HERVÉ GUIBERT, Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories

HERVÉ GUIBERT, Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories

Edited and translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman

Semiotext(e)/MIT Press

269 pages, $17.95

IN 1989, as his energy was increasingly sapped by his rapidly multiplying AIDS-related health problems, novelist Hervé Guibert debated not simply making public his HIV status but doing so in a devilishly subversive way. He targeted a particularly gossipy magazine editor, to whom he sent a manuscript that made passing reference to his altered health condition, knowing that this would set the news of his illness racing “around town—under the seal of secrecy—like wildfire.” He understood full well that associates would probably shun him out of fear of being exposed to the virus, and that once editors had reason to doubt his ability to meet deadlines, he would risk losing the portion of his income that he earned as a freelance journalist.

And yet, as Guibert noted in the version of the event published in To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, he faced “calmly and with a kind of indifference” the prospect of the revelation of his most important secret, “because it was only natural to betray my secrets, since I’d always done that in all my books, even though this genie could never again be stuffed back into its bottle, and I would never again be a part of the human community.” The only real indecision that he faced at the time was whether to continue on a debilitating course of AZT, which could buy him just enough time to complete what would become his powerful trilogy of novels about his AIDS treatments (To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, Compassion Protocol, and Man in the Red Hat), or whether he should commit “suicide, to keep from writing … those dreadful books.”

Guibert’s end-of-life dilemma encapsulates his entire writing career. Closely identified with what critics have termed “autofiction” or the roman faux (“false novel”), Guibert wrote narratives that are narrowly based on the circumstances of his own life, in which he reveals not only his own secrets but those of his friends. Immediately upon publication, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life was passionately denounced not only for having outed influential philosopher and literary theorist Michel Foucault, but also for having revealed Foucault’s predilection for raunchy sex in the back rooms of San Francisco’s leather bars in the 1970s and early ’80s. As part of the latter project, he supplied a haunting description of Foucault’s final days.

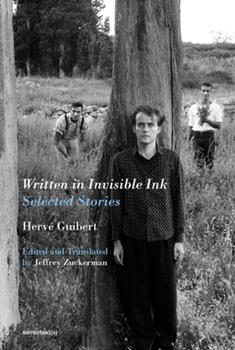

Also a noted photographer [see cover image], Guibert’s compulsion to uncover and deliver the truth as he saw it to the maximum extent possible meant that he wrote “dreadful books,” in his words, books that it pained him to write and, he hoped, that would pain his readers to read. To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life remains one of the most devastating narratives to issue from the AIDS epidemic, in large part because of the willingness of its protagonist, “Hervé Guibert,” to record the most blasé details of his daily routine as he faces a maddening and totally irrational form of annihilation. Yet by forcing him to look unflinchingly at the dark void at the heart of human existence, AIDS elevated both the author and the character Hervé Guibert to a level of tragic heroism that places him in the tradition with Œdipus, Lear, and Hamlet, as he not only suffers but also contemplates the source of his pain.

Consequently, Guibert occupies a privileged place in the development of gay narrative with respect to the choice given an artist between maintaining a cautious silence, practicing crafty dissimulation, or proclaiming the truth about their sexuality. Simply put, how openly could gay men of earlier generations write about their experience without having to disguise it in some way to make it more acceptable to a hypercritical book-buying public? W. H. Auden rationalized that Shakespeare carefully avoided using gender pronouns in sonnets like “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day?” (which is spoken by a mature man to his younger male lover) in order to pre-empt alienating his politically powerful and primarily heterosexual readers. Similarly, feeling unable to write openly about his obsession with his chauffeur Alfred, Marcel Proust transformed the latter into “Albertine” in Remembrance of Things Past. Elsewhere in Proust’s novel, the supposedly heterosexual narrator (who, like the author, is named Marcel) witnesses various incidents of same-sex sexual activity, but always from a distance, thereby providing the reader with tantalizing hints of same-sex behavior even as the narrator’s (and author’s) fig leaf of heterosexuality remains securely in place.

Christopher Isherwood, conversely, asserted himself to be “a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking,” as he wrote with unprecedented frankness about himself and his relationships in the third person in narratives from The Berlin Stories in the late 1930s to Christopher and His Friends in the mid-’70s. Like Isherwood, Guibert—who, as it happens, was also a professional photographer—functioned as a camera, delivering frank images of disturbing realities, often in a voice that was unsettlingly dispassionate. This descriptiveness proved a politically radical act in his AIDS narratives, in particular Cytomegalovirus, in which he forces readers to gaze upon his AIDS-ravaged body, refusing them the comfort of a polite distance.

Guibert’s lifelong impulse to tell his personal truth, however dreadful, drives the short stories that span his short career. These are the works that have been selected and translated for Hervé Guibert, Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories. Writes translator Jeffrey Zuckerman in his preface to the book:

Guibert’s particular stance toward other men—that is, open, unashamed, yet not brazen homosexuality—was not meant as a provocation. It was, however, a quietly revolutionary stance in line with his particular brand of rebelliousness, in which, to quote a line from the end of Ghost Image, “secrets have to circulate.” If homosexuality was one such secret, Guibert refused to keep it, whether in his life or in his art.

Guibert’s particular stance toward other men—that is, open, unashamed, yet not brazen homosexuality—was not meant as a provocation. It was, however, a quietly revolutionary stance in line with his particular brand of rebelliousness, in which, to quote a line from the end of Ghost Image, “secrets have to circulate.” If homosexuality was one such secret, Guibert refused to keep it, whether in his life or in his art.

Consider the opening movement of Propaganda Death, a collection of récits written while Guibert was a teenager but only published after his death: “My body, due to the effects of lust or pain, has entered a state of theatricality, of climax, that I would like to reproduce in any manner possible: by photo, by video, by audio recording.” The narrator is dispassionately interested in the drama of all his body’s activities, “eructations, defecations, ejaculate from jerking off, diarrhea, phlegm, oral and anal catarrhs of the mouth and ass.”

It is his determination to record what is hidden in the depths of the body, a portion of which is revealed only during the “theatrical” activities of sexual climax and physical suffering, that drives him to seek new and entirely unconventional methods of recording those inaccessible realities. Thus, if it were possible, he would [p]osition a microphone inside my mouth, filled as with a cock, as far down my throat as possible, in case I have an episode: contractions, brutal ejaculations or defecations of shit, groans. Position another microphone inside my ass, for it to be drowned in my tides, or dangled over the toilet bowl. Alternate the two noises, mixing them: stomach groans, throat groans. Record my vomiting, rooted in the opposite extreme of orgasm.

Here the narrator is determined to find a means by which “this contorted, flickering, screaming body [may]speak,” and in such a manner as the body may reveal its complete self and not only those parts of the self that are permissible to display socially. As the phallic image of the microphone invading his throat and rectum suggests, the very act of writing is itself a form of sexual congress or of physical communion with the world.

An unsettling depth lies beneath the objective rendering of surface realities in these stories. In “Personal Effects,” for example, the contents of a traveler’s toiletries kit are described in such clinical detail that they might initially be entries in an extraordinarily detailed police inventory or the description of items in an industrial sales catalog. But the very uses to which one puts a comb, Q-tip, nose wipe, or cuticle trimmer suggests those interior processes by which the body expels dead cells as hair or fingernails, or gestates phlegm. Thus, no matter how carefully one maintains one’s physical appearance, there are always processes operating beneath the surface that will wreak havoc on one’s grooming.

Conversely, in “The Sting of Love,” a complex emotional trauma is described as though it were an actual physiological event like the ingestion of bitter-tasting food or the corrosion of the skin by acid. And in the late story, “A Man’s Secrets,” a medical scan of the lesions on Hervé’s own brain is both a metaphor for the troubling realities that lie beneath a seemingly unperturbed surface and the occasion for an explosion of associations regarding memories stored in the brain that no CAT scan can ever reveal. The brain, traditionally thought to be the seat of reason and the antithesis of genital pleasure, is shown to be essential to the generation of both sexual pleasure and devastating grief.

Taking the title of the collection from one of the stories included in the volume, Zuckerman notes that Guibert’s stories aim at suggesting experiences that, like powerful memories, continue to resonate with a person even as they fade into insubstantiality, “like a treasure lost in the depths.” However, as Zuckerman reminds the reader, the French phrase for the “invisible ink” in which one of Guibert’s narrators says that his story has been written is “encre sympathique.” The adjective sympathique connotes “not secrecy and subterfuge,” as when invisible ink is employed in spy thrillers, “but kindness and closeness.” Somehow Guibert makes tender the dreadful truths—about AIDS, physical realities, and emotional traumas—that he forces his reader to acknowledge.

Raymond-Jean Frontain’s edition of Terrence McNally’s Muse of Fire: Reflections on Theatreis forthcoming from Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.