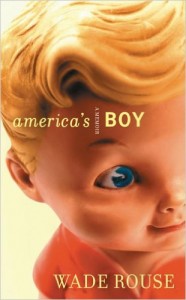

America’s Boy

America’s Boy

by Wade Rouse

Dutton. 340 pages, $24.95

THE CHALLENGE for any writer of a memoir is to make the story interesting to someone else who, unlike a psychotherapist, isn’t being paid to hear it. A writer’s fame can guarantee an audience, but those lacking fame often resort to hyperbole and sensational drama. This is not true of Wade Rouse in his coming-of-age memoir, America’s Boy. While the world may have seen plenty of coming-of-age and coming-out stories, there’s always something new to learn from a well-crafted and thoughtful account of this rite of passage. Rouse’s story is promising in that he has so many experiences to offer—including being gay in rural America, being (until recently) extremely overweight, and overcoming a devastating guilt about the death of his brother.