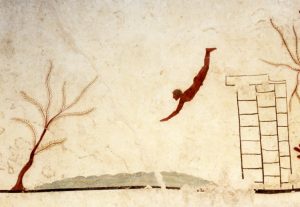

I AM AFRAID of deep water and I am afraid of dying. I am not alone in these fears. And, yet, an ancient frescoed image discovered at Paestum, of a slim youth diving into the waters of the afterworld, exhilarates me and lessens those worries. Art has such power.

When I first saw that image this past summer on a fragment of limestone in the museum at Paestum in southern Italy, I felt an infusion of joy that comes only upon seeing a certain work of art that affects us for reasons we can’t fully articulate. I bought a cup in the gift shop that features the image and on my first morning back home, after nearly three weeks away, I drank my coffee from it and will likely do so every morning from now on. I don’t think I’ll ever tire of this image because it shows a beautiful figure in a pose of grace.

After seeing this circa-470 BCE fresco that had once filled the inner covering of a tomb, I crossed the road and entered the ruins on a blazing July day. With no barriers in place, I was able to climb amid the remnants, as if the site was my own discovery—no velvet ropes or fences or wall-mounted cameras to impede my progress. I walked to the perimeters of the excavated site, a colony/city where thousands once lived. To do so, you have to pass through the ruins of Greek and, later, Roman houses that were built for families beginning in the 7th century BCE.

You occupy the rooms—absent their ceilings and full height of the walls—where men and women, boys and girls lived and slept and cooked and conversed. People made love in these rooms, fought, ate, lounged, worried, laughed. Long, straight paved roads connect their homes, intersecting in a perfect grid with other streets. A community pool—not the waters the frescoed boy is about to pierce—lies near one end of the city, or at least what has thus far been excavated of it. Elsewhere is an amphitheater, and across the landscape march three Doric temples, which have come to identify the site, earning it a UNESCO World Heritage designation.

I went as far into the complex of ruins as I could amid the chorus of cicadas and came to bountiful fields of a green crop, perhaps rye. Beneath those fields there are probably more houses and public buildings from the city that flourished here between 600 BCE and 450 CE (it was a local farmer who had first found these frescoes in the 1960s). That’s over a thousand years, a long run for any city.

I love that the ancient Greeks and Romans unabashedly depicted, versed about, sculpted, frescoed, and mosaicked handsome men and their attractions to one another. The museum at Paestum includes the other slabs found in what is now referred to as the Tomb of the Diver, all of which depict men at a symposium, a banquet, in affectionate embraces and glances. They are clearly enjoying each other’s company. Whoever painted the scenes did so lovingly to reveal this dynamic. There are many ways I could interpret this fresco’s images, which now haunt me, though in a good way. If in death, beautiful slim young men come to join you, well, that would be a good thing. And if a new world of life exists beneath the warm waters of the Underworld, then that, too, is a hopeful notion.

One of the perplexing dynamics of the ancient Western world for me, particularly of Greece and Italy, is how far ahead they were of everyone else in the world—and may still be even now. Did they really possess a knowledge of an afterlife, a world of gods and spirits that we do not? Did they know certain truths about such mysteries? Why paint an image on the interior cover of a tomb that no one will see—unless the deceased occupant has the ability, somehow, to keep seeing it? Because the diving male youth was painted on the cover of the tomb, that is what the occupant would be seeing for eternity.

I think, too, of how the Romans invented the arch, itself a wonder of architecture and physics. And once they figured out how to erect arches, they did so everywhere, exploiting them in handsome rhythmic patterns visible at Paestum and at countless Roman sites and villas. They and the Greeks understood, too, how to sculpt their Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns—not only for structural reasons, but also for æsthetic effect. Temples erected to honor female goddesses at Paestum, for instance, use columns that taper in what’s known in architecture as entasis, referencing a woman’s body.

What imagination it took to show a diving slim youth as a symbol of death and of life thereafter. So much of what those ancient people built and lived with endures. The copper-hued figure with a small, trimmed chin beard, appears to be smiling in the midst of his dive, his eyes open. Like a swim-team diver, his body arcs perfectly, his even ribcage running along a flank. The platform from which he has jumped suggests a series of Doric columns with their rigorously geometric capitals. The water is a warm light green, and the way its waves billow in the scene makes it appear soft as a cloud, as if diving into it causes no pain, just a cleansing. Even the dancing branches of the tree flourishing on the far shore seem to beckon him in his dive. Millennia ago, an artist painted a scene that provides solace to this day.

David Masello, a writer about art and culture, is based in New York City.

David Masello, a writer about art and culture, is based in New York City.