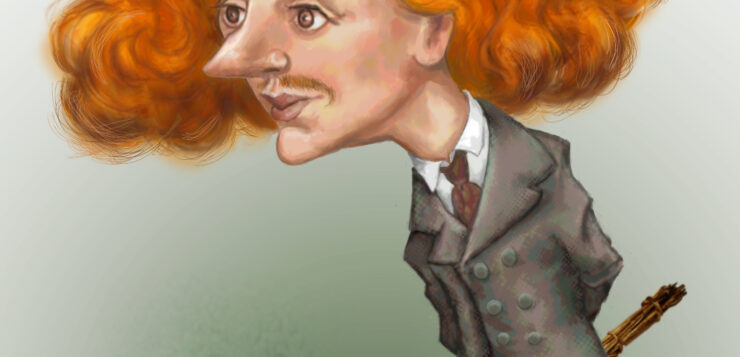

THE POET Algernon Swinburne (1837–1909) can be best described as a colorful eccentric who lived and wrote without shame in late Victorian England, where moral behavior was so strictly regulated that artists with bohemian ideas were performing incredible stealthy feats in order to launch their careers. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood paid for and hosted their own exhibitions of original paintings when the established salons refused to entertain their too-realistic biblical scenes and brazen red-headed women in striking poses. Swinburne, perhaps inspired by his friends at the Brotherhood, defied his age entirely when he decided to write a poem about a romance between women.

In the 19th century, lesbianism was a taboo topic on a par with bodily functions. Even the landowner and traveler Anne Lister (1791–1840), a notorious seducer of women, recorded her private diary in a complicated secret code. It’s not an accident that her diaries ended up stashed in a wall for years, read by no one. But the educated elite of Victorian England also had a convenient historical smokescreen behind which they could veil their ventures into lesbian themes: Sappho of Lesbos, the great poet of Archaic Greece and an admirer of women.

In the time of Swinburne, Sappho’s existence was something of an inside joke among the cognoscenti, which included historians, theater people, and literary types, especially those who had similar predilections to those of Sappho.

In the time of Swinburne, Sappho’s existence was something of an inside joke among the cognoscenti, which included historians, theater people, and literary types, especially those who had similar predilections to those of Sappho.

Emily R. Zarevich is an English teacher and writer from Burlington, Ontario.