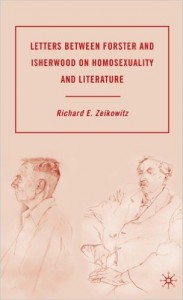

Letters between Forster and Isherwood on Homosexuality and Literature

Letters between Forster and Isherwood on Homosexuality and Literature

Edited by Richard E. Zeikowitz

Palgrave Macmillan

196 pages, $74.95

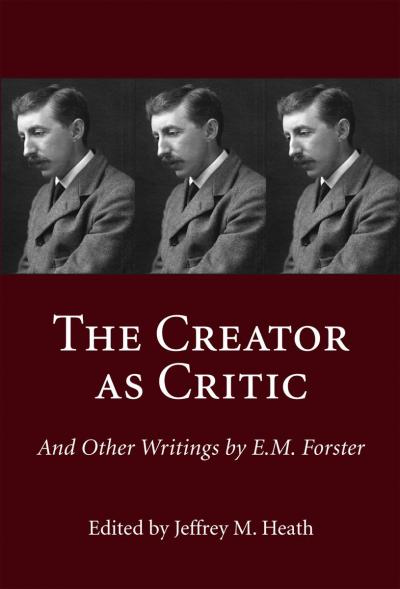

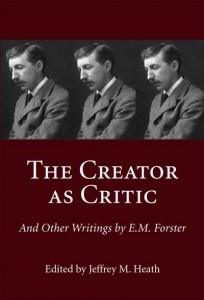

The Creator as Critic and Other Writings by E.M. Forster

The Creator as Critic and Other Writings by E.M. Forster

Edited by Jeffrey M. Heath

Dundurn Press. 814 pages, $90.

The BBC Talks of E. M. Forster, 1929-1960: A Selected Edition

Edited by Mary Lago, Linda K. Hughes, and Elizabeth Macleod Walls

University of Missouri Press

512 pages, $59.95

WHEN the English novelist E. M. Forster—“Morgan”—died in 1970, at the age of 91, the novel which, above all else, had cemented his literary reputation among the first rank of twentieth-century writers, A Passage to India (1924), was almost a half century old. Moreover, it was his last novel; in the intervening years, Forster had not so much renounced fiction as found he was incapable of writing it anymore. He told the public in 1958: “I somehow dried up.” Privately, he told friends he had run out of sympathy with heterosexual characters, storylines, the whole thing. Believing that for a man of letters it was “better to dribble than to dry up” (Frank Kermode’s phrase, from a recent review), he largely devoted himself to criticism. He also became, almost incidentally, one of the BBC Third Programme’s most recognized voices of cultural authority to listeners at home. He recorded just as often for the Corporation’s Eastern radio service, also known, cryptically, as “The Purple Network,” and broadcast to India (a colony until the end of World War II) and the Far East. For both services, he scripted a regular round-up of literary news (obituaries, chiefly), reviews of recent publications, and occasional puffs for old classics he liked or felt suited the times.

The whole enterprise of the Eastern Service embodied a colonial—then awkwardly post-colonial—ethos that the BBC embodied and which today would be unthinkable. In the dark years of the Second World War, Forster, living in London and experiencing the Blitz, loss, deprivation, and uncertainty very much at first hand, found himself airing scripts somewhat propagandistic in nature—though in saying this I’m adopting hindsight: such “slant” tended to go unquestioned, if not unacknowledged, in its day. Still, there is plenty of evidence of Forster as propagandist in the variety of BBC broadcasts transcribed and reproduced in two of the books here, Jeffrey Heath’s huge The Creator as Critic and the more focused BBC Talks of E. M. Forster, 1929-1960. These may well surprise those who recall Forster’s famous dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”