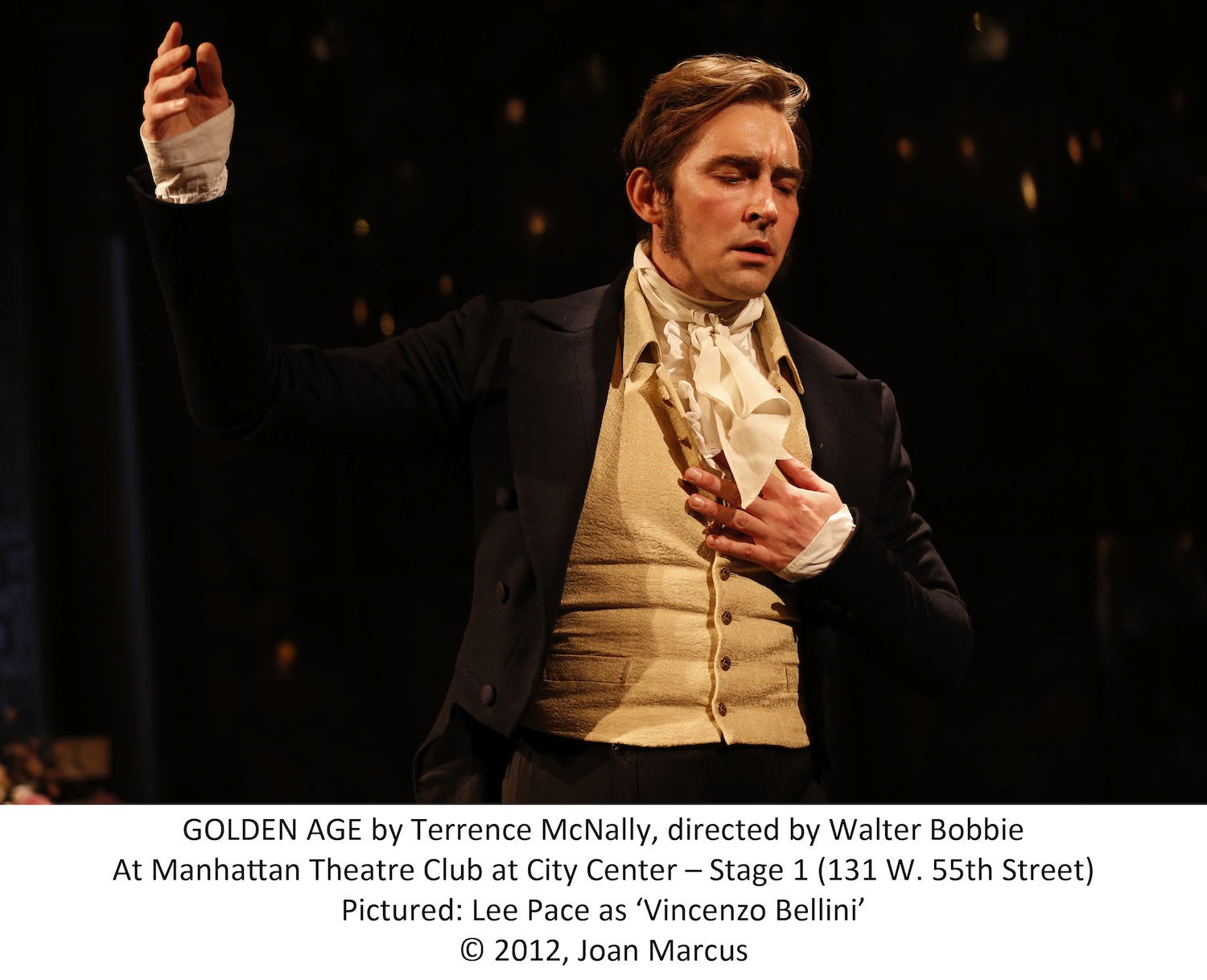

Golden Age

by Terrence McNally

Manhattan Theatre Club,

City Center Stage 1

Dec. 4, 2012–Jan. 27, 2013

POSSIBLY the most moving moment in Terrence McNally’s new play occurs when composer Vincenzo Bellini sits backstage listening to the premiere of what would prove to be his final opera, I Puritani. Overcome by the beauty of the music being performed on stage, he lapses suddenly into a daze and is oblivious to his lover, Francisco Floimio, with whom he has been arguing. Accustomed to Bellini’s mood swings, Florimo recalls in a dramatic monologue his waking one morning during their stay in a hotel on Lake Como to find an unkempt and nightshirt-clad Bellini seated at the piano, completing the composition now being played onstage, an aria that begins “Love brings me to your side in triumph and joy.” Although he aches to embrace his lover, Florimo refrains from doing so lest he disrupt Bellini’s reverie.