THE ANNALS of gay history are littered with examples of men in the public eye who have successfully hidden their gay lives from view. They’ve used various strategies, such as marriage to a woman, to camouflage their sexual activities and to discourage gossip. Eugen Sandow was, for a short time, an exception to the rule. He was internationally known as the apotheosis of male beauty and the most perfectly formed man on the planet. Little remembered today, Sandow was the father of modern bodybuilding—and, for a short time at least, he was open about his sexuality: when he began his rise to international stardom in Chicago’s Loop in 1893, he arrived with his boyfriend in tow.

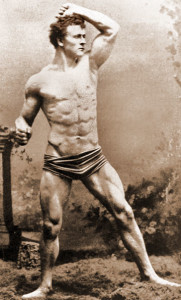

Just a few years earlier, in 1885, Sandow left his home in Prussia at age eighteen to avoid the military draft, touring the Continent with circuses, taking part in wrestling matches, and giving exhibits of strength to make a living. In early 1887, he found himself stranded and jobless in Brussels. To make ends meet, he modeled nude for established and up-and-coming artists, some of whom paid for more than his ability to stand still (Fig. 1). Befriended by Professor Attila (Louis Durlacher), a famous local strongman and founder of his own bodybuilding school, San-dow became Attila’s star pupil, and for the next year, he diligently chiseled his body into a piece of art, one rivaling the classical statues that he admired.

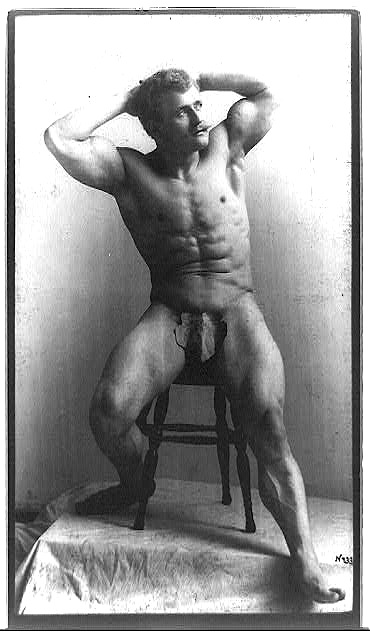

Sandow left Brussels for Venice in 1888 and paid a visit to the Lido, a well-known cruising area for gay men. Much later he would claim (in an article in Strand magazine, March 1910) that he’d been swimming in the ocean when he noticed that “I had become the particular attraction for a gentleman sauntering by. As I apologized in passing him he stopped to compliment me upon what he was pleased to term my ‘perfect physique and beauty of form.’ That casual critic proved to be none other than Aubrey Hunt, the famous [English] artist, with whom I afterwards became on terms of close friendship, and to whom I had the pleasure of posing in the character of a Roman gladiator.”

Gay men easily read between the lines: Hunt was cruising the beach; Sandow was drumming up trade and knew he’d caught Hunt’s eye. By speaking first, he indicated that he was available, allowing Hunt to respond according to his wishes. By complimenting the Adonis quality of his body, the gentleman declared his desire for the 22-year-old hunk. Hunt’s painting of Sandow, The Gladiator (Fig. 2), depicts the model in gladiatorial drag, standing in the middle of what appears to be a Roman arena, with crowds and other background elements out of focus. What is in focus is Sandow’s highly-chiseled body, which is clearly seen as an object to be ogled and adored. The Gladiator is soft-core porn, late 19th-century style, and it gave Sandow an idea.

For the next six years, Sandow merchandised his body by posing for photographs, garnering profit and publicity for himself. He is often almost fully nude, his genitals hidden only by a well-positioned fig leaf. The photos were distributed as studies to inspire men who were involved in “physical culture,” the contemporary term for bodybuilding. But Sandow’s poses were also highly erotic spectacles targeted to gay men. The shape of the fig leaf, how the photographer (or Sandow) positioned it, how the photographer arranged the studio light to strike it, and even its size were calculated to tickle gay men’s fantasies. Light on the fig leaf was used to suggest penis length and girth (Fig. 3), and the fig leaf might even be positioned to suggest an erection (Fig. 4).

Sandow’s erotic appeal wasn’t just his good looks and muscles, nor the titillating fig leaf. Some poses included subtexts that seem to be there for the benefit of certain men. In “The Dying Parthian” (Fig. 5), for example, some viewers might see only a valiant but vanquished warrior defending himself with his last breath. Nude, on the ground, weakened by battle, he heroically continues. But he’s also raising his sword to produce an effect that, because it extends from his crotch, is undeniably phallic. He seems to be offering it to the soldier who’s just defeated him in battle (a peace offering? a bargaining tool?).

In “The Dying Gaul” (Fig. 6), the nude Sandow, again lying on the ground, looks up. His thighs are spread, his right arm up, his right hand open, palm out, imploring the gods to spare him from impending death even as his face suggests a pained acceptance of his fate. This, at any rate, would be the “straight” interpretation of the scene. However, a gay man might be forgiven for seeing Sandow in a state of sexual arousal, perhaps reaching toward his lover, his thighs spread in invitation. Indeed his expression is that of a man in an erotic swoon, not in the last throes of life.

As Sandow was posing for Hunt in Venice, Edmund Gosse, a well-known English writer, was buying Sandow’s photographs in a London shop. He called them “a beautiful set of poses showing the young strongman clad only in a fig leaf” (Chapman, 1994). Gosse was so enthralled with the photos that he sneaked them into the funeral of poet Robert Browning at Westminster Abbey to peek at during the service. He later sent copies of them to another writer, John Addington Symonds. In acknowledging the gift, Symonds was circumspect, though his prurient exuberance comes through loud and clear: “The Sandow photographs arrived. They are very interesting, & the full length studies quite confirm my anticipations” (Symonds, 1969). Gosse and Symonds were part of a group of men that also included Oscar Wilde’s lover, Alfred Douglas, who exchanged photos of young men in the nude.

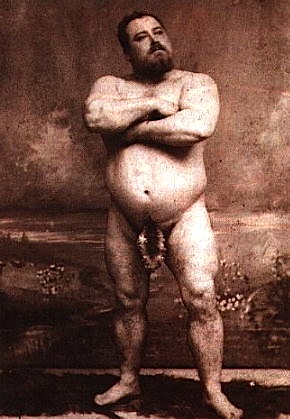

Sandow wasn’t the only physical culturalist to be photographed during the 1880’s and 90’s, but he was unique among those who were. Others developed their bodies into machines for lifting incredible weights but did little more. Sandow’s performances included weight-lifting extravaganzas, as did theirs, but he also assumed formal poses to exhibit his sculpted body in a sexually suggestive way. Audiences might be in awe of the hundreds of pounds that Luis Cyr could lift, but the barrel-shaped Cyr’s sex appeal was nil (Fig. 7). In contrast, when the buff Sandow donned his form-fitting leotard and singlet for live performances, audiences cared “little how much he could lift, or whether he could lift anything at all,” in the words of an article called “How the World Went Mad over Sandow’s Muscles” in Literary Digest (Oct. 31, 1925), because they “attended his exhibitions to look and be exalted by pure beauty.”

By April 1893, Sandow was famous throughout the U.K. and Europe, having won countless weight-lifting contests and drawing thousands to his performances. Word of his feats reached across the Atlantic to the firm of Abbey, Schoeffel & Grau, vaudeville impresarios, who contacted Sandow in London and invited him to perform in New York. Sandow eagerly signed on.

But his U.S. debut flopped. A stock market crash that spring had created an economic depression that thinned out audiences, and a heat wave was engulfing New York, keeping people out of crowded buildings. Then, when things looked their bleakest, he was hired by a theater called the Casino to appear in the smash hit Adonis, starring heartthrob Henry E. Dixey. Beginning on June 12, 1893, Sandow appeared as an epilogue to the play, never speaking a line but lifting weights and posing up a storm (Fig. 8). The plot of Adonis parodied the Pygmalion and Galatea myth (see Kasson, 2001):

A sculptress has created in her statue of Adonis a “perfect figure.” Indeed, he is so beautiful and alluring that she cannot bear to sell him as promised to a wealthy duchess. Seeing Adonis, the duchess, together with her four daughters, is instantly and passionately smitten as well. The daughters try to conceal their ardor [but fail]. To resolve the question of ownership, an obliging goddess brings the statue to life. … The pursuit of Adonis [by the women]rapidly [ensues]. …. Ultimately, Adonis is cornered by all his female pursuers, who demand that he choose among them. Instead, he beseeches the goddess who gave him life, “Oh take me away and petrify me—place me on my old familiar pedestal—and hang a placard round my neck:—hands off.” Thus, exhausted by his stint as a flesh-and-blood object of desire, Dixey as Adonis reassumed the pose of a perfect work of art as the curtain fell.

Adonis’ rejection of female lust must have thrilled the gay men in the audience. When the curtain fell on the night of Sandow’s debut, the audience applauded and waited for the curtain to rise and for Dixey and other cast members to return for ovations. But when the curtain rose, Sandow was standing in the same pose that Dixey had been in when, as Adonis, he was turned back to stone. The audience gasped and then went wild. Sandow was an immediate sensation.

While appearing at the Casino, Sandow was living openly with another man, the composer and musician Martinus Sieveking. The two men met when both were nineteen and formed a bond the nature of which seems obvious enough but which somehow didn’t compromise either man’s career. A reporter for New York World (June 20, 1893) described their arrangement thus:

Sandow is living now at No. 210 West Thirty-eighth Street. With him there lives a friend, Mr. Martinus Sieveking, who is a very able pianist. Mr. Sieveking is a Dutchman. His musical compositions have already attracted considerable attention in London, and he is an unusually brilliant artist. He and Sandow are bosom friends. He thinks that Sandow is a truly original Hercules, and that no one has ever lived to be compared to him. Sandow thinks that Mr. Sieveking is the greatest pianist in the world and that he is going to be greater. It is pleasant to see them together. Mr. Sieveking, who is a very earnest musician, practices from seven to eight hours a day on a big three-legged piano. He is decidedly in earnest. He practices in very hot weather, stripped to the waist. While he plays Sandow sits beside him on a chair listening to the music and working his muscles. He is fond of the music and Sieveking likes to see Sandow’s muscles work. Both enjoy themselves and neither loses any time.

Gay men no doubt loved learning that Sieveking rehearsed half-naked while Sandow worked out, and that “neither loses any time,” whatever that might mean.

Their relationship was an open secret among London’s cognoscenti, which didn’t stop one woman from trying to pry the couple apart. Caroline Otéro, called “La Belle Otéro,” was an infamous Spanish courtesan and lover of King Leopold of Belgium, Prince Albert of Monaco, the future Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, and Prince (later King) Edward of England, among others. Inviting Sandow over to her place for dinner, she apparently spent hours trying to seduce him, but he fended off her every move. She finally accepted defeat and sent him on his way.

When Sandow moved to New York, Sieveking came along, but the latter wasn’t just the muscleman’s boy toy. Sieveking wrote some of the music for Sandow’s performances, notably “March of the Athletes” and “Sandowia,” and also played them on the piano as the Adonis strutted across the stage, giving the act a touch of class. But more than that, Sieveking was a concert pianist and composer with an important career in his own right.

It was in July 1893, when Adonis was about to close in New York, that Sandow was lured 700 miles west to appear in America’s Second City during the Chicago World’s Fair. The father of Chicago-born Flo Ziegfeld, who would later become one of Broadway’s most successful impresarios with his “Ziegfeld Follies,” had bought the Trocadero Theater in the Loop and planned to make huge profits by drawing fair-goers to performances. The Trocadero’s board of directors sent Flo Ziegfeld to New York to hire Sandow, who debuted at the Trocadero as the season’s headliner on August 1.

To deflect gossip about Sandow’s relationship with Sieveking, Ziegfeld, now Sandow’s manager, created a number of rumors to underscore Sandow’s he-man image by linking him romantically to several women, notably the alluring beauty Lillian Russell. He also beefed up Sandow’s act and, in a move that would catapult Sandow into international superstardom, he changed Sandow’s costume. Before Chicago, Sandow had performed in a neck-to-toe pink leotard and blue singlet, but Ziegfeld stripped him down to a pair of skin-tight, white silk trunks. Newspaper illustrations of the time almost always show Sandow from behind, suggesting that a frontal view would have been too scandalous to publish. In the few frontal views that were published, his boxers are usually darkened to conceal the offending bulges.

Sandow’s debut in his skimpy outfit received thunderous applause, and as Sandow took his bows, Ziegfeld appeared on stage, announcing that women who donated $300 to charity could come to Sandow’s dressing room to caress his muscles. Mrs. Potter Palmer and Mrs. George Pullman, grand dames of Chicago society, were first in line. However, men got in for free, and they were the ones who crowded Sandow’s room. It wasn’t the first of Sandow’s after-hours performances. In Europe, he had given private soirées after his act, but they had been confidential and sporadic. Ziegfeld made them public and regular, guaranteeing that they would be a topic of gossip for Chicagoans for months to come. It was so successful that Sandow held them during his entire run at the Trocadero.

When this run ended, Sandow and Sieveking hurried back to New York and from there sailed to England. Sandow visited Warwick Brooks, who had photographed him four years earlier. He also met Brooks’ daughter Blanche, with whom he began corresponding. Sandow and Sieveking then returned to New York to begin their first coast-to-coast tour, which lasted twice as long as the contract required. Their first tour had begun in December and closed the following July. Sandow triumphantly conquered the hearts—and libidos—of audiences wherever he performed, whether on-stage or in private. He sailed back to London and, on August 8, 1894, shortly after his twenty-seventh birthday, he married Blanche Brooks.

Whatever else it might have done for him, Sandow’s engagement—which had been announced the previous January—had camouflaged his domestic arrangement with Sieveking. With a fiancée, he could have his cupcake and eat him, too. Nevertheless, by July the two men had called it quits, and the newly married Sandows began planning a second Ziegfeld tour in the U.S.—without Sieveking.

Sandow changed his performance drastically, too, and Ziegfeld wasn’t happy about it. With wife in tow, Sandow axed the private, flesh-caressing soirées. The second tour became a lackluster series of performances lasting almost eight grueling months. By its end, Ziegfeld and Sandow were barley speaking, and Blanche, who left the tour early, was pregnant with the first of their two daughters.

Following Sandow’s lead, Sieveking also married, in 1899, fathering a son. He moved to the U.S. and gave concerts with good-to-lukewarm reviews at Carnegie Hall and other venues. He also opened a piano school and wrote and published scholarly essays about piano playing. He and his wife eventually separated. He moved to Pasadena, where he died in 1950 at 81.

Sandow and Blanche stayed together, raising their two daughters. Sandow toured many countries throughout the world, created an empire of bodybuilding journals and schools, invented several physique-training devices, and endorsed dozens of products, all of which made him wealthy and a household name. He died at age 58 in 1925. Authorities officially—and ironically—attributed his death to a strain he received when, after his car flipped over during an accident, he righted it.

Sandow’s body, which had given him fame and fortune, which had been caressed by hundreds of trembling hands, and which had been photographed in every pose imaginable, was buried without a tombstone—and then ignored. In fact, Blanche vehemently denied fans the opportunity to raise a headstone to their hero. She was retaliating. Blanche had heard the rumors about his liaisons with men long after Sieveking and he broke up. She also knew, as reported in The Advocate (March 14, 1973), that certain “Cabaret acts and stage revues often featured performers who imitated Sandow with satirical intent. One skit in the musical pastiche L’Amour is especially revealing. An actor representing what is obviously Sandow impersonating a statue, is standing on a pedestal in a park. A bevy of young beauties cross in front. No reaction. Finally a sailor passes, and the fig leaf begins to rise and rise, until it stands straight out supported, obviously, by an erection.” This and other skits showed Blanche that everyone in Europe knew her marriage was a sham. To get back at Sandow for making her an international laughing stock, she kept his grave unmarked to prevent fans from making it a shrine.

An internationally admired figure during his life, Eugen Sandow is little known today. Even those bodybuilders who owe much to his vision and savvy, to his eagerness to merchandise his body in any way that was profitable, and to his exhibitionistic impulses, are unaware that the trophy that is given to the winner of the Mr. Olympia competition, bodybuilding’s most prestigious award, was designed from one of Sandow’s photographs, right down to the fig leaf.

References

Callen, Anthea. “Doubles and Desire: Anatomies of Masculinity in the Later Nineteenth Century.” Art History 26, Nov. 2003.

Chapman, David L. Sandow the Magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the Beginnings of Bodybuilding. Univ. of Illinois Press, 1994.

Kasson, John F. Houdini. Tarzan, and the Perfect Man: The White Male Body and the Challenge of Modernity in America. Hill and Wang, 2001.

Sandow, Eugen. “My Reminiscences.” Strand Magazine 39, March 1910.

Symonds, John Addington. The Letters of John Addington Symonds: Volume 3, 1885-1893.

Jim Elledge, PhD, is professor of English at Kennesaw State University in Kennasaw, Georgia.

Discussion1 Comment

Pingback: 20170126