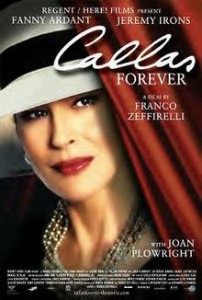

Callas Forever

Callas Forever

Directed by Franco Zeffirelli

Scenario by Martin Sherman

FRANCO ZEFFIRELLI, the director who brought TV audiences the miniseries Jesus of Nazareth and movie audiences Mel Gibson as the Sweet Prince in Hamlet and last year’s Tea with Mussolini, has rocketed to new depths with this butchering of singer Maria Callas in Callas Forever.

Based on his relationship with Callas, played by Fanny Ardant, Zeffirelli’s “fantasy”—his word—is set in 1977, the last year of Callas’s life. Larry Kelly, played by Jeremy Irons, was once Callas’s manager but now manages a rock band called Bad Dreams. His current job is a daunting task, but, despite its drug-related shenanigans, the band is low-maintenance compared to Callas with her diva’s tantrums, which Kelly had tolerated way back when.

In France for a Bad Dreams concert, Kelly has an idea of how to bring Callas out of her miserable retirement. Once considered the eighth wonder of the world, the singer’s voice is now in decline. And while she can still produce sounds that would make Mariah Carey or Celine Dion’s highest notes sound like a howl, the consummate perfectionist refuses to perform.

Add to that her broken heart over Aristotle Onassis’s marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy, and then his death in 1975, and you get a Callas who for all apparent intents and purposes is done with performing. (Her last live performance was back in 1965.) Ho wever, Kelly’s visit to Callas has a purpose: he intends to get Callas to perform again. Well, sort of. Thanks to the recent advent of lip-synching, Kelly proposes to Callas that she perform her operas for the silver screen. She will act, but the singing will be from one of her old recordings and she will lip-synch the words.

wever, Kelly’s visit to Callas has a purpose: he intends to get Callas to perform again. Well, sort of. Thanks to the recent advent of lip-synching, Kelly proposes to Callas that she perform her operas for the silver screen. She will act, but the singing will be from one of her old recordings and she will lip-synch the words.

Unlike Ashlee Simpson or other so-called divas of today, Callas finds lip-synching dishonest, and on hearing the suggestion throws Kelly out of her beautiful Paris home looking out at the Eiffel Tower. Meanwhile, her depression over her failing voice and her lost love deepens further, to the point that Kelly, with the help of a journalist named Sarah Keller (Joan Plowright), decides to intervene. That Callas will eventually be persuaded to come out of retirement seems inevitable from the start, or there would be no movie. The choice for their first film is Bizet’s Carmen, an opera that Callas had only recorded but never performed live. So the production commences and Callas performs well, throwing a few tantrums into the mix, and the film gets made.

A second project is proposed, but negotiations stall, and Callas decides that she actually wants to sing in any forthcoming films. Financial backers are incredulous. Amid the turmoil, Callas abruptly announces that she wants Kelly to destroy the print of Carmen before it’s released in order to protect her legacy. Despite the fortune it will cost him, Kelly agrees.

Now I have no doubt but that Callas would have felt this way about lip-synching, even if it was her voice and not some machine’s, but this scenario is Zeffirelli’s fantasy and adds nothing to our understanding of its subject. Maria Callas was the greatest soprano of the 20th century, and she knew some of the most important people in the world. She was born in New York to Greek parents and went on to star on the world’s greatest stages. She broke off relations with her mother in 1950 and the two never reconciled. She left her husband and started a nine-year fling with Onassis—who’s rumored not to have treated her very well. She ruined her voice for a very important concert before Italy’s president Giovanni Gronchi because she partied the night before. If Zeffirelli and co-screenwriter Martin Sherman couldn’t find any material to work with in these real events, they should have left the story to greater minds.

Making matters worse, Zeffirelli concentrates on a subplot involving Larry’s romance with Michael, a painter who idolizes Callas. If the movie has a saving grace it is the acting of Fanny Ardant, whose odd job it is to lip-synch the real Maria Callas while enacting the part of Callas lip-synching herself, something she never actually did. Perhaps the director is trying to create an urban legend—is it possible that he, Zeffirelli himself, actually did make such a movie and then, at Callas’s insistence, destroyed the only print?—but he has not added much to the singer’s already outsized legend.

John Esther is a cultural writer based in Los Angeles.