SCRATCH A DYKE of a certain age and you’ll get a bar story: funny, sad, sexy, and true. Perhaps there are not as many stories now as there used to be, what with so many lesbian bars in the U. S. disappearing. Or are they? Maybe they’re just changing.

Almost fifty years separate two lesbian bar projects, one from 1971 and one from 2020. Both projects document the presence and purpose of lesbian bars and narrate their stories. The Lesbian Bar Project was something I did as a student at Cal Arts in the early 1970s, and “The Lesbian Bar Project” documentary is a short film by Erica Rose and Elina Street that was released in 2020. For both Erica and for me, bars were pivotal in our coming out experience.

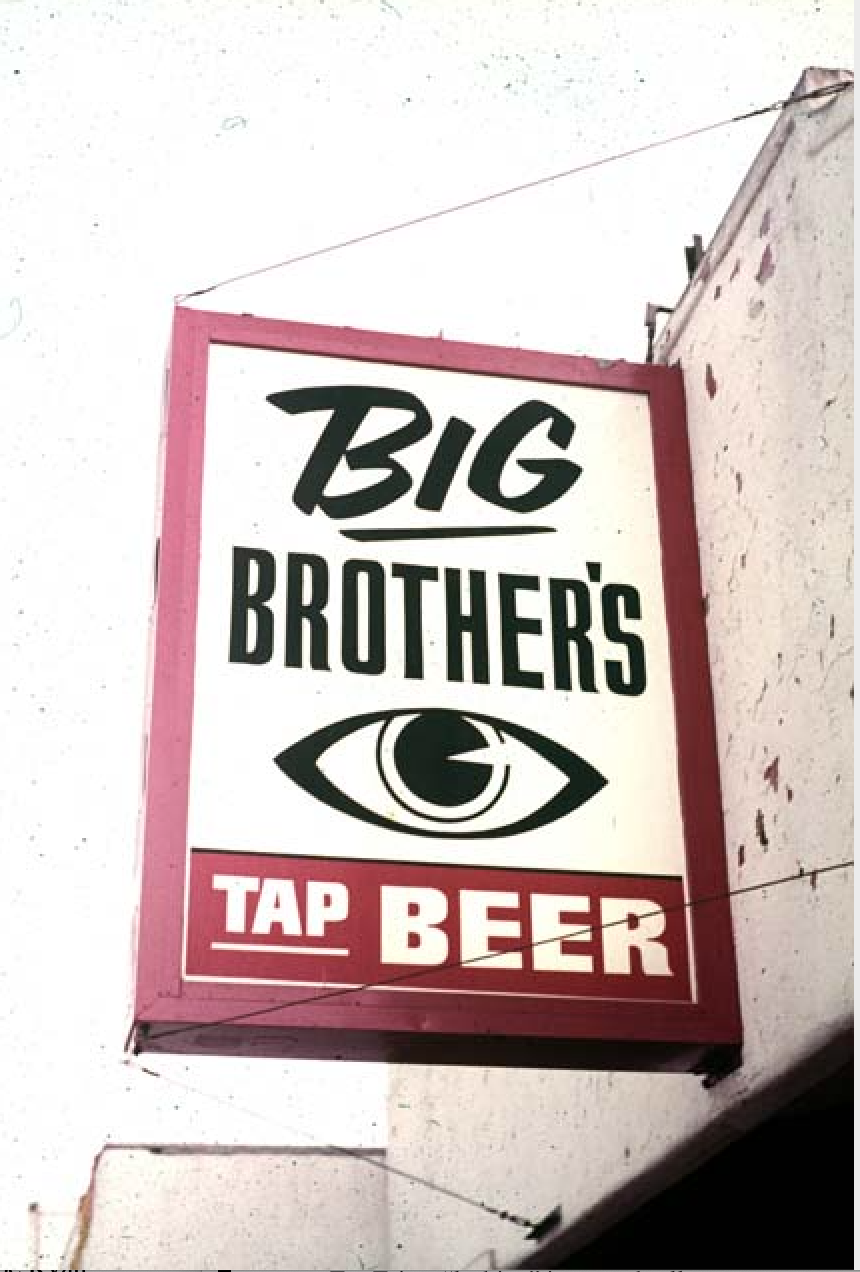

In 1971, I was a student in Judy Chicago’s and Mimi Schapiro’s Feminist Studio Workshop at Cal Arts in Los Angeles. We were assigned to explore something personal in any form we chose. I was new to L.A., and at 24 was just coming out. I had no idea where to meet lesbians until I discovered Big Brothers, my local lesbian bar in Venice. Dark, seedy, stinking of beer, it welcomed you with its candlelit red Formica tables and pool table in the back. I was thrilled, awed, intimidated, and excited to enter this space filled with women. Why not explore and document the lesbian bars of L.A. for my Workshop assignment?

In 2010, Erica Rose paraded into the Cubbyhole in New York City with some straight friends. They went to view the spectacle, but, once inside, Erica found herself exhilarated and excited in ways that she never expected. Totally drawn to it, she was not yet ready for it. That would come later, but what felt most compelling to her about being there was a sense of relief in being able to be her queer self in the company of her straight friends.

To my young lesbian eyes, bars were magical places where you could finally be yourself, openly desire and be desired, and do what you wanted without guilt or shame. In the early ’70s, just a few years after the Stonewall uprising, cops were no longer busting lesbian bars, and you would no longer be thrown in jail for wearing male attire, but the atmosphere for lesbians outside of the bars was still oppressive. To be identified as a lesbian could mean losing your job, your reputation, your family, and your future. A friend describes being a lesbian then as feeling that you were “the scum of the earth.” The bars may have been just a bigger closet, but they filled a crucial role. As long as everyone there was sworn to mutual secrecy, everyone was safe.

To my young lesbian eyes, bars were magical places where you could finally be yourself, openly desire and be desired, and do what you wanted without guilt or shame. In the early ’70s, just a few years after the Stonewall uprising, cops were no longer busting lesbian bars, and you would no longer be thrown in jail for wearing male attire, but the atmosphere for lesbians outside of the bars was still oppressive. To be identified as a lesbian could mean losing your job, your reputation, your family, and your future. A friend describes being a lesbian then as feeling that you were “the scum of the earth.” The bars may have been just a bigger closet, but they filled a crucial role. As long as everyone there was sworn to mutual secrecy, everyone was safe.

There were no lesbian bar guides, so finding out about the bars was by word of  mouth. I soon discovered there were many kinds of bars. There was the down-and-out Big Brothers,

mouth. I soon discovered there were many kinds of bars. There was the down-and-out Big Brothers,  to which I gravitated. Or take a bar such as the Hialeah House, which catered to a straight-passing crowd of secretaries, schoolteachers, and nurses, fresh from the beauty parlor, all dressed up in expensive clothes with big beehive hairdos. Joani Presents, located in the Valley, was a hoot. Joani, who had slicked-back platinum hair, was a drummer. Deliciously flamboyant, she set the tone for the place. She dressed her much younger girlfriend, a youthful version of herself, in a matching violet outfit. While Joani played the drums, the girlfriend sat at the end of the bar with a drink keeping watch. There was the story that Joani kept a shotgun under the bar in case of “trouble.” The Bacchanal and the Palms were spaces for dykes my age and a little older, and they were great places to dance. The Viking was another Valley bar.

to which I gravitated. Or take a bar such as the Hialeah House, which catered to a straight-passing crowd of secretaries, schoolteachers, and nurses, fresh from the beauty parlor, all dressed up in expensive clothes with big beehive hairdos. Joani Presents, located in the Valley, was a hoot. Joani, who had slicked-back platinum hair, was a drummer. Deliciously flamboyant, she set the tone for the place. She dressed her much younger girlfriend, a youthful version of herself, in a matching violet outfit. While Joani played the drums, the girlfriend sat at the end of the bar with a drink keeping watch. There was the story that Joani kept a shotgun under the bar in case of “trouble.” The Bacchanal and the Palms were spaces for dykes my age and a little older, and they were great places to dance. The Viking was another Valley bar.

To repeat: scratch a dyke of a certain age, and they will tell you a  bar story, usually a coming out story, or maybe a butch/femme story. Butch/femme was part of the cultural currency in which I came of age. There were nights at Big Brothers when it went all butch/femme. At those times, it was mainly a Hispanic crowd taking over: the femmes dolled up in frilly, sexy clothes, complicated hairdos, and lots of makeup, and the butches with high pompadoured, shiny hair, sharp suits, and boots with pointed toes. Strict adherence to these roles was common among some older dykes, but my friends and I did not indulge. We were just lesbians, maybe a little butch sometimes, maybe a little femme, but in no way stuck in a role.

bar story, usually a coming out story, or maybe a butch/femme story. Butch/femme was part of the cultural currency in which I came of age. There were nights at Big Brothers when it went all butch/femme. At those times, it was mainly a Hispanic crowd taking over: the femmes dolled up in frilly, sexy clothes, complicated hairdos, and lots of makeup, and the butches with high pompadoured, shiny hair, sharp suits, and boots with pointed toes. Strict adherence to these roles was common among some older dykes, but my friends and I did not indulge. We were just lesbians, maybe a little butch sometimes, maybe a little femme, but in no way stuck in a role.

A personal anecdote illustrates this situation—and also the need for secrecy. In the mid-’70s, two lesbian friends visiting family in Milwaukee encountered a woman friend of their mother, who whispered to them while mom was out of the room: “Do you want to go to a bar?” “Sure, yes,” they replied. “I am Spike the Dyke,” the woman announced, and then took them to her house, where she changed into butch clothes. It was dark and cold, and they got in her car and drove for miles and miles until they finally saw a red Schlitz sign blinking over a small building. That was it. They went inside, and it was jammed full of lesbians. A woman came up to one of my friends and said: “So, are you butch or femme?” My friend couldn’t answer, so the woman asked the other. She didn’t know what to say either. “Oh boy, you guys are so confused!” said the dyke, and walked away. No one hit on them all night because they couldn’t figure out what to do with them.

Lesbian bars played a pivotal role in both my own and Erica’s coming out. For my generation, they provided the only safe public place to identify as a lesbian; for Erica, forty years later, it also proved to be a haven. Even with liberal parents, both psychologists, Erica felt uncomfortable coming out to them even as recently as fifteen years ago. Although Erica did not come out until college, she began to feel attracted to other girls in high school. Her mother, supportive of Erica’s gay male friends, proved ambivalent toward Erica’s potential queerness. There was still a stigma attached to it. Erica felt this to be a gendered response, finding other lesbians whose mothers expressed similar discomfort at their coming out. But in a bar for the first time, she felt sexy and desired in the way that she had not known outside, where heteronormative standards still rule.

LESBIAN BARS have not prospered over the years. The Cubbyhole is the last of two lesbian bars in all of New York City. In the 1970s, in the city of Los Angeles alone, there were at least a dozen lesbian bars. And there were scores more across the country. In the 1980s, there were roughly 200 lesbian bars in the U.S. Today there are only 21 left.

The causes for this precipitous decline are manifold. In the fifty-plus years since the Stonewall Riots, same-sex marriage has become federal law and anti-discrimination statutes are widespread. Lesbianism has been mainstreamed. “The L Word,” flannel shirts, short hair—so many lesbian signifiers have been co-opted by the straight world. Bars are no longer necessary for coming out. Social media have blasted open the ways for lesbians to meet. You can come out now in grade school. In addition, the trans movement has upended lesbian life. Butch culture has nearly disappeared as many butch women have transitioned, causing them to give up their lesbian identity.

The pandemic alerted Rose and her co-director Elina Street to the alarming decline in the number of bars. Long before the pandemic, the bars had begun to feel old and uncool; only the party circuit mattered. But the pandemic accelerated the loss of these physical places of community and personal connection, and that is what prompted Rose and Street to produce their short documentary “The Lesbian Bar Project.” Their goal was to bring greater awareness of, and support for, the remaining lesbian bars across the country and to celebrate their history.

In October 2020, they released a Public Service Announcement and launched a fundraising campaign that helped raise over $117,000 for the remaining bars. In June 2021, they released their documentary and another fundraising campaign. The documentary spotlights the bar owners, community activists, and patrons in three cities—New York; Mobile, Alabama; and Washington, D.C.—and highlights their struggles during the pandemic and their hopes for the future. The 2021 fundraising campaign raised over $150,000 for the bars. The executive producer for both the PSA and the film is Lea DeLaria. Rose and Street are currently developing a documentary series expansion of “The Lesbian Bar Project” set to premiere this year.

For the future of lesbian bars, we need to consider how language has changed. The word “lesbian” has evolved as gender has come to be seen as more fluid. It was once defined as a cis woman who desires other cis women, but that definition now seems too narrow. For Erica, “lesbian” is an umbrella term embracing a number of marginalized groups, including transmen, transwomen, bisexuals, non-binaries, “theys,” as well as lesbians as traditionally defined. As the meaning of “lesbian” has evolved, so too has the purpose and meaning of lesbian bars. Erica is convinced that the bars will survive as long as they adapt to the needs of today’s generation and absorb the language of the times.

With the disappearance of bars comes the loss of their physical space and the community of women being up close with others like themselves. Erica foresees a future in which bars are transformed into community centers open to a wide range of marginalized people. Open all day, serving food, they would respond to whatever people need. In the 1970s, a bar was a place where a lesbian could come on Friday to cash her weekly paycheck. Today’s bars might be able to address other mundane needs. Erica sees a political future for the lesbian bar as well, as a place for organizing, advocating, campaigning, and strategizing. Bars are businesses, and survival often depends on partners. Today’s partnerships involve an expanded community that can include straight people and gay men who have the resources to make it work. Erica points to a number of bars opening up in Queens, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. She has a very hopeful vision.

The stories lesbians tell of the bars of the 1950s are replete with sexy secrecy. My East Hampton neighbor, Mary Jane Meaker, aka lesbian writer Ann Aldrich, regales me with New York City tales of hooking up with Patricia Highsmith and of getting another legendary lesbian writer, Ann Bannon, creator of Beebo Brinker, “horizontal.” But there was also the very real danger of police raids and nights in jail. Her stories differ from my own experiences in the 1970s, when bars were not dangerous in the same way. But they were revelatory and life-changing, putting me on my path as a lesbian as well as an artist and mural painter. Erica and her generation are creating new narratives for lesbians and lesbian bars, and in this way, the bars will survive.

What I see as a loss of lesbian culture she describes as a shift in that culture. Gone are the days when you went into a bar and were asked if you were butch or femme. There was a sexy thrill inherent in the clandestine nature of those bars, but nostalgia can be dangerous. The oppression that necessitated the bars as safe havens was treacherous, engendering shame, suicidal self-loathing, and fear. What we were seeking was relief, love, community, and a sense of our history as lesbians. The survival of lesbian bars depends upon their adapting and evolving, hopefully leading to a host of more lesbian bar stories.

Christina Schlesinger, artist, writer, activist, and cofounder of SARCinA, lives and works in New York City and East Hampton, NY.

Erica Rose is a film producer and director whose latest film is the documentary short “The Lesbian Bar Project.”

Discussion2 Comments

Glad to learn the dancing was great.

I had graduated High School in 71′. I knew from a young age I was attracted to “girls”. Living very close to “Big Brothers”, (actually right down the street !) I gained the courage to pass through the doors, Summer of 72′. There, sitting on the bar stools were women dressed as men and women extremely overdone as women. Silence hung in the air immediately upon my arrival. I was asked by a “butch” if I was butch or fem. I was so confused, a lump sat in my throat. I was then called a “diaper dyke” and told to leave. As I sat in my car I felt completely alone. If these were lesbians, what am I? I finished nursing school, moved to Sonoma County and Guerneville became my home for the next 25 years. In those 25 years I watched and participated as my town became the resort escape, into the Redwoods, from SF. Christina, Thank You so very much for your documented journey. Out of the Bars and Under the Stars became and continues to be the mantra when the doors began closing