AS A CHILD I was a chameleon, a subterranean queer kid whose favorite book was The Story of Ferdinand, about a bull who preferred to sit among flowers rather than fight in the arena. I learned to lie low, watch, evade, fantasize, get by, fool myself, fool others. I became a teenage loner absorbed in playing classical piano, ostracized for being queer during my senior year in high school. I never spoke my mind. Getting away to college changed all that.

In May 1965, at the end of my sophomore year at the rebellious UC-Berkeley, I leaned against the dorm payphone. My hand shook as I held the receiver while my father chewed me out. I knew my mother was listening, but she said nothing. “We’re paying for your college education so you could become a professional, not an agitator. Is this how you show us thanks?”

“I’m not being ungrateful by standing up for what is right,” I snapped back. I was proud that my deep alto voice didn’t sound weak or apologetic as the conversation shifted to our usual argument about the Civil Rights Movement. I bristled when he used a pejorative Yiddish term used to demean black people. My father didn’t care about equality.

He had all that he wanted in the myopic ’50s—the latest TV set, vacations abroad, a big house in an all-white neighborhood. Well, fuck that! My generation was getting down, getting high, getting busy with confronting this country’s longstanding injustices, like racial segregation and the shameful war in Vietnam. Like many in my generation, I wasn’t going to play by my father’s rules any longer.

He’d finally had enough of me, asking: “When are you coming back for the summer?”

At last the chameleon found her true voice. “I’m going to Minneapolis. I’ve met someone I want to be with, someone I love. Her name is Catlin.”

He exploded, calling me a child, an infatuated fool. He said next week I’d fall for some boy, and this silliness would be over. It hurt to hear this, but it didn’t change who I was or whom I loved. When he realized that this tactic wouldn’t work, he told me to come home or he’d cut off all financial support. I was staggered that he was going to push right to the edge. I expected my mother to intervene, but she didn’t. Did I ever really know them? I wondered.

“Send my tuition to the Vietnamese,” I yelled and hung up.

That conversation utterly changed my life. Suddenly I went from a sheltered, dreamy child to a struggling adult, a would-be lesbian of conscience. I didn’t crawl back to safety, to my father and his money. Instead, I scraped by, sometimes barely eating enough, supporting myself with odd jobs, and ultimately graduating with honors.

Rather than accept my diploma in front of a sea of proud strangers, I left for Chicago in June 1967 for a summer of anti-war organizing. I ended up working for a pacifist social action organization established by the Quakers. My job was to help young guys file as conscientious objectors, an impossibly tough process that spared few from the Army and Vietnam.

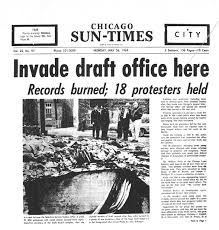

One May night in 1969, along with seventeen others, I broke into the Selective Service office in Chicago’s South Side. We stuffed over 40,000 draft records into sacks, dragged them to the adjacent parking lot and set them on fire. We selected the South Side, the urban epicenter of a large black community, to make our statement about the Vietnam War and racism. I knew then that I would never meet the guys whose files we destroyed, but I still hold onto the hope that they never were drafted, never lost their lives in some paddy field in Vietnam.

My decision to burn the draft files set me on collision course with the government for many years, nineteen of which I lived underground for fear of arrest. I was never captured; rather, I voluntarily surrendered in 1989, because living an alias existence, however successful, wasn’t a viable life.

At 74, I haven’t renounced the heresies of my youth. Rather, I embrace my ideals, even though I admit it was damn rough for years. Now, like everyone else, I find myself in the midst of a global pandemic. The lessons I learned while underground and the resilience I developed when cast off by my parents have helped me stay strong in the face of the pandemic.

Words can’t adequately describe the restlessness and inner turmoil many of us feel as we shelter in place. We have to struggle with the recurring sense of mourning for our old lives and routines, which seem to be disappearing in the rearview mirror, ever smaller, the details becoming indistinct as we tick off the days since this invisible killer came to our shores. I know down to my bones what it’s like to feel that way, to feel awash and divorced from who you once were.

My life has taught me to risk being myself, to hold onto my ideals, to be mindful, to find a way, rather than wait for “normal” to return. Mindfulness is about being grateful and present in the moment, an inner voyage connected to ourselves, our gender identity, and the natural world. Through mindfulness, I’ve found a path that allows me to feel centered no matter what occurs beyond my control. That’s what led me at last to my true home, my Ithaca.

Emily L. Quint Freeman is a lifelong activist and author of Failure to Appear: Resistance, Loss, and Identity, A Memoir, Blue Beacon Books. She has been interviewed in national/local media and published pieces in venues like Narratively and Salon. When she isn’t writing, you might find Emily planting veggie seeds in her garden or at her piano playing Scriabin. Learn more at: www.emilyqfreeman.com or her Facebook Group “100 Seconds to Midnight Notebook.”

Emily L. Quint Freeman is a lifelong activist and author of Failure to Appear: Resistance, Loss, and Identity, A Memoir, Blue Beacon Books. She has been interviewed in national/local media and published pieces in venues like Narratively and Salon. When she isn’t writing, you might find Emily planting veggie seeds in her garden or at her piano playing Scriabin. Learn more at: www.emilyqfreeman.com or her Facebook Group “100 Seconds to Midnight Notebook.”