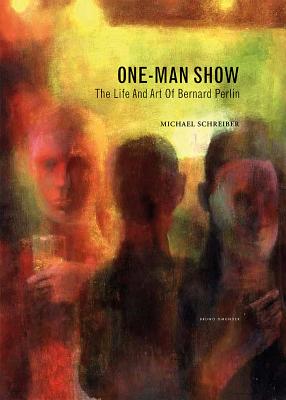

One-Man Show: The Life and Art of Bernard Perlin

One-Man Show: The Life and Art of Bernard Perlin

by Michael Schreiber

Bruno Gmünder. 256 pages, $59.99

ANY LIST of important gay male artists of the mid-to-late-20th century would probably include names like Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes, and David Hockney, to name just a few. But while the list could be quite long, it’s doubtful that artist Bernard Perlin (1918–2014) would make the cut. Known and admired by all of the men listed above, and many others, Perlin never earned the kind of fame that most of his contemporaries enjoyed. He did, however, enjoy financial and critical success. When he was in his thirties, the Tate acquired one of his paintings, and his work was consistently popular and well-received throughout his career.

Michael Schreiber’s One-Man Show is an exhaustive chronicle of Perlin’s life and work