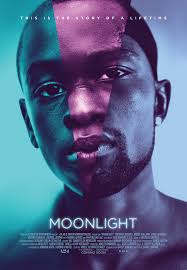

Moonlight

Moonlight

Directed by Barry Jenkins

A24 and Plan B Entertainment

THE HELP (2011), Twelve Years a Slave (2013), Selma (2014), Loving (2016)—movies about slavery and segregation have replaced historical biopics like Ali (2001) and Ray (2004) as the main means for the film industry to tithe to the church of “diversity.” In truth, the oppression genre is frequently little more than a way to tell white epiphany stories using nonwhite garnish. In this light, perhaps the biggest accomplishment of Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight is that the filmmaker seems to be talking about his own, African-American world. The film captures such social ills as poverty, drugs, coming out, bullying, and incarceration, but the characters are real people rather than social problems.

Jenkins’ film is a triptych, telling the story of the protagonist through three distinct stages from late childhood to young adulthood. This film’s episodic structure harks back to Richard Linklater’s Boyhood (2014). Lacking Linklater’s capacity to invest twelve years into his shooting schedule, Jenkins opts for the more traditional approach of hiring multiple actors to play the main character as he ages: Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes. The trio’s physical differences are significant enough that the audience must wait for visual confirmation that each new actor is still playing the same person. Even the protagonist’s name changes from one act to the next. Names, like human identity itself, prove to be a negotiation between what a man proclaims about himself and what the people in his life perceive in him or push him to be.

The hero’s first philosophical “pusher” really is one, a drug dealer with a softer heart than his life’s trade would suggest. Juan (Mahershala Ali) shelters the young “Little” from some street toughs in the opening scene, but he finds it impossible to get the kid to reveal his name, his address, or anything else of value. Juan’s girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe, the film’s best-known star) has only slightly better luck getting him to open up. It seems that the young man, whose real name we eventually discover is Chiron, has reason to avoid going home, which turns out to be his drug-addicted mother, Paula. His mother vacillates wildly between overweening protectiveness and the desperate belligerence of an addict craving her next high. When the reticent Chiron does communicate, it is typically through actions rather than words, and it only takes a few of these to change utterly the course of his life.

Life is not all turmoil for Chiron. Just as Juan had plucked him from the wilderness of the streets, a schoolmate named Kevin (also played by three actors) pulls him from the slings and arrows of the playground. Juan had taken Chiron to the beaches near their Miami home and taught him how to swim, an apt metaphor for the lifesaving role that Juan would play. Later, Kevin takes Chiron to a beach at night, into the “moonlight” of the film’s title, and introduces him to the world of gay sex. Kevin seems to be everything that Chiron is not: confident, insouciant, self-aware—and masculine. Both boys, it turns out, are gay; but masculinity is an adaptation that one boy has achieved, the other not.

Arguably, masculinity in its various forms is the main antagonist in this film. One of the most difficult aspects of being gay is the way in which one’s sexuality can telegraph itself against one’s will, even before puberty. For Chiron, it’s a secret that his silence cannot contain. Here, Moonlight becomes a “passing” narrative like Tea and Sympathy (1956), Imitation of Life (1959), or Paris Is Burning (1990). When we meet Chiron in the last stage of the narrative, he has built his body into a compensatory muscular vision, like the sculpted armor of Christopher Nolan’s Batman. We sense that Chiron has rehearsed the gestures of masculinity every day of his life with a barbell in his hand.

A decade has passed, and Kevin reappears, after having betrayed Chiron in his own attempt to pass as straight, a move that put an end to their budding adolescent romance. The two men are soon back to their boyhood selves, suggesting that the human personality has an authentic core that it never fully escapes or conceals. Rhodes’ diverting performance (as grown-up Chiron) skillfully plays off the expressions of the two earlier incarnations to knit this patchwork role together, especially when Chiron’s past suddenly returns. He has moved to Atlanta now, but when the ghosts of Miami follow him there, he reverts back to the lanky kid in need of male tenderness, affection, and shelter.

Chiron confides to Kevin that he has had no physical contact with anyone since their encounter all those years ago—straining plausibility a bit, since the sight of his shirtless body caused the audience to gasp audibly when I saw the film. That said, the majesty of this quiet story can be found in the gazes that Kevin and Chiron exchange amid the harsh realities of their young lives. For an industry still licking its wounds after charges of racism, Hollywood could do worse than to recognize the unique contributions of this enchanting film.

Ken Stuckey is a senior lecturer at Bentley University.