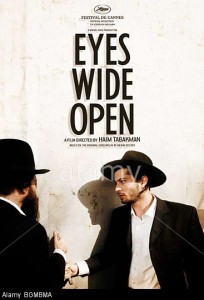

Eyes Wide Open

Directed by Haim Tabakman

Original screenplay by Merav Doster

Distributed by Here Films

EYES WIDE OPEN is a compressed drama of forbidden same-sex love within an insular community, namely the highly regulated society of Orthodox Jewry in a tight-knit neighborhood in Jerusalem. Presented in New York at this year’s Jewish Film Festival, the film is a stark reminder that the irregular contours of gay experience are perhaps best depicted by those outside the commercial cinema who are not bound by its cosmetic imperatives.

Eyes tells the tale of Aaron, a kosher butcher who at film’s start is taking over his father’s shop after the elder man has died. Soon a young, darkly handsome yeshiva student, Ezri, arrives on the scene in a downpour, asking to borrow Aaron’s phone in order to call a friend. We only hear Ezri’s half of the conversation, just enough to clue us in to the young man’s predicament: