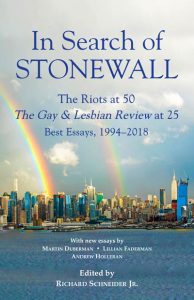

This year marks The Gay & Lesbian Review‘s 25th anniversary, and to commemorate this milestone we’ve published In Search of Stonewall, a collection of articles selected from our first 136 issues, since 1994. Starting today and every week in January, we’ll be highlighting sections of the book. Below is the first installment, historian Martin Duberman’s introduction to Part One: “Flashpoint: New York City, June 1969.”

WRITING gay history is no less perilous than writing any other kind. “Objectivity” is the professional historian’s golden calf, but as we know, that prized possession proved elusive—a false idol. Historians necessarily base their accounts on the always fragmentary, partial evidence that happens to have come down to us from the past.

WRITING gay history is no less perilous than writing any other kind. “Objectivity” is the professional historian’s golden calf, but as we know, that prized possession proved elusive—a false idol. Historians necessarily base their accounts on the always fragmentary, partial evidence that happens to have come down to us from the past.

The inescapable limitations of historians themselves—the idiosyncratic experiences and values they often unconsciously hold—inevitably shape their interpretations, further distorting our ability to know “what actually happened.” If postmodernism has taught us anything, it is that subjectivity is omnipresent in historical narration. No matter how scrupulous the historian is, the evidence will always remain incomplete, the portrait tainted—and historians themselves will always, inescapably, interpret the past through the distorting lens of their own times and preoccupations. “Objectivity” remains the ideal goal, but like all ideals it can only be approximated, never achieved.

Thus it is with regard to the events at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. The vast majority of those who directly participated in the rioting, or observed it from the sidelines, have never been asked for or offered their versions of what took place. Among the small minority who have borne public witness, accounts vary—sometimes crucially.

One persistent view credits a butch dyke with striking the first blow; another insists on awarding the garland to a drag queen; a third assigns it to one of the street kids who hung out in the park adjacent to the bar. One “authoritative” account has it that the cross-dressing rebel Sylvia Rivera first threw down the gauntlet; another counters that Sylvia was never even present at the riots. A prominent theory about the corrupt Sixth Precinct’s uncharacteristic failure to alert Stonewall’s Mafia owners to the imminent raid ascribes it to the owners’ tardiness in the making their usual payoff. An opposing theory emphasizes instead that the Precinct’s new commanding officer was sending a message that henceforth the payoffs had to be higher—or, argues yet another theory, that he was determined to abolish them altogether. And so it goes.

The six commentators who describe the events at Stonewall in the following section make honorable attempts at completeness, and none directly contradicts well-established outlines of the rioting. Yet each chooses to highlight aspects of the event that—for whatever subliminal reasons—best suit their subjective snapshot. In turn, I myself am drawn—for reasons no less subjective or unwitting—to favor certain emphases in one account over another. Thus I prefer the way Michael Denneny references the 1960s context in which the Stonewall riots took place—and particularly the Women’s Movement—to the way in which David Carter minimizes the importance of the pre-Stonewall homophile movement, insufficiently acknowledging the extraordinary bravery of that tiny, intrepid band in publicly protesting their odious treatment.

Finally, though, I’m most taken with Toby Marotta’s central emphasis on Stonewall as “a disorganized rebellion against oppression,” yet one that “triggered a chain reaction of community-building and political organizing that was emulated across the country and publicized throughout the world.” Understanding that, I’d agree, is more important than knowing whether the first or the third night of the rebellion was the bloodiest—or whether Sylvia was or was not sleeping off a hangover.

October 2018

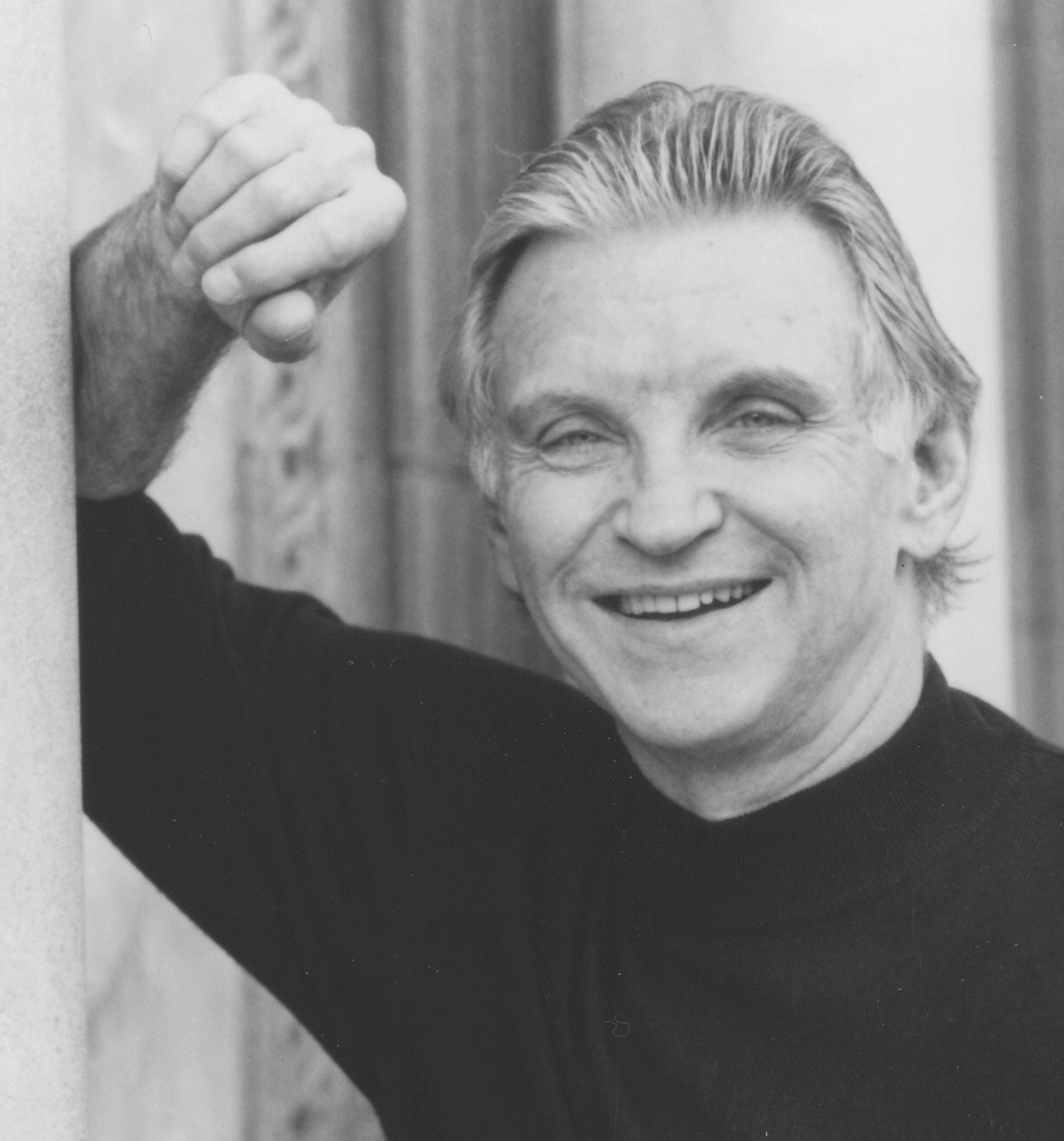

Martin Duberman is the author of Stonewall (1994), The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein (2007), and Luminous Traitor: The Just and Daring Life of Roger Casement (2018), among many other books. Founder of the Center for Gay and Lesbian Studies at CUNY, he was professor of history at Lehman College for many years.

Martin Duberman is the author of Stonewall (1994), The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein (2007), and Luminous Traitor: The Just and Daring Life of Roger Casement (2018), among many other books. Founder of the Center for Gay and Lesbian Studies at CUNY, he was professor of history at Lehman College for many years.