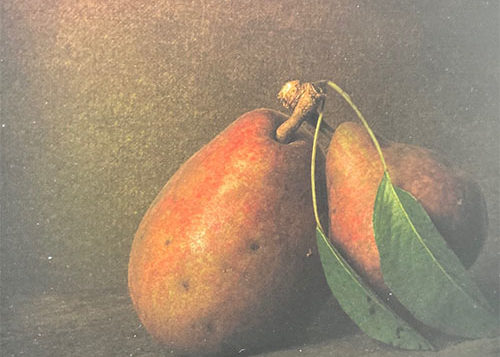

I have long wanted to live with a split pomegranate or raw oyster on the half shell, even a partially peeled lemon, whose rind corkscrews about the stem of a goblet of wine. I now live instead with yet another coveted element from that imaginary table of still-life objects typical of the Dutch Golden Age—a framed image of two golden-russet-colored pears, one whose stem remains affixed with leaves, as if the fruit has just been picked and left to ripen further. However, spots on the greenery indicate approaching decay.

Most of the elements arrayed on a tabletop in a Dutch still life carry a symbolic charge. Oysters and pomegranates and phalluses of dangling rinds connote sex, desire, fertility, while a skull or fly alit on a slice of mincemeat pie suggest mortality. Lobsters, wheels of gouda, gleaming pewter cutlery speak of the owner’s wealth. Pears might connote the sweet yet fragile nature of life and the bounty the earth provides. A pear spoils quickly, so enjoy the fruit once it has ripened; the sweetness that life often offers us is ultimately ephemeral.

Soon after I was given that image, I responded to its implied message.

The artwork, which measures a mere five-and-a-half inches square, is actually a highly manipulated photograph, the colors and resolution so transformed by technology by its artist, Sergio Villaschi, that his close-up assumes the presence of something painted on canvas. Akin to an act of alchemy that so fascinated the Dutch centuries ago, my contemporary photo has become a golden painting.

The work was given to me by a friend as a birthday gift. The moment I opened it in my dimly lit elevator on the ride up to my apartment, I loved it—not only for its beauty and its reference to the Dutch vanitas genre, but also for the symbolic import it carries about my friend and how the nature of our friendship might be shifting.

This is a friend I have known for four years, and who over the last year suffered significantly during the pandemic. He became sick with the virus, and he retreated into his apartment for many weeks. He has recovered—mostly, though odd symptoms linger, despite his being fit and hardly old. So affected was he by his infection that he has been questioning his life here in New York and whether he should move elsewhere to try something new.

“I know you and I know what you like,” he said, upon handing me the wrapped gift in a restaurant on West 42nd Street, where we were seated at an outdoor table to hear a cabaret singer at a piano inside. “Open it later.”

Because all of us lost a year of our lives during the pandemic, this birthday was the first about which I didn’t obsess or worry beforehand; I let it happen without objection. I was grateful to be alive, as any of us are who made it through, physically and mentally. And during all that time alone, inside, I was now out and celebrating with friends. At intermission, the singer, who I know, asked me to name a favorite popular standard. In a panic, I mentioned a song I like, but wouldn’t put at the top of my list.

“‘The Man that Got Away,’” I said, regretting my choice immediately. Too much of an antiquated “Boys in the Band” kind of anthem, I thought. But he played it for me and acknowledged my presence to the audience on my birthday.

I don’t remember ever telling my friend about my love of the Dutch Golden Age. He has seen the artworks that fill the walls of my living room—all figurative, realistic paintings—and, perhaps, extrapolated from that.

When I had unwrapped the work, I said to myself: “At last, I own a version of a Dutch still life.”

Villaschi has titled the work “Two Leaves,” written in ink on the paper backing. His naming immediately shifts the viewer’s focus from what seems to be the main elements in the work, the pears, to details ancillary to them. What might go largely unexamined are made the focus simply by his title. While those leaves taper elegantly, they register decay, a foil to the healthy luster of the fruit.

Shortly after my friend gave me “Two Leaves,” he came to dinner and was thrilled to find the work already hanging in my kitchen. I showed him the other places in my apartment I had considered displaying it—balanced atop a desk, on a living room wall already filled salon-style with paintings, over the TV.

“I wanted a spot where I would see the work first thing every day,” I told him.

That night, during our dinner on the roof of my building, 35 stories up, our glass beakers filled with wine, amid gusts of wind and the lit grid of Manhattan, the nature of our friendship shifted. Never before has a friendship of mine morphed into intimacy. I question whether what happened between us was a mere temporary change, akin the photographer being able to readjust his medium.

I think gay men have an extra keen olfactory sense (and given my Italian–Jewish heritage, a look at my profile bespeaks my extra special sense of smell). Many of us have a pronounced and professed desire for the scent within the cavity beneath an arm, the musk of a foot, an earthiness that arises from ruffled hair, the subtle trademark trace of someone that emanates from a throbbing artery along their neck. A still life fools the viewer into thinking it is solely a visual presentation. But every item in a still life has a powerful scent—of the sea, of the earth, of the vine, of the field. And, so, to detect a scent of someone for whom you feel desire is a kind of infection. You are affected by that infection, even if the source of it is not present. The scent becomes a memory. My friend’s scent is now in me.

I like to believe the artwork inspired this change between us, even if it’s only for a while. The art any of us lives with, it seems, not only reflects us, but can also determine our behavior. Pets in our homes have this ability, so why not artworks? My friend, who had recently become more acquainted with mortality, gave me something he knew I would want in my life, something that represents the joy and the transience of existence. And, so, I read the message implicit in his gift and responded accordingly. No matter what he and I become or remain, my friend is not that someone who got away in the song that was sung for me on 42nd Street.

David Masello, a writer about art and culture, is based in New York City. Masello is a frequent contributor to The Gay & Lesbian Review.