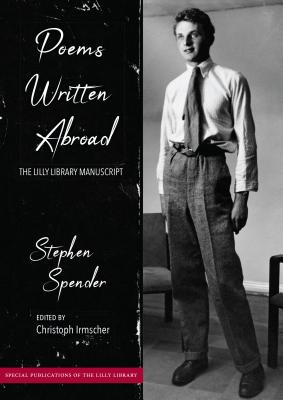

Poems Written Abroad: The Lilly Library Manuscript by Stephen Spender

Poems Written Abroad: The Lilly Library Manuscript by Stephen Spender

Edited by Christoph Irmscher

Indiana U. Press. 160 pages, $34.66

IN AMERICA, at least, Stephen Spender (1909–1995) has had the ill fortune to be the least well known of that trio of British writers who rose to prominence in the 1930’s and whose works have lasted well into our own time. The other two were W. H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood, who not only settled in the U.S. but found the scope and openness of their new home to be so congenial that they first became fine American writers and then internationally acclaimed ones. The trio held fast for so long because they all had longevity, they remained close friends over the decades, and they were known to be gay, which during most of the 20th century meant having to stick together.

Spender’s Selected Poems of 1953, covering over two decades of his work, was proof of his importance in the U.S. and preceded by several years a similar collection of Auden’s work. Two years earlier he had published his autobiography World Within World, full of intimate portraits of Bloomsbury and other British literary circles, and actually pretty much anyone making a name at the time. The book wasn’t at all insular but included international names like Sartre, Gide, Neruda, and Malraux. A wonderfully readable work, it gained a new kind of fame years later when Spender sued novelist David Leavitt for copyright infringement in his novel While England Sleeps (1993), taking him to a British court that forced Leavitt to rewrite his novel (reissued in 1995). A new edition of World Within World came out in 1994.

Meanwhile, Spender was writing the kind of strong, beautiful, public poetry that perfectly captured his time and the concerns of his contemporaries. Being a communist, anti-industrialist, anti-Franco, and anti-Fascist, Spender was both politically and poetically correct. His personal glamour was aided by his family’s artistic centrality, by his never hidden homosexual affairs, and also by his heterosexual marriage to concert pianist Natasha Litvin, a desirable woman whom Raymond Chandler schemed for years to possess. His son, Matthew Spender, published a delicious memoir of the family’s general wackiness and multiple follies in A House in St. John’s Wood (2015). When the son confessed to the father that he was studying art and had a girlfriend, Stephen’s response was classic: “You’re a great disappointment to me on both counts.”

Meanwhile, Spender was writing the kind of strong, beautiful, public poetry that perfectly captured his time and the concerns of his contemporaries. Being a communist, anti-industrialist, anti-Franco, and anti-Fascist, Spender was both politically and poetically correct. His personal glamour was aided by his family’s artistic centrality, by his never hidden homosexual affairs, and also by his heterosexual marriage to concert pianist Natasha Litvin, a desirable woman whom Raymond Chandler schemed for years to possess. His son, Matthew Spender, published a delicious memoir of the family’s general wackiness and multiple follies in A House in St. John’s Wood (2015). When the son confessed to the father that he was studying art and had a girlfriend, Stephen’s response was classic: “You’re a great disappointment to me on both counts.”

The manuscript of Poems Written Abroad was unearthed not long ago in a Midwestern university library and is printed here for the first time. It dates from the summer of 1927, when Spender was a mere eighteen years old. It doesn’t have the stupendous weight of his best-known poems or even the clever fun of his prose works, but it is delightful on several other levels. Clearly it’s a notebook of someone who wants to be a poet, who must be a poet, and who is spending a summer on the Continent, teaching himself the trade.

From the first “Sonnet on Absence” of May 1st to the 26th poem of July 23rd, we can watch Spender grow as a writer by leaps and bounds. He tries out different forms—Petrarchan, Spenserian, and Shakespearean sonnets abound. He attempts styles as different as George Herbert and late Wordsworth. He writes prose as poetry and poetry as prose. His focus is all over the place. His control of his emotions is unsteady, at least at the beginning, but it tightens over time, as does his grip on the poetic line.

Suddenly we come upon his poem on the original Bluebeard, Gilles de Rais—hardly your everyday subject for a poem—which begins: “Gilles de Rais’/ face/ How blue the fringes shone!/ The tassels were/ torn from the air.” This is a step up from “Why shouldst thou mock my fingers. Churlish one so fair and so fair” or “I shall protest against this martyrdom” of only a month before. His long, pseudo-Tennysonian verse gives way to this “Clair de Lune”: “The moon has spilt/ Her milk/ In silver fountains/ Across the mountains—/ Until like silk/ It falls across my knee, the poet.”

Christoph Irmscher’s fourteen-page introduction, along with his bibliography and notes, tell you all you need to know about the manuscript’s history and its details. The book is oversized so as to show Spender’s ink drawings and original handwritten manuscripts facing the printed poems.

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).