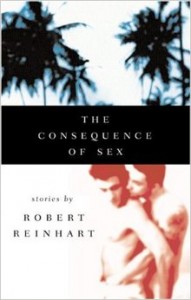

The Consequence of Sex

The Consequence of Sex

by Richard C. Reinhart

Alyson Books. 242 pages, $14.95 (paper)

FOR MANY of the characters in Richard C. Reinhart’s The Consequence of Sex, sex is an easy but ineffective salve for the twin pains of loneliness and despair. While its author doesn’t tend to moralize, The Consequence of Sex is aptly named. In many of these short stories, Reinhart explores the potentially devastating physical and emotional consequences of sex, or how the importance that’s attached to sex can undermine—or overwhelm—love. The stories are filled with one-night stands, prostitution, alienation, and rape, rendering all the more poignant those few moments that gesture toward real connection or even love.

The collection begins and ends with stories about despondent, aging men.