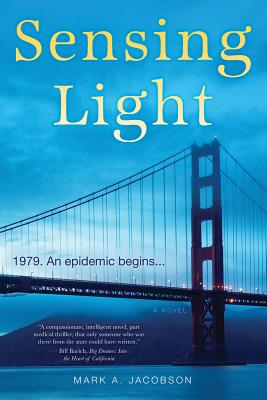

Sensing Light: A Novel

Sensing Light: A Novel

by Mark A. Jacobson

Ulysses Press. 288 pages, $15.95

FROM THE EARLY 1980s to the late 1990s, AIDS dominated gay life in America. Reports of a mysterious “cancer” spreading among gay men appeared in national publications in 1981. By the middle of the decade, sexually active gay men feared for their lives. Early arguments about closing gay bathhouses gave way to memorial services for dead friends, fundraisers to provide services for the sick, and political action to demand greater access to drugs and more funds for research to find a cure. When the AIDS Quilt came to our cities, we wandered among the panels searching for the friends we had lost. A major body of literature was produced in these years: plays, novels, short stories, and “witnessing narratives,” so that, in the memorable words of George Whitmore, a writer who died in 1989, future generations will know that “someone was here.”

For Americans in their thirties and younger, all of this is ancient history, which is why it is good to have Sensing Light, a novel written by a physician who first began working with AIDS patients in San Francisco in 1986.