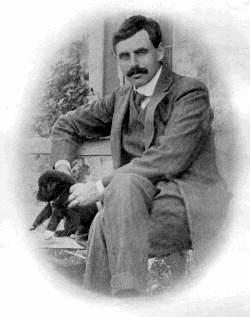

I HAVE recently discovered a poem titled “The Ballad of the Student in the South,” by James Elroy Flecker (1884–1915). He is a lesser-known British poet who, despite the year of his death, did not perish in World War I, as did so many of his poet peers (Rupert Everett, Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg, and so on). He died of tuberculosis, in a sanitarium in Davos, Switzerland.

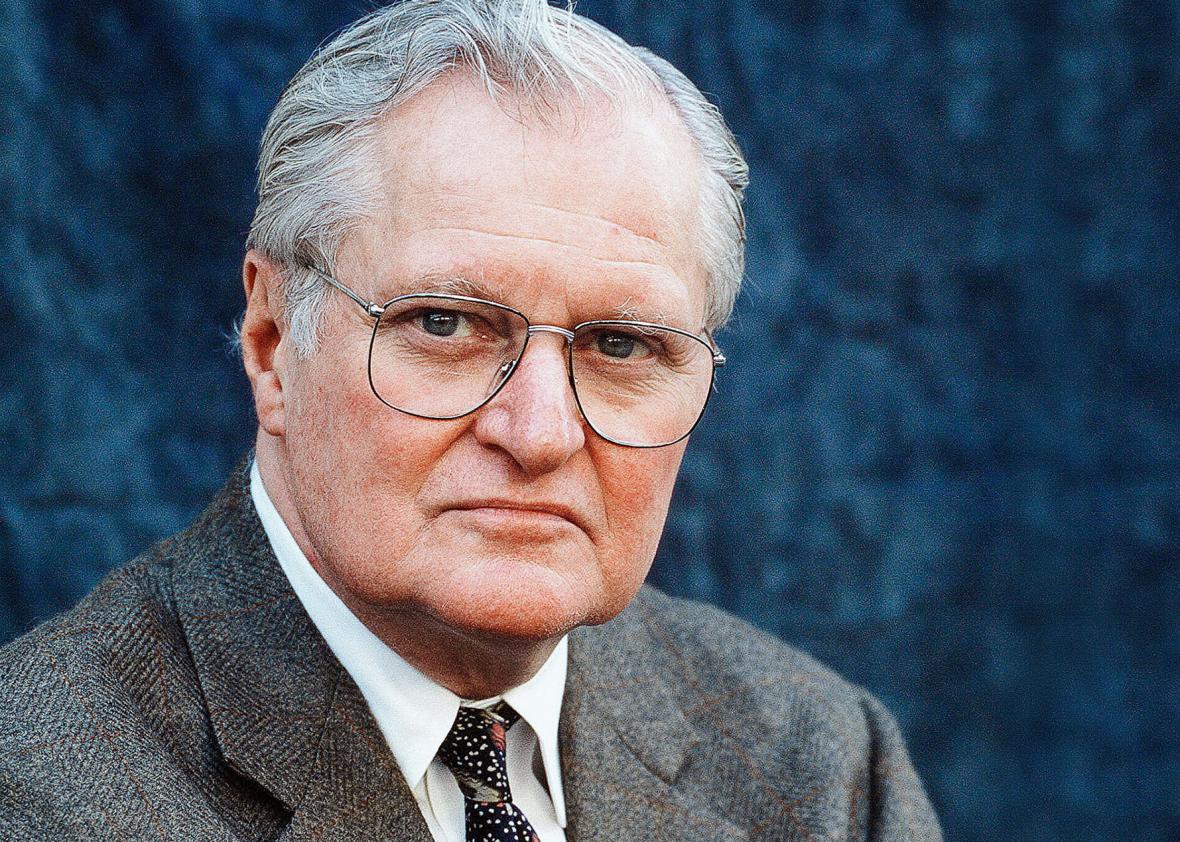

I came across Flecker while doing research on a classmate of his, a Sir John Beazley, who became the world’s foremost scholar on Greek vases, having devised ingenious ways to identify certain anonymous ancient painters by the simplest of their painted details—the folds of a toga or the curl of the eyelashes, perhaps, on the surface of a bowl or cup. Among Beazley’s discoveries was an artist he later referred to as “the Berlin Painter,” named for an amphora in the collection of a museum there. Beazley and Flecker were college chums at Oxford and lovers too, or so it has been surmised. They remained in contact steadily until Flecker’s untimely death.

I came across Flecker while doing research on a classmate of his, a Sir John Beazley, who became the world’s foremost scholar on Greek vases, having devised ingenious ways to identify certain anonymous ancient painters by the simplest of their painted details—the folds of a toga or the curl of the eyelashes, perhaps, on the surface of a bowl or cup. Among Beazley’s discoveries was an artist he later referred to as “the Berlin Painter,” named for an amphora in the collection of a museum there. Beazley and Flecker were college chums at Oxford and lovers too, or so it has been surmised. They remained in contact steadily until Flecker’s untimely death.

Like so many men of that era who were homosexual, Flecker and Beazley eventually married women. In their youths, however, they pined for, pursued, and celebrated love with other young men. People like Flecker wrote ardently and shamelessly, even recklessly, about these love affairs. The fact that he—like other men such as Rupert Everett and Oscar Wilde—was able to lead a largely heterosexual life, fathering children and staying married for decades, has always confused and perplexed me. Perhaps some of these guys really were bisexual, a state of being that in my experience is relatively rare among men. Perhaps their unions to women were “marriages of convenience” to satisfy social expectations, or perhaps they succeeded in genuinely deluding themselves.

When I first read Flecker’s poetic ballad, I knew without any gender reference that he was addressing a young male. “It was no sooner than this morn/ That first I first found you there,/ Deep in a field of southern corn/ As golden as your hair.” And: “For we are simple, you and I,/ We do what others do./ Linger and toil and laugh and die/ And love the whole night through.” Gay men today, and perhaps even back then, do often possess some extra sense when it comes to finding another of his kind. Often, we can sense from words or lyrics when the object of affection in a particular work is directed at another male. I think of this poem as a prime example of the “morning-after” poem, an unacknowledged genre in itself.

I have been reading a lot about Flecker: his travels as a young diplomat throughout the Middle East; his recurring tubercular episodes; the charismatic and devoted Greek woman, Helle Skiadaressi, whom he met on a cruise ship and whom he later married. (She died in 1961 and is buried alongside him in England.) I read a book she wrote and published in 1930 that recounts their brief marriage; she includes in it fragments of letters he had written to friends, as well as her remembrances about their relationship and travels as husband and wife. She includes one letter that Flecker had written to a close friend of his. In it, Flecker laments not being able to see his wife for an extended period and how he dreads the prospect of having to be “celibate” for the duration of her absence. So, it seems their marriage was a true union.

The moment in my freshman year of high school that I encountered Alfred Tennyson’s “In Memoriam,” I recognized it as a paean to a deceased male lover, despite much of the critical material I came across at the time that spoke of the poem as addressing the loss of a good friend. I have since memorized that poem (my only insecurity, when reciting it aloud, being whether to actually rhyme a couplet in which the end words are “again” and “rain”).

In researching Flecker’s brief, peripatetic life, I learned that he had taught at a public (private in England) school likely when he wrote this poem; it is included in his one of his books, Thirty-Six Poems(1910). His students, likely sixteen and seventeen years old were just several years younger than he and I suspect this poem might have been about one of them, for, as he writes in the poem, “I had read books you had not read,” and a couple of stanzas later, he states, as if emphasizing his own teacherly status in comparison to that of the student, “Darling, a scholar’s fancies sink/So faint beneath your song.”

He asks, rhetorically, within the work, “Shall I forget when prying dawn/Sends me about my way,/The careless starts, the quiet lawn,/And you with whom I lay?” Clearly, this was about a love or deep lust, the memory of an encounter he meant to accompany him through life, even if it was never to be repeated.

Those fluid, bifurcated, enigmatic romantic lives so many men of that era led, will always confuse me. I’m not sure we today can ever fully empathize with them, though we can sympathize. Many men, such as Flecker, were productive writers, with profound talents for expressing their love through their art. Love—whether fulfilled, unrequited, or unfulfilled—is one of the choicest raw materials for art, the most reliable muse. These men didn’t have it as their mission to win over society or seek approval for their identities. To have been able to articulate their love, these men likely helped save themselves from despair, while also, perhaps, winning the objects of their adoration.

David Masello is a frequent contributor to The Gay & Lesbian Review.