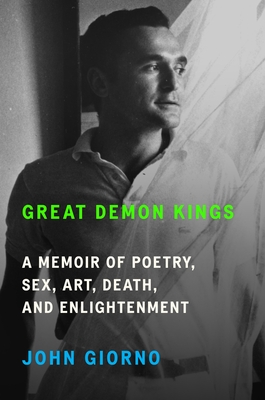

Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment

Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment

by John Giorno

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

368 pages, $28.

FROM THE START, John Giorno wanted two things in life. In 1958, “I was young and beautiful and that got what me what I wanted and all I wanted was sex,” he recounts in his post-humously published book, Great Demon Kings. What we learn early on in this royal paean to the self is that Giorno (1936–2019), who was a poet, an artist, and an activist, had an insatiable appetite for fame. Upon reading this memoir, one realizes that he possessed a surfeit of libido and ego, in addition to a talent for befriending talented people, to launch him toward this goal.

In a moment of false modesty, while being “sucked off,” as he so poetically phrases it, in a New York City subway station restroom in 1982 by a “young, slightly homely but still cute kid wearing wire-rimmed eyeglasses,” he came to realize that “the kid recognized me as the poet John Giorno. This was always disappointing, because it compromised the spontaneity arising in play where there was no past, present, or future, only bliss continuously coming.” Whatever he means by that, the punchline to this incident is that the 24-year-old kid was the budding artist Keith Haring.

So influential did Giorno believe he was in all arenas of New York life that, years later, after he and Haring had become friends, the poet says of that encounter amid the stench of urine: “Of the countless great sexual encounters in the golden age of promiscuity, that one always symbolized all the others. I believed we were the combat troops of love liberating the world.” Apparently, up until the early 1980s, love had all along had a different significance until Giorno’s and Haring’s ejaculations as they awaited the A Train.

It’s hard to like Giorno in this book due to his outsize ego and conceit. But it’s easy to enjoy the book because of the life he managed to construct for himself. A Zelig figure, he managed to meet (and bed) seemingly everyone of note from the early 1960s through the ’80s. While he never hooked up with Dylan Thomas, he was “anointed” by beads of sweat from the great Welsh poet during a live reading, later running into the bard, chastely, in a restroom. From Giorno’s youthful days soon after graduating from Columbia University in 1958, he seems always to have been in the right place with the right people—and getting the desired response from them, usually physical attraction. His address book was filled with the likes of Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Salvador Dalí, and the Dalai Lama.

While few of Giorno’s poems are included here, he admits that many of his works are “collages of found images.” With scissors and tape in hand, he would dissect existing texts to create works under his name. One of the pieces he includes in the book is his 1965 “Pornographic Poem,” composed of words from what he calls “a mimeographed erotic story that I don’t know how I had gotten my hands on.” With most of the lines composed of a single word, this hardcore poem dribbles down the page to recount a fantasy encounter with seven Cuban army officers. He claims that the poem was a “cause célèbre” of the time. Whereas Burroughs’ Naked Lunch was being debated as obscene by the Massachusetts Supreme Court, he states, “‘Pornographic Poem’ was admired by all the poets on the Lower East Side, Andy [Warhol] and the Pop artists, and the art world.”

Giorno did create some literary moments, notably his revolutionary “Dial-a-Poem” program. In 1968, he harnessed the new technology of answering machines to record famous poets of the day reciting a poem. Callers would dial in to hear Giorno, Ginsberg, Kerouac, Jim Carroll, and others read a poem. So popular was the call-in service that circuits were overwhelmed at certain times of the day in New York. “As a curator, my personal favorites were poems with sexual images, particularly gay,” writes Giorno—which proved the demise of the service, since schoolboys called in regularly to hear lines about glory holes and “erect pricks.” Eventually, the phone company disconnected him.

John Giorno does not come across as a thoughtful or terribly original writer of poetry or prose, but he was clearly a resonant personality of his time and place in New York. Even though this memoir is a work of nonfiction, it does have a plot, that hinges mainly on the title reference to “demon kings.” Without giving it fully away, we learn on the very last page what he means by that egocentric phrase. In that sense, he was and probably remains the once and future king.

David Masello is an essayist, poet, and playwright who lives in New York City.