in a similar way. Saleem, Begum Akhtar, and Agha Shahid Ali were close friends, the underlying connection between their works and sensibilities became apparent only after they were gone.

Although soft-spoken and affable, Saleem never hesitated to give his opinion when necessary. On one occasion, talking about a specific couple from different class backgrounds, he pronounced such an arrangement would not last. I instinctively rejected his argument (this couple is still together). But the more I saw of the world, I came to understand that Saleem was not wrong, but simply had no blinkers on. On another occasion, he described an elderly singer friend of mine, whom he also knew, as a “behuda” (frivolous) woman. I resented this, not realizing that while my friendship with the singer was only two-years-old, he grew up with her. Recently, when I published an essay about Begum Akhtar, the same singer accused me of stealing her ideas, but when I questioned her as to how, she didn’t reply. I thought of Saleem and let her behuda remark pass.

Knowing my interest in Begum Akhtar, Saleem frequently invited me to visit his house in Lucknow where he curated a significant amount of material about her, adding with a smile that he had Begum Akhtar’s telephone diary, in which the first entry is of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (although a die-hard Begum Akhtar fan, Saleem was not a stranger to her flaws).

Unless one has the right introduction or connection, the Indian academic or middle-class world is not open. Therefore, whenever Saleem asked me to visit him in Lucknow, I thought he was hitting on me. Given the way people recalled him, I evidently misinterpreted his generosity because of my limited experience in Indian academia. In retrospect, to be admired by Saleem romantically (if that were true) now feels like a compliment.

Following his death, those who knew Saleem spoke about him in a live online event with honest affection, in ways that matched the Saleem I knew. Although I enjoyed listening to what they said about him, I also realized the best way to remember him and “to spend time in his company” was to read his work. It energizes me and brings him alive. Once, he said to me that Begum Akhtar had a terrific sense of sam (the main beat in north Indian music); Saleem’s essays also have that quality. They end at a point when they should. Even though Saleem didn’t write much, and never finished his much-awaited Begum Akhtar book, he made a significant contribution to Urdu literature and the Indian queer movement. His essays on tawaifs, his translations of Qurratulain Hyder’s novels and courtesan Malika Pukhraj’s autobiography into English, and his book Same-Sex Love in India co-authored with Ruth Vanita would keep him alive.

Lucky Issar is an independent researcher and literary scholar. He holds a Ph.D. from Freie Universität Berlin. His research interests include gender and queer studies and queer theory that focuses on India. His forthcoming work is scheduled to be published by the University of Tennessee this year. He has contributed scholarly articles, essays, and book reviews to various publications including Himal, Economic and Political Weekly, Modern Fiction Studies, Victorian Review, and the journal, Literature and Theology.