We Were Here

Co-directed and edited by Bill Weber

Produced and directed by David Weissman

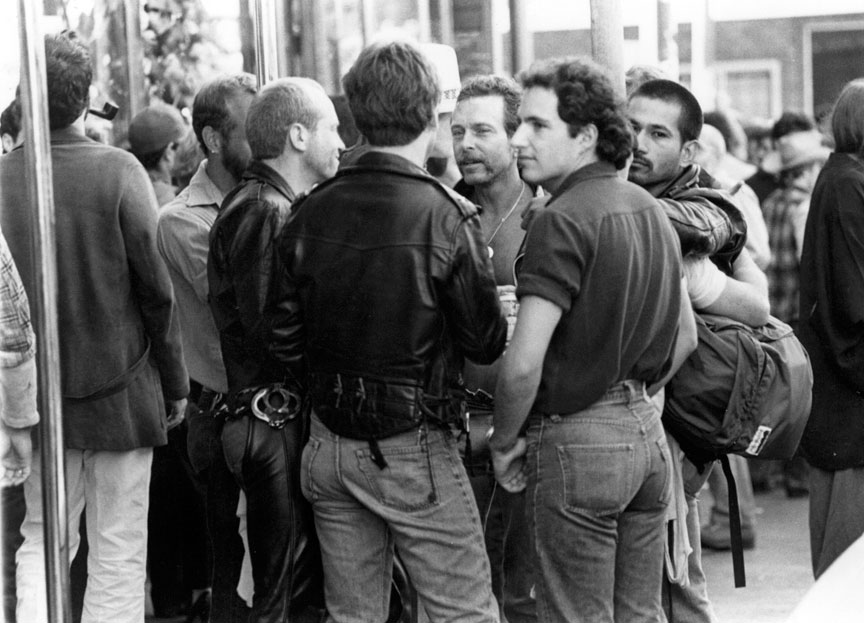

THE OPENING PORTION of We Were Here, David Weissman and Bill Weber’s new documentary about the early years of AIDS in San Francisco, is one of surprising humor, even celebration. Using on-screen recollections of the film’s interview subjects interspersed with archival photography and snippets of the era’s popular music, the film reminds us of the creative energy and sexual exuberance that thrived in San Francisco, particularly in the Castro neighborhood, in the mid-to-late 1970’s. And this upbeat opening is reprised in the film’s wonderfully affirmative conclusion. Between these end points, however, is a sad and sobering look at the ruthlessness with which AIDS ravaged the city’s gay community.

The two directors last teamed up for The Cockettes, their 2002 documentary about the San Francisco drag-queen-hippie theatre troupe of the late 60’s and early 70’s. Their current subject seems far removed from that film, and We Were Here certainly wrestles unflinchingly with a dark chapter of gay history. But its dominant themes are hope, survival, and renewal.