“I wanna go places, I wanna do some things

I wanna be a star, I wanna have a big name.”

— Ike and Tina Turner, “Make Me Over”

ON JUNE 16, 2015, the newly resigned president of the Spokane, Washington, chapter of the naacp came out on national television. But what she came out as remains unclear. She told The Today Show’s Matt Lauer, “I identify as black.” Given that both of her parents identify as white, many viewed Rachel Dolezal’s story as a delusion. Others cited the example of Bruce Jenner, who had announced to the world only weeks before that he identified as a woman. They argued (at times sarcastically) that if “Caitlyn” Jenner could change her gender, why couldn’t Dolezal change her race? At the heart of this jab lay a suspicion that neither woman’s claim was authentic. Coincidentally or not, a slight young man named Dylann Roof entered a historic black church in South Carolina the very next night and killed nine people in an effort to begin a race war. As disparate as these stories are, they all critique—or even preserve, depending on one’s reading of them—the fundamental principle that there is such a thing as a “true self,” and that race and gender are irrevocable, defining components of that self.

Early American literature is an intriguing study in conflicting views on this matter. The Transcendentalist writers tended to endorse a view of the physical world as being at once sacred and distracting. The purpose of literature and other spiritual practices was to quiet the din of one’s environment and allow the “eternal” self to emerge. Thoreau’s Walden experience, Emerson’s view of poetry, and Whitman’s “song” of the self are all variations on this idea: the self is an already made expression of Divine or “original energy.”

Frederick Douglass, while relying on similar conventions in his own narratives and speeches, was more specific on the link between class ascension and personhood. It comes as no surprise that a man who was property in the eyes of the state would speak with greater clarity on how the myth of authentic self-making was tied to the politics of race, class, and even masculinity. In his classroom lectures, the late Cornell professor Joel Porte often cited an anecdote in Douglass’ 1845 narrative in which Douglass taught himself to read by working in a shipyard. The writer somewhat tediously recounts learning the letters F, A, L, and S from pieces of timber marked for “starboard” or “larboard” placement, “fore” or “aft.” Porte perceived in that painstaking passage the anagram fals slf, or “false self.” Slavery was a false self that Douglass could shrug off through personal struggle and triumph over external definitions and social restrictions, an autobiographical topos that persists in African-American literature to this day.

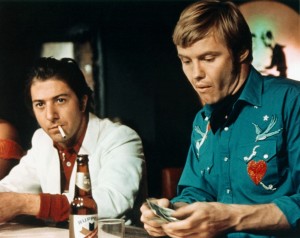

Two acclaimed American films critique this myth of self-making specifically through the lens of gayness: John Schlesin-ger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1997). Both films focus on itinerant men who use migration as an occasion to reinvent themselves entirely. The pinnacle of their transformation occurs through erotic but chaste

relationships with other men. The films remain at best ambivalent about the notion of self-invention, implying instead that male-male desire is a core element of identity that cannot be suppressed or reformed. These films also link expressions of desire to issues of class, suggesting that while gayness may be ubiquitous in society, it exists in a social context that exerts varying levels of cultural repression and state control. While the upper classes may not be totally immune to the effects of such repression, wealth tends to provide individuals with the capacity to create social enclaves that shield them from its worst consequences.

Midnight Cowboy was released one month before the Stone-wall Riots, receiving an X rating from the Motion Picture Association of America. In a 2001 article (Journal of Science and Society), “Closing the Heterosexual Frontiers: Midnight Cowboy as National Allegory,” Kevin Floyd observed:

What was viewed in 1969 as the strong sexual content of Midnight Cowboy—its homosexual content in particular—is generally understood as the main reason for its X rating. … But the Academy’s response to Midnight Cowboy was symptomatic not only of national concerns about “permissiveness”—national phobias about male homosexuality in particular—but also of profound ambivalence about the status of the Western genre during the Vietnam era.

What sent tremors through American masculinity in Floyd’s account was the dual shock of homosexuality and the failed war hero. But the Motion Picture Academy clearly responded positively to the film’s daring subject when it garnered the Oscar for Best Picture. And it remains to this day the only movie with a gay or even a sexually ambivalent protagonist to have won that award, though Philadelphia, Brokeback Mountain, and The Imitation Game were nominated.

Midnight Cowboy opens with a kind of conceptual establishing shot, the parking lot at the Big Tex Drive-In Theater. This locale establishes the site of the naive hero’s imagination: the theater is implied to be where Joe Buck (Jon Voight) derived the fantasy of becoming a cowboy. In the shots that follow, we see Joe putting on his cowboy suit and packing to leave. Everything in Joe’s life apparently fits into a single suitcase, including a poster of Paul Newman, also dressed as a cowboy. Beyond telegraphing Joe’s cinematically-derived cowboy fantasy, this poster also speaks to Joe’s sexuality. In the documentary The Celluloid Closet (1995), screenwriter Stewart Stern comments on his film Rebel Without a Cause (1955) that “we know the Sal Mineo character is gay largely because he has a picture of Alan Ladd in his locker.” So Joe’s poster begs the transitive question: does Joe want to be Paul Newman or to be with him? Either choice requires that Joe strive to be someone in New York that he cannot be in Texas.

Before Joe boards the bus, he says goodbye to just one person, a diminutive man who washes dishes in the diner where Joe is a busboy. Having little else to stick around for, Joe becomes a “bus” boy of a different sort, boarding the Greyhound to New York with nothing and no one awaiting him there except the imagined women he believes he can conquer and grow fat on financially. Like so many before and after him, Joe’s pilgrimage to New York enacts a Bildungsroman quest for wealth, acclaim, and above all a clean break with an inferior birthright.

David Carter’s Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (2004) and Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010) are just two of many nonfiction accounts of how minority populations in particular have fled to New York for just such a chance at a new life. What they were fleeing from included poverty, Southern violence, family disownership, sexual persecution, and much more. Before leaving Texas, Joe confides to the man in the diner that the men in New York are “mostly tutti fruities,” as if life in the city were inherently softer than the rugged terrain of rural Texas. But the idea that he himself might be a “fruit” appears not to have occurred to him. The irony that Joe must leave Texas to become a cowboy is compounded by the irony that New York is far more Darwinian than Texas, and Joe is not up to its challenges. He spends roughly the first quarter of the film getting taken advantage of, spending money rather than earning it, even after he reluctantly turns from female tricks to male ones. His fortunes do not change until he forms a bond with one of the people who conned him, a homeless, decrepit man named Enrico Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman). Rico, or “Ratso,” as he is derisively called, has all the street cunning that Joe lacks. With Rico’s aid, Joe gradually does find his way toward a viable clientele, the bored women of the Upper East Side who apparently are as lacking in virile companionship as Joe imagined.

On his way to that success, almost imperceptibly, Joe and Rico grow closer. When the condemned building in which they’re squatting is invaded by the city, they roam the streets aimlessly, just trying to survive. Gradually, as is often the case in buddy films, one buddy is growing and changing while the other, stuck in his old ways, is destined not to make it. Joe absorbs Rico’s cunning and gains independence while Rico, dying apparently of tuberculosis, can no longer even walk. In one of the most startling moments in the film amid Rico’s last foray into the city streets, the two men are standing outside a loft before entering a party to which Joe is invited and which Rico is crashing. Joe examines Rico and recognizes his decay: “You’re sweating all over the damn place.” As he lifts the bottom of his shirt to mop Rico’s brow, Rico leans into Joe’s bare torso and wraps his arms around him. This hungry embrace is as close to consummation as their relationship will ever get. But Joe ultimately abandons his “midnight cowboy” lifestyle just as he is finally making a success of it because Rico’s condition has grown desperate. Joe gives up the fantasy cowboy role to be the man that Rico needs him to be.

The men experience a certain amount of intimacy, physical and otherwise, but it has its limits. The omniscient point of view of the film allows us to see in their dreams what they never disclose to each other. Rico dreams of frolicking on sunny beaches next to a shirtless Joe who, despite his athleticism, struggles to keep up. Joe, meanwhile, has recurring nightmares about a woman in his past, “Crazy Annie,” a sexual foil through whom Joe seems desperate to prove his own virility. His flashback nightmares tell inconsistent stories, suggesting that Texas held some trauma that he cannot admit even to himself. In one version of the dreams, Annie is gang raped and points an accusing finger at Joe. In another, Joe himself is raped by the same group of men. Far from being a tabula rasa like the drive-in screen, Joe is presented as a palimpsest bearing ineffable traces of a queer sensibility to which he surrenders fully when (we must imagine) he carries an invalid Rico in his arms onto a bus bound for Miami. When Rico dies before they reach Miami, a distraught Joe bravely wraps his arms around Rico and stares back defiantly when others on the bus turn to gawk at them. That is all we know of the man Joe has become, and all we need to know.

Midnight Cowboy constantly invites us to consider the relationship between the actual and the aspirational self. Very little of what Joe once aspired to be isn’t traceable to someone he is emulating. Fear of mimicry is surely why American culture guards so ferociously, on and off the screen, its perimeters around what we can imagine. The Celluloid Closet has shown how homosexual characters in film reluctantly progressed from the role of antagonist to the role of antagonized. Often giving in to sentimentality and even fatalism, the film industry eventually let go of gay sex as a lethal perversion and moved toward depicting it as the victim of a culture that refused to let authentic gay selfhood survive. In short, gay characters “progressed” from killing those around them to killing themselves.

ALTHOUGH The Talented Mr. Ripley revives that well-worn trope of the homicidal gay man, it seeks to undermine our suppositions about how (or whether) identities, sexual and otherwise, are constructed, evaluated, and authenticated. Life seems to ricochet Tom Ripley (Matt Damon) through a series of mistaken identities, all of which he tries on for size, simply because they’re better than his current reality of poverty and loneliness. His identity changes occur primarily through encounters with a wealthy, jaded social class that deludes itself as much as it’s deluded by Tom. The core injustice of the film is that, even as a poseur, Tom is truer to himself than the rich hypocrites whose world he infiltrates.

Tom’s story begins at a cocktail party, where a shipping magnate mistakes him for the Princeton classmate of his son, Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law). The patriarch wants to pay Tom to go to Europe to retrieve the prodigal son. The filmmaker crosscuts the genteel cocktail party with scenes from Tom’s real life, his squalid apartment and his demeaning job as an attendant in the toilet at the symphony. The symphony montage underscores the idea of Tom as someone who craves a better, artistically richer (not merely a financially richer) life. Though developing this dichotomy is a complex affair, writer-director Anthony Minghella seems interested throughout the film in portraying Tom as a thwarted artist who’s interested in money only as an entrée to cultural experiences. The leeway for decadence here is still quite broad; yet Tom’s intense passion for artistic indulgences seems to set him on a higher philosophical plane than many of his wealthy peers.

Tom’s effort to persuade Dickie to heed his father’s wishes plays out as an attempt to seduce him by pretending to have identical taste in art and music. Tom’s performance of identity goes through three main stages. His first persona is constructed to incur the approval of Dickie. The second is the æsthetic self that flourishes only when sustained by the Greenleaf fortune. The third, the one he invents spontaneously in Naples, is the stage of pretending to be Dickie after having killed him, a crime of passion that occurs when Dickie finally rejects Tom’s romantic overtures. The only thing separating the second and third selves is that Tom-playing-Dickie must also play heterosexual. While Dickie courts the attention of several men, he never relinquishes the pretense of heterosexuality. Inheriting Dickie’s life thus means inheriting his baggage.

In point of fact, in embracing Tom as the protagonist of the film rather than the villain, the audience is forced to reckon with the question of whether Tom is somehow entitled to Dickie’s identity. For one thing, he’s so good at it, so adept at playing Dickie, who was in many ways inept at playing himself. If the audience does decide that Tom deserves to retain the role of Dickie, it can only do so by accepting the moral compromises that Tom himself struggles to accept, including going unpunished for Dickie’s murder.

Upon his first sighting of Dickie, Tom already seems to be imagining himself as this man. Practicing with an Italian vocabulary book and looking at Dickie through binoculars, he recites, “Questo e la mia faccia. … This is my face.” Here, the film echoes Midnight Cowboy’s dual fantasy of Paul Newman as both role model and love object. In the next scene, as he schemes to convince Dickie of his fabricated Princeton life, he becomes painfully aware of his separation from Dickie’s world. Tom looks nothing like anyone on this Riviera, which is covered with bodies bronzer than his own. Tom’s whiteness ironically marks him as marginalized from a leisure class that can spend all day in the sun.

Tom nonetheless befriends Dickie on the transparently false premise that they met at Princeton. Their first conversation about the senior Greenleaf begins with Dickie’s offhand comment that everyone should have one talent. When Dickie asks Tom what his talent is, Tom responds, “Forging signatures. Telling lies. Impersonating practically everybody.” To demonstrate this, Tom delivers an impersonation of Mr. Greenleaf with menacing precision. Coupled with his other demonstrations of craftiness, the film is leading the audience to the ironic conclusion that perhaps Tom is never more himself than when he is attempting to represent someone else, but the film takes a threatening tone when this theme emerges.

This again raises the question: Who is Tom, exactly? Tom Ripley, a work of fiction in the literary sense, often seems willing to regard himself as a work in progress in the metaphorical sense, such that all aspects of personality are simply waiting for the occasion to be invented. Cynthia Fuchs notes that the film “treats [Tom’s] self-reinvention not solely as pathology (surely, this is clear enough) but as a desperate and understandable effort to achieve the class/sex/race mobilities that he sees all around him. Montages of his romantic club-hopping with Dickie make the point: White boys play black, straight boys play gay, the moneyed boys play whatever they want.” So, which passions are authentically Tom’s own, and which are crafted for the benefit of some audience? The film further teases the tension between real and assumed identities through a flirtatious conversation in which Dickie wears and then removes Tom’s glasses as Tom compares him to Clark Kent. In this same conversation, Tom declares that nothing is more naked than a man’s handwriting, and that Dickie’s writing reveals a “secret pain.” The comparison to the handsome comic book hero lays bare Tom’s desire for Dickie while also likening Dickie to a character who lives in secrecy. The analogy outs Tom and closets Dickie in one stroke.

The film’s core irony is that Tom’s imposter role is emotionally authentic; not to adopt it would be to live a lie. Minghella doesn’t fully sever ties to his source material, the Patricia Highsmith character whose external changes are linked to no such higher truth, making him into a soulless—and therefore boundless—predator. Contrary to the ideal of the self-made man with all his limitations, the social chameleon is seen as a menace for his ability to be “self-made” on too great a scale and with too much ease. Resembling the homicidal socialites Andrew Cunanan and Clark Rockefeller in this way, Tom’s crimes in Highsmith’s novel erupt from the lack of moral grounding that would have come from tethering the self to an essence that is not only economically confined but morally so.

Toni Morrison famously quipped that Bill Clinton was our “first black president,” oddly foreshadowing Rachel Dolezal’s claim as president of the Spokane naacp. James Baldwin once wrote that “the value placed on the color of the skin is always and everywhere and forever a delusion.” Perhaps Dolezal is no more delusional for wanting to be black than anyone else is for wanting to prove her wrong, for believing there is anything at stake in the question that our folly hasn’t placed there. Robert Frost wrote, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” but walls are part of the architecture of the human psyche and an integral part of how we find our way through the social maze.

Tom Ripley and Joe Buck may be dramatically different on a superficial level. Joe is escaping to New York; Tom is escaping from it. Joe aspires to make himself over in the image of a rugged frontiersman who, even in Manhattan, is an aloof survivalist. Tom aspires to be part of a community of æsthetes who go to the opera, the symphony, the places where men conquer ideas rather than landscapes. But these men’s stories suggest the same theme, that there actually is such a thing as human rebirth, that it is possible for people to transform their own lives in profound ways. But that transformation is bound by forces from without, chief among them class privilege, and forces from within, notably romantic love. Those forces work together to create the experiences that we are destined to have, and to shape human character in ways over which personal whim has almost no control. In such circumstances, fortune plays the greatest role.

Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer in English and media studies at Bentley University.