IT WAS VULGAR & IT WAS BEAUTIFUL

IT WAS VULGAR & IT WAS BEAUTIFUL

How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic

by Jack Lowery

Bold Type Books. 432 pages, $35.

OF LATE, compelling first-person narratives have detailed ACT UP New York’s inchoate years of the late 1980s—notably Sarah Schulman’s Let The Record Show and Peter Staley’s Never Silent—when AIDS activists battled government, pharmaceutical, and religious malfeasance. Flamboyant street actions caught the attention of the media, and artists enlivened the theatricality of these protests. Artistic affinity groups met weekly to create galvanizing agitprop imagery and video documentation. Gran Fury, DIVA TV, and Testing the Limits were some of the art collectives that emerged.

Jack Lowery’s It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful examines the legacy of one of these groups, Gran Fury, self-defined as “a band of individuals united in anger and committed to exploit the power of art to end the AIDS crisis.” Their æsthetic appropriated Madison Avenue style advertising, blurring the lines between graphic art and activism, handing out Xeroxed flyers with singular slogans at rallies or pasting posters onto public spaces in late-night, guerilla-style handiwork.

This recognition was complicated. While sponsorship allowed the group to create larger-scale works, at times language had to be modified, and some members thought it was diluting their political propaganda focus. Outrage demanding public actions seemed muted on gallery walls. As some members began to focus on their own careers, others burned out from the ongoing annihilation of the pandemic, leading to the group’s gradual dissolution.

Lowery tells the story of Gran Fury by drawing from interviews and archival material from ten of its members, and by delving into the ACT UP Oral History Archives organized by Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman. The group got its unofficial start when a curator at New York City’s New Museum, Bill Olander, asked ACT UP to create a window installation in 1987 that incorporated Silence = Death iconography and images of such homo-hating political figures as Jesse Helms, Jerry Falwell, William F. Buckley, and Ronald Reagan.

Well over fifty people worked on this installation, which received enormous media coverage. Filmmaker Tom Kalin spoke about participating: “In making Let the Record Show, a bunch of crotchety and opinionated people found a way to work together. And it made us all feel less scared.” With the success of this project, the ad hoc group wanted to continue working together and formally chose the name Gran Fury (after the Plymouth car model used by New York Police). The collective was originally open to all and was quite porous. Eventually the group limited membership for efficiency and productivity.

Lowery’s incisive book functions as a catalogue raisonné of the collective’s œuvre over the eight years of its existence, including fully realized agitprop images and messaging alongside failed or less successful pieces. The latter are understandable, as graphic material was oftentimes quickly produced for planned street actions, sometimes the night before, and images were constantly repurposed. The title of the book comes from an interview with collective member Donald Moffett, a visual artist: “What made ACT UP so effective? … It was vulgar and it was beautiful.”

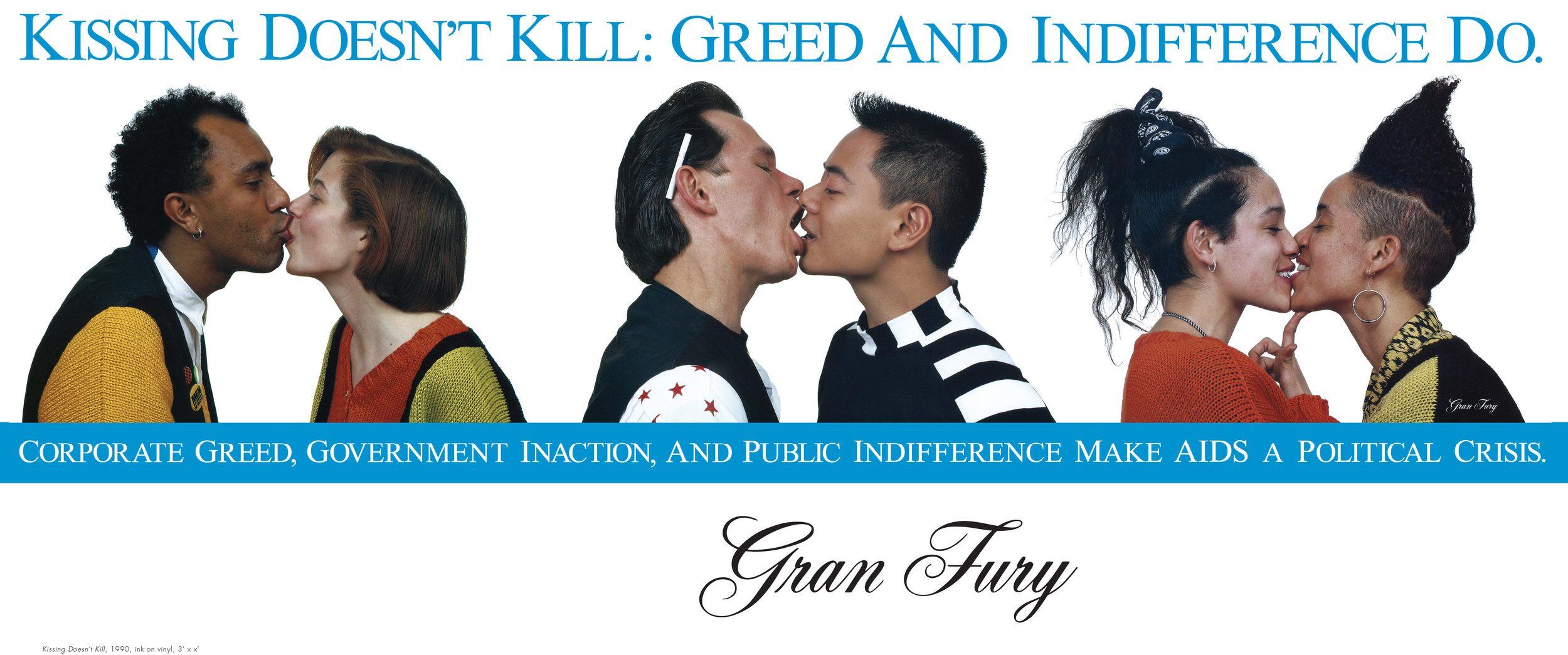

Highlights include the back stories on some iconic images, including Read My Lips showing two sailors kissing, created for a “kiss-in,” and the Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do poster that ran on buses and subway platforms featuring multiracial couples designed to mimic a highly stylized fashion ad. Their bloody handprint graphic was recycled in many iterations to remind leaders: “You’ve Got Blood on Your Hands.” Gran Fury also designed fake currency dropped onto the trading floor during an ACT UP protest at the New York Stock Exchange, and they tucked their own New York Crimes four-page insert into newspaper vending machines throughout Manhattan to protest the media’s inadequate reporting. In one poster, they reminded the art world that Art Is Not Enough.

Highlights include the back stories on some iconic images, including Read My Lips showing two sailors kissing, created for a “kiss-in,” and the Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do poster that ran on buses and subway platforms featuring multiracial couples designed to mimic a highly stylized fashion ad. Their bloody handprint graphic was recycled in many iterations to remind leaders: “You’ve Got Blood on Your Hands.” Gran Fury also designed fake currency dropped onto the trading floor during an ACT UP protest at the New York Stock Exchange, and they tucked their own New York Crimes four-page insert into newspaper vending machines throughout Manhattan to protest the media’s inadequate reporting. In one poster, they reminded the art world that Art Is Not Enough.

Invited to exhibit at the prestigious Venice Biennale, Giovanni Carandente, its closeted director, tried to block their two large panels, The Pope and the Penis, attacking the Catholic Church’s opposition to clean needles and condoms and reprising two of their most popular slogans: “Men: Use Condoms or Beat It” and “AIDS Kills Women,” with an image of an erect penis between them. However, he was not successful in preventing their display at the exhibition.

Invited to exhibit at the prestigious Venice Biennale, Giovanni Carandente, its closeted director, tried to block their two large panels, The Pope and the Penis, attacking the Catholic Church’s opposition to clean needles and condoms and reprising two of their most popular slogans: “Men: Use Condoms or Beat It” and “AIDS Kills Women,” with an image of an erect penis between them. However, he was not successful in preventing their display at the exhibition.

Gran Fury’s final poster was elegiac. Four Questions was printed in small black type against a large gray background. One of the designers, Loring McAlpin, said this was not a call to action, but a poster “for ACT UP, the Lower East Side, and gay men in New York. We were talking to ourselves.” The four questions were taken from member Mark Simpson’s notebooks: “Do you resent people with AIDS? Do you trust HIV-negatives? Have you given up hope for a cure? When was the last time you cried?”

It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful makes a compelling case for the significance of Gran Fury’s imagery to the efficacy of ACT UP. Lowery also sees a larger significance: “Maybe the most important lessons from Grand Fury aren’t about AIDS explicitly, or even about pandemics, but rather the ability for this kind of work to sway public opinion, to shape our attitudes, and to change our worldviews.”

John R. Killacky, a longtime contributor to this magazine, is currently serving in the Vermont House of Representatives.