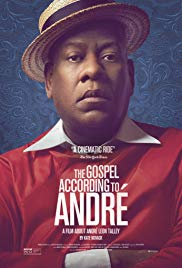

THIS YEAR promises a bumper crop of film documentaries. Already released are films on Grace Jones, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Fred Rogers, and Pope Francis, to name a few. That motley list is made all the more unusual by the addition of The Gospel According to André, which narrates the life and career of socialite and fashion journalist André Leon Talley. Talley was introduced to the national stage in another fashion documentary over twenty years ago, Unzipped (1995), which profiled the designer Isaac Mizrahi. Talley is virtually the only black man in that film. He also appeared in The September Issue (2009), which used the occasion of Vogue magazine’s annual supersized issue to probe the life of its austere editor, Anna Wintour. There too, Talley is a large and garrulous presence in a picture full of unsmiling white people. In the quarter century covered by these three films, very little seems to have changed in terms of industry diversity. Of a queer black man who stands 6’6” and wears ornate caftans to accommodate his massive figure, it seems odd to say that he has flown under the radar. But in life and in pictures, he has known only the supporting role until now.

Talley was born in 1949 in Washington, D.C. His parents left him to be raised by his grandmother in Durham, North Carolina. She supported them by cleaning dormitories at Duke University. Despite their lesser economic station, her employment there gave young André license to visit Duke’s libraries, where he discovered Vogue. In the film, Talley recounts that the Duke students threw rocks at him as he passed by the preppies. While that hostility is unsurprising for the era, it could have been much worse. The first black student did not enroll there until 1967, and the battle over segregated spaces embroiled Durham as he availed himself of one of the largest libraries in the South. Talley acknowledges the turmoil of the era, but its relationship to his life remains unclear.

Talley was an undergraduate at North Carolina Central University, about which little is said in the film. He went on to earn a scholarship to graduate school in French studies at Brown, and the more liberal world of New England began to solidify his determination for audacious self-expression, though here the film raises more question than it answers. It includes interview clips with a close childhood friend, and the viewer can hear the friend’s sluggish southern drawl and easily forget that, in theory, the two men should sound exactly alike. But Talley’s speech sounds aristocratic. The film offers footage of Talley’s social circle at the Rhode Island School of Design, with pictures of house parties and flamboyant dress-up games, and again the viewer can almost forget that Talley attended Brown, not RISD. The film’s silence on these inconsistencies is maddening.

An internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art enabled a career-defining encounter with influential fashion editor Diana Vreeland, who tapped Talley to be her personal assistant. His career

ascended steeply from there, as he took a series of coveted positions, including one as an editor at Warhol’s Interview magazine, before landing at Vogue. His life in New York in the 1970s brought him into contact with the darlings of Manhattan nightlife, many of whom did not survive the era. AIDS is another of this film’s silences, but Talley opens up, just a sliver, about the fact that he seldom dated and never had a serious romantic relationship. He confesses to wishing that he had met the right person, and another interviewee connects Talley’s abstinence with his upbringing in the Southern black church.

Talley’s flair, his fluent French, and his intellectual acumen combined at the beginning of his career to foster his rapid ascent. Fran Lebowitz recalls in the film that her mother believed Talley to be an African prince. Talley himself recalls that when he first interviewed Karl Lagerfeld, the designer immediately took him to his bedroom and festooned him with clothes from Lagerfeld’s own wardrobe. But upon reaching his forties, Talley was no longer svelte, and the film addresses his obesity without pushing too hard. Any film focusing on a black man’s relationships to white women is going to have to address their bodies sooner or later, and Talley’s body has always stood strikingly apart from his industry peers. This is where the film is arguably at its best if also its briefest. To say that even a documentary needs an antagonist is likely overstating things just a little, and it is absolutely refreshing to see a film take more interest in a black man’s abilities and creativity than in his conflicts with white people. But Talley’s struggle to overcome his racial and sexual difference is unarguably central to his story, and the film thrives when we glimpse some of his battle scars.

By the halfway point in the documentary, one has to wonder whose film this really is. Kate Novak, whose producer credits include the well-received films Page One: Inside the New York Times (2011) and Ivory Tower (2014), is the director. But she seems fearful of losing the cooperation of her subject. In promotional appearances for its release, Talley described his experience with the documentary as feeling like open-heart surgery. In one unguarded moment, Talley’s experiences with white hostility come rushing out. But in another segment, he’s shown ordering a camera crew to “just get me walking,” and the film mostly returns to feeling like a feature-length selfie.

The aforementioned fashion documentaries Unzipped and The September Issue had the strength of a clear framing device, the production of one fashion collection or one issue of the magazine. This one ping-pongs a bit from this premise to that, even using the 2016 presidential election as a backdrop before losing interest in that. Talley’s return visits to Durham are by far the more interesting narrative framework for this story. Talley shows a restrained wistfulness when visiting the place his grandmother last called home, which he said he bought and decorated as an homage to Vreeland while retaining the touches his grandmother would find familiar. The small but sumptuously appointed home, which Talley preserved as she left it, is the only sign that his grandmother lived to see the success he became, and clearly reflects his taste more than hers. Talley sits in her living room and reflects on her death while swaddled in heavy garments seemingly suited for a winter’s night on his own porch in upstate New York. Anna Wintour comments that she thinks of Talley’s lavish garb as the armor he needs to face the world, an oddly frank moment from a woman at the top of a commercial empire built on romantic illusions. The film is understandably less interested in laying waste to the industry than in extolling Talley’s place within it. And even in the absence of greater coherence or more probing inquiry, this film never fully loses its way. Talley has led a remarkable life, and the film casts a wide net to trap as many fascinating pieces of it as it can.

J. Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer in English and media studies at Bentley University.