THE DAY AFTER the first night of rioting at the Stonewall Inn in late June, 1969, the police barricades were taken away from the city streets. But the intensity of the previous night’s disturbance—where about 500 had gathered in protest outside the Inn, some shoving or throwing bottles, others lighting small fires—was still palpable. Ellen Shumsky walked through the streets of her neighborhood where trash cans that had been set ablaze emitted still-smoldering ashes. The aftershock of rebellion, rage, and frustration that burst forth onto Sheridan Square was recognizable to her.

Shumsky had photographed the student rebellion in Paris at the Sorbonne the year before in 1968, when major riots took place with police throwing grenades from behind makeshift barriers, beating, then arresting, student protestors who returned fire with makeshift Molotov cocktails. The French student rebellion became a worldwide phenomenon, and protests erupted from Paris to Mexico City and from Berlin to Cairo—then in 1969, it was the incendiary year in Greenwich Village, the epicenter for the birth of the modern gay liberation movement.

During the late 1960’s, Shumsky was living in the Languedoc region of Southern France, having bought a small farmhouse for $1,300. She was studying photography with mentor and brother-in-law Harold Chapman, who photographed the Beat Generation writers Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac at a rooming house that became known as “the Beat Hotel” at 9 rue Git-Le-Coeur on Paris’s Left Bank. Chapman had told her: “A picture you take today is history tomorrow.” She became a documentarian, shooting photographic portraits of people without warning, unposed and unrehearsed. Her recently published book, Portrait of a Decade: 1968 to 1978 (Graeae Press), includes documentary images taken with her Pentax 35mm.

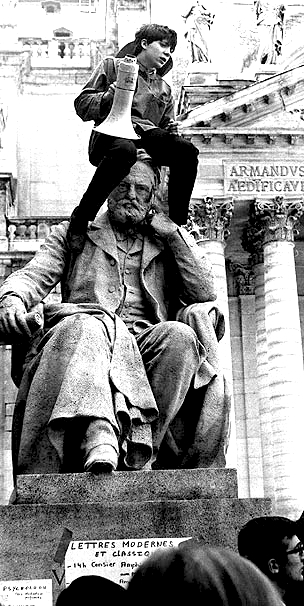

In Student Uprising, Sorbonne, Paris, 1968, Shumsky shot a triumphant female student protestor who was addressing an out-of-frame crowd with a megaphone. She had climbed the Laurent Honoré Marqueste’s statue of Victor Hugo in front of the Sorbonne. In Shumsky’s representation, the student dismantled one of the patriarchal symbols of the French Republic by irreverently climbing atop and stepping on a French literary icon. Flavia Rando writes in her introductory essay to Portrait of a Decade that “with this photograph, we sense a shift in Shumsky’s perspective, the visual field has altered, space changed, she becomes the audience that is exhorted. Once at a comfortable distance, the viewer’s response is now demanded and we become necessary participants.” In this tableau, Shumsky frames with her camera an equivalent to the familiar theatrical representations in Les Misérables of revolutionary uprisings. However, while capturing the universal struggle of protest against authority, this image has further gender significance by making the protagonist a woman. Indeed Shumsky focuses her camera largely on women, aligning herself with the tradition of female artists who challenge the hitherto dominant male representations.

The Stonewall Riots were a coming of age, a turning point, making activists of many, and the event sent shockwaves not just through the United States, but around the world. For Shumsky, an afterimage of rebellion remained in her mind’s eye, smoldering. She returned to Paris, having witnessed during her neighborhood walk the aftermath of gay people fighting for their rights. Friends sent her compelling letters from the U. S. about a burgeoning new movement. She returned home. In her walk-up apartment, she built a darkroom and committed herself totally to gay liberation. When reflecting on the early years of her photography, Shumsky appreciates that her “life was really organized around a search, not always conscious, for self-delineation.” Her lesbian identity was fractured, and she was at the threshold of a creative life that was full of inchoate yearnings, at once motivated by a historicizing impulse to capture a political movement and the incumbent events that shaped it, and painfully aware of her need to search for an identity and to become more self-aware.

“I was never without my camera,” Shumsky recalls. Her camera was integral to her identity and symbolized her evolution into a unified self. Photography set into motion a creative and personal odyssey that spanned a decade. Her images reflect a historical awareness during the turbulent 1960’s and 70’s, with a special focus on the development of the GLBT movement. And they narrate her personal journey. Shumsky discloses: “I was very alienated from myself. As a female and a lesbian, growing up in the 40’s and 50’s, I was the child of my parents and their particular history and culture.”

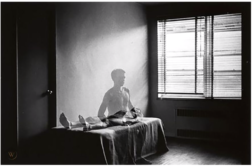

The intimate and seemingly private moment between two women (left) illustrates an æsthetic shift in Shumsky’s work as she embraced the feminist and countercultural maxim that “the personal is political.” In addition to redefining masculinist interpretations of “the political,” this image of lesbianism riffs on the documentary genre, which is usually associated with public spaces, by collapsing any notion of private versus public. The recognition of lesbian identity occurs on the threshold between private and public space. Shumsky pulls her subjects into the frame, turning a private moment into an image so close up that it bursts its frame, making it part of the public record.

An essential legacy of early gay liberation was the transformation of “coming out” from a private and personal experience into a political strategy. Shumsky makes a point of shooting out-in-the-open GLBT people, leaving none of the traditional ambiguity, producing images of unequivocal candor. Her role as photographer corresponds to that of social commentator with subjects that are more archetypal than individual. By bearing witness during the early years of gay liberation, she presents herself not as a casual bystander, a remote witness, but instead as an involved participant. Thus she satisfied the moral obligation of both a documentarian and a lesbian activist.

In “Radicalesbian Commune” (above), the Radicalesbians, an offshoot of the early gay liberation movement after Stonewall, have taken to the countryside. Only a year after Stonewall, they’ve created a living space for lesbians that brims with new possibilities. Rural communal life with alternate forms of bonding and intimacy and the effort to create egalitarian relationships is seen to transform urban lesbian amazons into a community of rural separatist utopians.

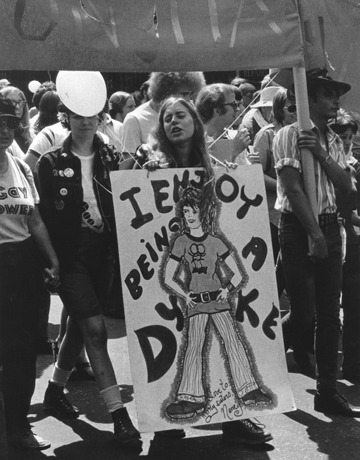

In the photograph below, Shumsky represents the lesbian persona, not to invalidate or overturnsexist and heterosexist assumptions, but rather to validate the concept of lesbian identity. She didn’t address notions of so-called normality; her intent was instead to make lesbianism visible.

Shumsky’s photographs construct identities, and above all they portray lesbians on the cusp of a new political movement. She is unassuming about their political importance, noting: “You may observe that my interest was almost exclusively in people—many of my photos are, in effect, candid portraits.” But her subjects are far from prosaic portraits or stereotypical figures of female exploitation or victims of oppression. Always aware of gender, she shoots a subject at a the first Gay Pride March in 1970 who is parodying the well-known Rodgers and Hammerstein song, turning it on its ear with the rejoinder, “I Enjoy Being a Dyke” (below).

After Stonewall, a shift took place in the perception of reality so persistent it radically altered assumptions about gender and sexuality. Photographs were the manifestos from underground, documents that subverted established constructions of identity and sexuality. Documentary photography always maintained a powerful claim to truth. The importance of affirming the early social documentations can’t be overstated. Renowned documentarian Dorothea Lange observed that “the camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” For Shumsky, making photographs was revelatory and she experienced many epiphanies on her photographic journey. But, when Shumsky’s cameras were stolen in the early 1980’s, she chose not replaced them. She was whole and the transition was complete.

Steven F. Dansky, a writer and photographer, curated the exhibit “Gay Liberation Front (1969-1971): A 40th Anniversary Retrospective.”