I ENLISTED in the U.S. Air Force a year after North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950. I wanted to be a pilot, something that seemed glamorous to my nineteen-year-old eyes—which, unfortunately, I failed to have examined before signing on Uncles Sam’s dotted line. The military doctors discovered that I had 20/40 vision in my left eye, which immediately disqualified me from pilot training. The next best option was to become an academic instructor. At the time, the requirement was two years of college, which I had, so I entered instructor school just under the wire before the bar was raised to college graduate. It was an early lesson that timing is a very important element in life.

I remember clearly the psychological test of my suitability as a heterosexual man. An officer asked me if I “liked girls.” I answered “Yes” —and I wasn’t lying. At the time, I didn’t realize I was gay. I hadn’t yet had a sexual experience with another man. Eisenhower—“Ike”—was president, and he thought America’s young men should know their country’s history, so a small number of instructors were chosen from training bases around the country to attend a special school at Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas. They were supposed to be poster boys for what a young American male should be. I was among those chosen and soon found myself with my fellow airmen in San Antonio.

I remember clearly the psychological test of my suitability as a heterosexual man. An officer asked me if I “liked girls.” I answered “Yes” —and I wasn’t lying. At the time, I didn’t realize I was gay. I hadn’t yet had a sexual experience with another man. Eisenhower—“Ike”—was president, and he thought America’s young men should know their country’s history, so a small number of instructors were chosen from training bases around the country to attend a special school at Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas. They were supposed to be poster boys for what a young American male should be. I was among those chosen and soon found myself with my fellow airmen in San Antonio.

One weekend, a group of us decided to go to a well-known house of ill repute across the Mexican border in Nuevo Laredo. After having a few beers and sowing our wild oats with the available women, we crossed back to the American side and checked into a motel in Laredo. I shared a room with a guy named Rick from Parks AFB outside San Francisco. We undressed, looked at each other, and walked into each other’s arms. Not a word was spoken. We were both amateurs and probably just did the “Princeton rub.” So, I lost my virginity twice in one night, first with a girl and later with a guy. In retrospect, the curious thing about my encounter with Rick was that after that night the incident was never referred to again, and we continued to double date with girls until graduation two months later. Indeed, from that evening on, Rick and I were inseparable as “buddies.” Rick returned to his base in California and I went back to New York. We lost contact, but I have pictures of the two of us on the beach on Padre Island, off Corpus Christi. I never looked happier.

The infamous McCarthy hearings formed the backdrop for my early days as an instructor. The hearings were as much about rooting homosexuals out of government as they were about outing Communists in Hollywood, with the deeply closeted attorney Roy Cohn guiding the inquisition as McCarthy’s chief counsel. Between classes, most of the instructors would go to the dayroom to watch the riveting events unfold on TV. The lesson we took away was that being gay while in government service was the worst thing that you could be. It’s no wonder many gay men got married in the 1950s, as it was the closest thing to a perfect cover.

The first gay military man I knew was Paul. He introduced me to my first gay bar, the Old Colony on 8th Street in Greenwich Village. Of course we wore civvies every time we ventured off base. Being discovered as gay usually meant a dishonorable discharge, a stigma that would follow you for the rest of your working life. Unfortunately, Paul was outed by a guy in Korea who implicated about ten men he said he had sex with stateside. I testified at Paul’s court martial and answered absurd questions under oath, such as: “Did you notice him looking at you while you undressed?” Although not discharged, Paul was demoted and stripped of his elite status as an instructor, forcing him to languish in the motor pool for the rest of his enlistment.

New York City was about three hours away by car. I didn’t own one, but Paul did, a 1948 Nash, which was built like a tank. The first time we went to the Old Colony I was amazed by the number of men in the place. At the end of the bar stood one of the most handsome men I had ever seen on or off the silver screen. This vision approached us and asked my name. Thus began my first gay love affair.

His name was Victor and he had a penthouse apartment on 10th Street. He was a 31-year-old television director—an older man! In those days, dramatic TV shows were produced live. Programs like Playhouse 90, Studio One, and Kraft Theater gave many fledgling actors and writers their first break in the new medium of national television. Victor was not only talented but a well-known figure in television circles. He was also a caring, loving man, and I realize now how fortunate I was to have been introduced to the gay world of New York by him.

In those days, Broadway shows and fashionable supper clubs were places where straights and gays mingled freely. I remember vividly an evening at the Byline Room, where the great chanteuse Mabel Mercer held forth, sitting between Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner on one side, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor on the other. When I visited Victor in New York, the fear of discovery vanished. I felt accepted by the arts community. When Victor took me to see the musical The Boy Friend, starring the unknown English actress Julie Andrews, we went backstage to chat with her briefly after the performance. He seemed to know everyone. Heady stuff for a shy twenty-year-old interloper in civvies!

Back at the base, the lieutenant in charge of the academic squadron asked me to be chief clerk in his office. This was comparable to Burt Lancaster’s job in From Here to Eternity, a male secretary to cover for him while he was out playing golf. I supervised an office of four other airmen and fielded questions and calls for the mostly absent lieutenant. I enjoyed the prestige and power that this position afforded. I also kept a picture of Victor, taken when he was a World War II pilot, hidden at the bottom of the footlocker in my barracks room. I shudder to think what would have happened if there had been an unscheduled inspection. But the instructor barracks on a training base was more like a frat house than traditional quarters. We were an elite group and mostly left alone.

My roommate was a wonderful guy named Stewart McKinney. I was best man at his wedding. If the name sounds vaguely familiar, Stew was a U.S. congressman from Connecticut who died of AIDS in 1988. By then, we had lost touch and were leading different lives. He was married with four children and had a secret male lover in Maine. He called me unexpectedly from Washington early in 1988 and paid a brief visit, traveling under an assumed name. He looked thin at the time, and only after his death did I realize that he had come to say goodbye, although that word was never spoken. In the two years that we shared the same room together, there was never a moment when he displayed any sexual interest. Ironically, it was only once, at his bachelor party the night before his wedding, that he confessed his desire for me. What we shared during those years in the military would be called a bromance today.

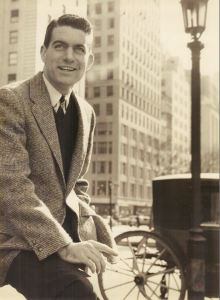

Many military men were dishonorably discharged for being gay in the early ’50s. You suppressed your gay emotions or, like me, found an outlet outside the military structure. Shortly after my honorable discharge from the Air Force in July, 1955, I discovered the famous “bird circuit” of gay bars run by the Mafia, headed by the legendary Blue Parrot. The mobsters paid off the police for our protection. I was also “discovered” on a street in Manhattan and became a model (a life I described in the March-April 2016 issue of this magazine).

Suppressing your true self was necessary for survival, but left the inevitable scars of self hatred that have taken me most of a lifetime to overcome. Remember The Boys In The Band? I was one of those guys, but I was fortunate enough to survive into a more liberated age.

Peter Jarman is a retired advertising agency executive living happily in San Diego. He can be contacted at pjarman@san.rr.com.