PHOTOGRAPHY is not simply a reproduction of the real. Its objective is not merely to report but also to enhance visual experience, feeling and emotion, ritual and response, and to change the way we see the world. Regardless of the camera technology, the creative intent of photographers has always been to stir the imagination, to tell a narrative of place, history, and memory, and to apply the force of evidence to its subject. Throughout the history of photography, images have made the invisible visible—whether the 19th-century Civil War battlefield scenes captured by Mathew Brady, Nick Ut’s photograph of a nine-year-old girl aflame from napalm during the Vietnam War, or more recent snapshots of torture by Americans at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

The challenge for photographers faced with portraying the AIDS epidemic was to produce an iconography that extended beyond a health story and to overcome the public’s habituation to graphic and shocking images. The photographs selected for this essay had to evoke the mood of the late 1980’s and early 90’s and capture the epidemic in the imagery of contemporary culture. The images reflect that time frame and are not meant to discount other periods in the epidemic.

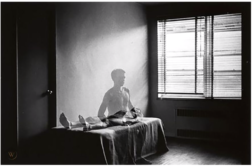

Arthur Tress’s constructed photograph, “Blue Collar Fantasy” (Fig. 1), is an elaborate tableau that typifies his exploration into the aesthetic potential of photography. The photograph examines the conjunction of desire and the reality of the epidemic. Wrote Tress, whose photographs are included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Photography is my method for defining the confusing world that rushes constantly toward me. … It is my defensive attempt to reduce our daily chaos to a set of understandable images. … I need it to survive.”

The human body has never seemed as fragile or tortured as it does in Alon Reininger’s portrait of “Kenneth Meeks” (Fig. 2), photographed in extremis. A member of the board of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), Meeks’ death occurred only days after this photograph was taken. The image portrays the trauma and disfigurement of Kaposi’s sarcoma with the purplish lesions that brought social stigma and were a constant visual reminder of HIV infection. Reininger later commented: “I flew to San Francisco, at my own expense and went to see him. I didn’t wait for an assignment. It was too difficult to get anything on AIDS published at that time, period—much less an assignment. Most of the editors were straight people who managed to dodge, for the most part, this whole crisis.”

Commenting later on the early years of the epidemic, photographer Nan Goldin wrote: “About ’85, I realized that many of the people around me were positive. … I was in denial that people were going to die. I thought people could beat it. And then people started dying.” Her photograph, “Gotscho Kissing Gilles, Paris, 1993” (Fig. 3), is a touching depiction of tenderness between lovers and exemplifies the theme of intimacy that operates in much of Goldin’s photography. The picture is part of a series that she made in 1992 and 1993 of Gotscho supporting his lover Gilles until the latter died from AIDS. This photograph reveals what had been banished to the private realm, making public an intimate moment of same-sex relatedness.

Duane Michals wrote that his photographs are not meant to “tell you what you can see, rather to express what is invisible. I write to express these feelings. We are our feelings. Photography deals exquisitely with appearances, but nothing is what it appears to be.” His “The Dream of Flowers” (Fig. 4) epitomizes the universal themes that are common to Michals’ work: love, desire, memory, death, and immortality. The surrealist, faun-like young man whose head, resting on a glass table, gradually obscured by cut flowers, cinematically depicts the theme of loss that came to represent the pathos of the epidemic.

Of his untitled self-portrait (Fig. 5), David Wojnarowicz wrote: “I buried my face in the earth of Chaco Canyon” in the northwest corner of New Mexico, which is carved from ancient sea beds with millions of years of history revealed in layers of rock and embedded fossils. In this self-portrait of being buried alive in crumbling dirt, eyes closed and mouth open, Wojnarowicz seems to represent himself as re-emerging, in the throes of an initial stage in some process, rather than as a portrait of death and finality. (Last October, “A Fire in My Belly,” David Wojnarowicz’s four-minute video, was removed from the Hide/Seek exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. See Kat Long’s article in this issue.)

The first word in Homer’s Iliad is the Greek word menin, which means wrath, rage, passion, an “anger that stores itself up for a long time.” With the founding of ACT UP in 1987, this kind of anger came to define the response to the epidemic. Larry Kramer posed the question to an audience at New York’s LGBT Community Center: “Do we want to start a new organization devoted to political action?” Two days later, 300 people met to form ACT UP. Kramer’s leadership, activism, and writing have brought more attention to the hiv/aids epidemic than the efforts of any other single individual. ACT UP embraced public performance as a vehicle to express and advance a political agenda. In December 1989, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the group protested John Cardinal O’Connor’s homophobic and anti-choice statements, making headlines in newspapers and television stations in New York, after over a hundred demonstrators entered the cathedral and were arrested. The Times estimated that more than 5,000 people demonstrated outside the church.

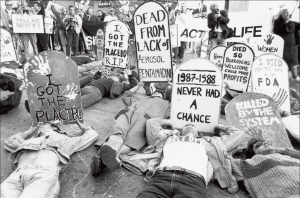

Of his photograph “Every Half-Hour” (Fig. 6), Marc Geller wrote: “It’s from the protest at FDA in D.C. October 1988. It was a mad scramble of protests and civil disobedience (FDA, HHS, and Supreme Court) along with the somber first big display of the Names quilt. Or have I conflated what seemed like one protest without end for years?”

Peter Ansin, a former manager of business development for Twentieth Century Fox, died of AIDS at 34 in 1992. The Ansin Building in Boston is the largest facility ever constructed by an organization with a specific mission to serve the LGBT community. It was dedicated in memory of Peter Ansin. His photograph (Fig. 7) of the ACT UP demonstration at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), outside Washington, DC, on October 11, 1988, shows street performance at its best. The demonstration closed down the FDA to protest the slow process of drug approval. They argued that because HIV was an incurable disease, new drugs should be reviewed as quickly as possible. After countless protests, the FDA eventually streamlined the review process for key HIV medications, including AZT, and within a few years introduced rules to fast-track approval for drugs.

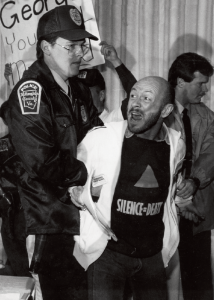

Patsy Lynch, who has been working as a photojournalist for over twenty years, photographed Brent Earl Nicholson being arrested by Arlington, Virginia police for trying to blockade an AIDS conference addressed by President George H. W. Bush (Fig. 8). Nicolson is wearing a T-shirt with the familiar “Silence = Death” logo. Of the demonstration, he later wrote: “We took over the hallway leading directly into the conference and managed to distribute the flyers to practically everyone who entered the conference. We’d been there almost an hour before a hotel manager finally showed up with the cops and made the expected pronouncement that we had to leave and that if we didn’t we’d be arrested for trespassing. … I wasn’t going anywhere until I was able to deliver my letter to President Bush and to find out what he was going to do about AIDS in America.”

During the first decade, photographic representation of hiv/aids often featured portraits of ravaged and hopeless victims, but in the 90’s there was a philosophical shift along with medical advances. People were living with HIV rather than inevitably dying from it. This changed perspective is evident in the photographs of Thomas McGovern, who commented on his photograph “Leslie King” (Fig. 9): “[It] shows Leslie in her Brooklyn apartment standing next to a memorial for her deceased friend Michael. As her T-shirt claims, she did indeed have a Brooklyn attitude!” In his photographic monograph, Bearing Witness (To AIDS), he wrote: “While I have photographed many aspects of the crisis since 1987, it is the portraits of people with AIDS that are central to this project and it is around these that the photographs of events revolve.”

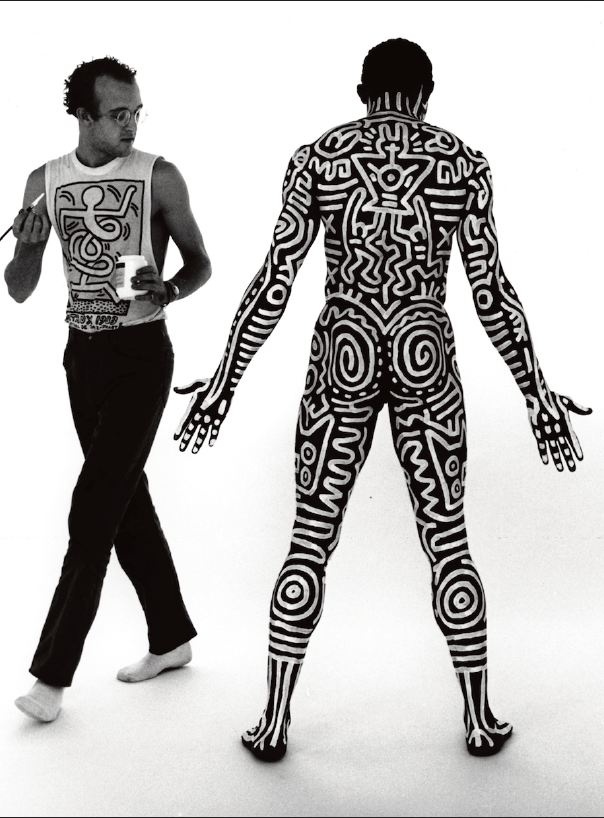

Tseng Kwong Chi, 1983. Estate of Keith Haring.

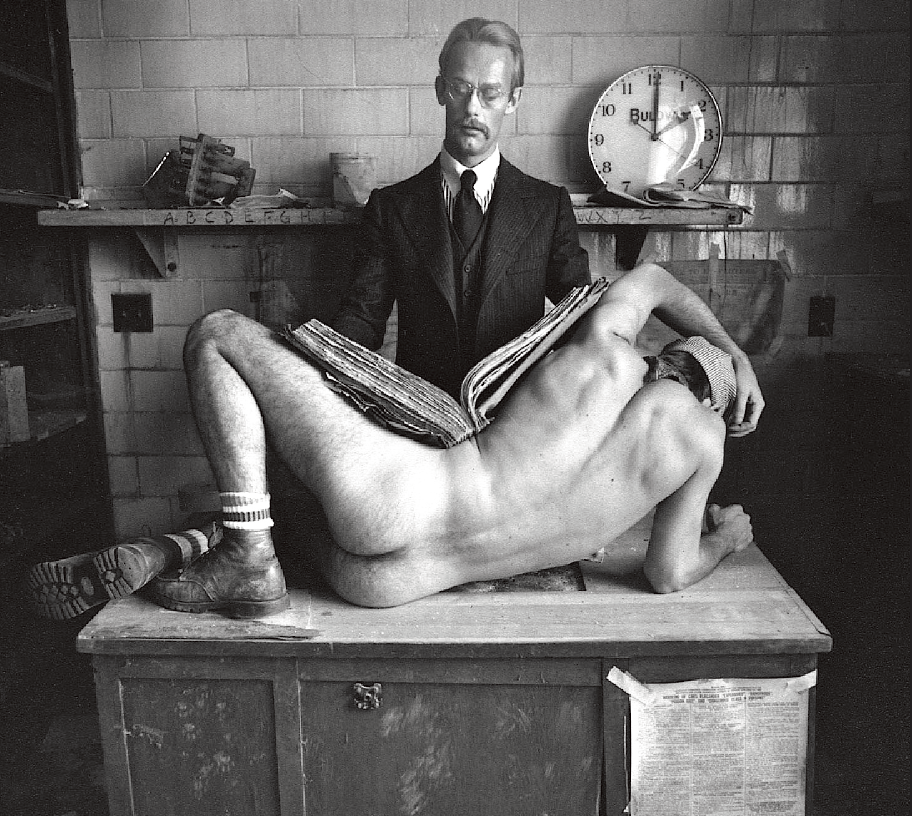

In Jon Gruen’s Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography, artist and social activist Haring said of his meeting Tseng Kwong Chi that “he was standing on a street corner on First Avenue and Fifth Street. He was wearing these really high white corduroy pants. He was so eccentric looking that I knew I had to meet this person. I ended up sort of cruising him, and we became friends.” The two artists collaborated on the photograph of the award-winning choreographer Bill T. Jones (Fig. 10). Tseng Kwong Chi took the photograph, and Haring provided the full-body painting of Jones, who said of the photo shoot: “It took so long! Over four hours! And the white acrylic paint was so cold! I suddenly felt what it must be to be a bushman! I was transformed, because as Keith was painting me, I moved almost constantly—I followed Kwong Chi’s instructions, because he was photographing me from every possible angle. … They’re a great record of a great moment!”

In No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites proposed that “Iconic images are emotional because they are born in conflict or confusion.” Controversy generates censorship. The hiv/aids epidemic has been and still is a phenomenon of great significance and manifold meanings, touching on sexuality and social structure, arts and culture, sexuality and taboo, plus issues of religion, celebrity, business, and politics. The semiotic and societal complexity of the epidemic are apparent in light of these images.

Steven F. Dansky, a writer, photographer, and political activist for a half-century, has written two books on HIV/AIDS.