UNDER COVER

J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity

Curated by Donald Albrecht

New-York Historical Society

May 5–August 13, 2023

WHEN a young man named Charles Beach showed up to an open model call for a print ad in 1900, the illustrator, one J. C. Leyendecker, hired him on the spot. Both men, each in his twenties at the time, probably recognized a kindred queer spirit, if not a visceral attraction, that would lead to a lifelong romantic and business partnership. The motives behind a show of Leyendecker’s illustrations at the New-York Historical Society (NYHS)—Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity—are far more ambiguous. We’ll never know whether readers of magazines and viewers of print ads of the era were aware of a homosexual current in his illustrations that to our 21st-century eyes seems obvious. Such is the conclusion of the show’s curator, Donald Albrecht, in his writings about Leyendecker. “I am not a historian of sexuality,” he remarks, “but my intention in this show was to present Leyendecker in a new light and in so doing to raise as many unanswerable questions as possible.” (Full disclosure: Over the years, I have come to know Donald Albrecht and have written about some of the exhibitions he’s curated, including his 2016 Gay Gotham and his 2011 Cecil Beaton: The NY Years, both at the Museum of the City of New York.)

Albrecht assembled nineteen of Leyendecker’s original oil paintings that were later translated into print ads and magazine illustrations, along with scores of other ephemera. (In some cases, the museum undertook the task of purchasing original magazine issues in which the illustrations appeared.) A majority of the paintings are on loan from the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, which had approached the NYHS with the idea of a full-scale show highlighting Leyendecker, whose studio was housed in what was then the Beaux Arts Studio Building on West 40th Street (it’s still there). However, he and Beach later lived in New Rochelle, a nearby suburb in Westchester County known in the early 20th century for its artistic community. The Historical Society decided to accept the paintings on loan, but with the idea to mount a show focusing on Leyendecker that adhered to one of their new directives: “to tell stories of Americans whose lived experience, though important and consequential to our history, is so often absent from textbooks in schools and colleges.”

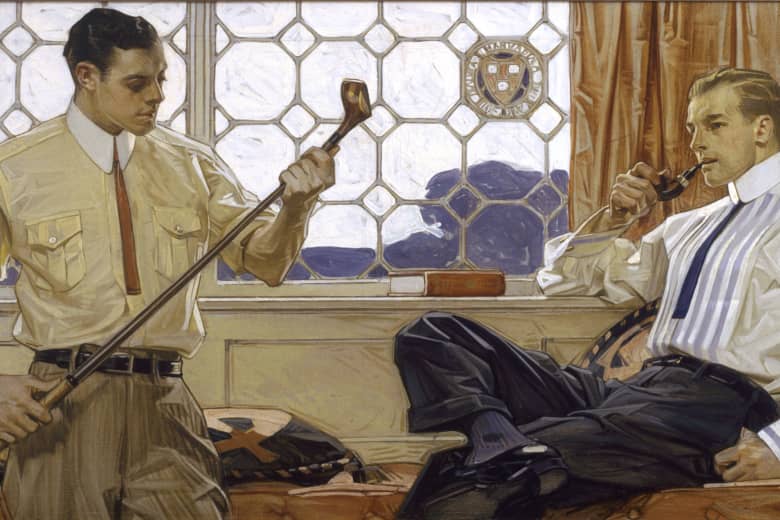

Leyendecker (1874–1951) was a prolific and much sought-after commercial illustrator for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and Cosmopolitan, as well as for print ad campaigns for companies that included Ivory Soap, Arrow Collars, and Gillette. What might seem to us now as deliberately provocative depictions of men alone and together were not perceived as such by readers of magazines in the early 20th century. For instance, are the two men that Leyendecker drew garbed in formal wear for a 1911 Cluette Dress Shirt ad leaning into each other to confer about stock prices or to assess each other’s value in other respects? Are the foppish pilgrim and statuesque off-the-field football player standing side by side for a November 1928 Saturday Evening Post cover about to share more than turkey and mincemeat pie? Is that upright golf club thrusting from one man’s midsection a coded reference to the other man admiring the club’s shaft in a 1909 illustration for Arrow Collar (one of the models for which is Beach)? And then there is that silver torpedo being thrust into artillery by a sailor whose lats, biceps, and delts are in full anatomical relief, as depicted in a 1917 cover illustration for Collier’s.

Part of the Historical Society’s decision to mount the show as it now exists was in response to a 2021 documentary, Coded: The Hidden Love of J. C. Leyendecker, which makes a convincing if circumstantial case that the illustrator purposely drew the images to convey homosexuality as a possible interpretation. Albrecht argues that the early decades of the 20th century were more receptive to images of masculinity and beautiful men in suggestively close proximity than we are today. “Leyendecker perhaps helped shape a different attitude toward masculinity,” Albrecht says, and he “was actually part of a Zeitgeist of the time when representation of men, of masculinity, of men’s behavior with one another was far more fluid that it is now. It was far less ‘binary’ then. Leyendecker was anything but alone because he was gay. He was part of a general trend.”

Albrecht underscores this point by including popular illustrations by other artists of this period, which reveal that Leyendecker’s versions of male beauty, while decidedly singular in style, were not so atypical. A 1928 Vanity Fair ad from the B. Altman department store by an unidentified artist shows two men, one reclined at the feet of another as they look adoringly at one another on a beach. Adolf Treidler’s 1926 illustration for Chesterfield cigarettes shows two top-hatted men-about-town, one leaning provocatively into the other to light his cigarette.

We tend to assume that positive gay-themed imagery is a phenomenon of the post-Stonewall world. But to look at these illustrations by Leyendecker and his contemporaries is to see overt depictions of sensual male beauty. A barely clothed young Yale man fills pails of water at the college boathouse; World War I soldiers on leave eye each other over a female figure at their center; a man languorously extends an outstretched gam à la Ann Miller as he admires his new pair of Interwoven Socks. We register these men as beautiful and sexy and often engaged with each other, but is it possible, as Albrecht emphasizes in his show, that ye olde times allowed for more suggestive images of men together and alone than we realize?

How refreshing to see an unabashed celebration of male, masculine beauty that was depicted long ago. Beauty is not entirely subjective; it has a universal dynamic. I think that gay men increasingly are under assault to cede our cultural and societal influence to every nuance of sexuality that someone else claims to possess. We are made to apologize for admiring, adoring, celebrating, even preferring that which is unambiguously male and masculine. Leyendecker clearly loved the faces and physiques of men, and he knew how to depict them with respect and awe, and with a sense of detail and personality that continues to enlighten, if not excite, us still.

David Masello, who’s based in New York City, is an essayist and feature writer on art and culture.